Lolo Creek Resource Assessment (2004)

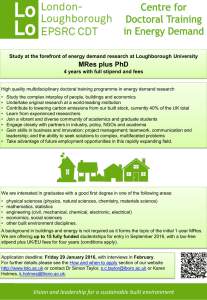

advertisement