learning to sail

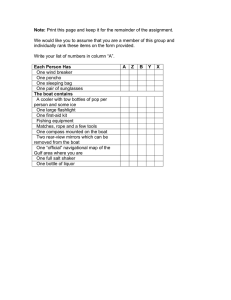

advertisement