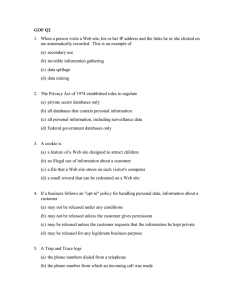

government and corporative internet surveillance

advertisement