by John Orrelle - American Museum Of Fly Fishing

advertisement

A

The

F l .Fisher

Ephemera

Ephemera: any thing short-lived

or transitory-such as mayflies

of the order Ephemeroptera. In

a museum collection the term

refers to paper materials, usually

printed items other than books.

I n our case, tacklecatalogs, scrapbooks, fishing licenses, fishing regulations, angling-related advertisements,

business cards, and the like, would qualify. These are items that generally get

thrown out when the desk drawer or the

attic trunk is purged of ostensible junk.

We often forget the importance of the

ephemera and focus o n the more glamorous items: rods, reels, and flies. We cannot overemphasize the importance of the

ephemera to a museum. As an example,

consider the scrapbook of C. F. Orvis that

we mentioned in a previous edition of the

American Fly Fisher, which is in our collection. It is a veritable gold minr o f

information concerning the early days of

the Orvis Company. Bills, receipts, business cards, and advertising material contained therein allow one to construct a

vivid picture of the workings of o n e o f

America's most important early tacklemakers. Without the scrapbook, this

information would have been lost to us.

So when you spring-clean next, if you

find something related to angling (related even in the remotest way), don't throw

it out-send it to

us, please. Let us

decide if it is

really junk.

. , ,.

F ~Fisher

v

WINTER

'I'RI IS'I'EES

P;tuI Rulingvt

Nil k I.yr,ll*

1a11I).Mac kxy

I.er\,i* M . HOI<I<.II 111

A n < o ~li3 1 c ~ ~ k \

J:arnm E M,(:lotncl

i.

R o l r . ~R.

~ H ~ ~ ~ L n ~ ; l r t v l \2'. I l : ~ r i v , n M ~ . l ~ lM.D

D ; I ~ (>III~I~II.sII

H<,I, Milt ht.11

ROY D. (:II:~>~II

11.

C:ilrl ,\. N;IP;IIB(. J r .

<:hl i \ t o p l i r ~(:<~,k

Mic li;~cI0 w r . n

1.c1gIi 11, I'vtkin\

C:li:~rlc\ R . l i < l ~ < , l

101111 F.II\I~~<,

R o m i I1r.lkin*

G. 1 ) ~ kb ' ~ ~ i l : ~ y

'I'IIc.o~IoI~.

Kogowhki

1%'.M i < l i i ~ rI l: i ~ ~ g c ~ ; t l ~ l

St.111 Ko\vnl~:tum

Ar~lit.

~I;

r I<IC~

K c i ~ l Ru\\cll

i

I\,;sn Sc h1011. M.1).

( k ~ r ( l t i c I..

~ (;I;IIII

I':IILI

S<l~~tllctv

Ric l i i ~ r cI

l I;IIIIIII\I.~

kt ~IV\I St l i ! v i c l ~I~

S i l r i i ~ ~(:.

c l JOIBIIU)I~

Htrli K~IIIII

SIC~IIC~II SI<B:~II

l'vtvr \\'. SIIOI

M ; ~ r l i tJ.~ KI,:BIC,

Hc,!~nc,llH. I l p \ o r ~

R i c t ~ ,:I ~I:.

~K r w

R. 1'. \'i~n (;IIVI(.IIIXY.L

M r I KI~CRVI

I)<,,,

l.:,I1l,,.

~ 1 1 , l \1;1,1 I,c,;,,

S;u~i\';I~INrs,

1);wicI 13. l . c < l l i ~

D I k\rm

~

I..

Wliilnc)

Ellio! 1.iski1i

EIIW;II

(;. X ~ I I I

OFFICERS

Ctrnirmati 01 ttir Board

C;ardnrr L. Grant

Pr?.iidrnl

Rol)rrt R. Ruckmaster

Ifirr Prrsidrt~l

W. Mic-liarl Firqrr;rld

Trrniu rrr

Leigh H . Perkins

Srcrrtary

Ian D. Mac-kay

A.rsi.slanl Srcrrlary lClrrk

Charles R. Eirhel

STAFF

Exrruliz~eDirrclor

John Merwin

1)rpuly I)irrrlor/Dn~rlopntrnl

Lyman S. Foss

Ex~ruliz~

Assiilanl

r

Pailla Wyman

Rr,qi.ilmr

Alanna Fisher

Journal Edilor

David B. Ledlick

Arl Dirrrlor

Martha Poole Mcrwir~

Copy Edilor

Diana M. Mor1c.y

OJJrrl I'rrpamlion and Prinling

Lane Press. Burlingron. Vermont

Volume 13 Number 1

1986

O n the corler:

Photograph of John Harrington Keene from the frontispiece of

the 1921 edition of his book, The Mystery o f Handwriting.

We belime that the photograph was taken circa 1888, when

Keene was thirty-three years old.

Automatic Fly Reels

John Orrelle

............... 2

Dry Flies on the Ondawa: The Tragic

Tale of John Harrington Keene

.

David B. Ledlie

......

18

............

23

Pyramid Lake and its Cutthroat Trout

Robert J. Behn ke

William Radcliffe and the

Grand Mesa Lake Feud

William Wiltzius

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Notes and Comment

Museum News

. . . . . . . .8

Automatic Fly Reels

Ralph A ldrich's outrageous

fishing float, patented in 1885

by John Orrelle

We are pleased to welcome back

to the pages of the American Fly

I Fisher, reel-expert J o h n Orrelle.

John's last contribution appeared

more than ten years ago in the

first volume of the American Fly

Fisher (1974).H i s article o n automatic fly reels is a chapter from his forthcoming book o n American fly reels. W e

hope to publish additional chapters i n

future issues of our journal.

T h e period in America from after the

Civil War to the close of the nineteenth

century was one of rapid industrialism,

one in which machines sprouted and proliferated like some strange crop from an

alien planet. There were machines for

everything-the more complicated the

better; whether or not they worked was

sometimes an entirely peripheral matter.

Few people were immune to the fascination and allure of all this gadgetry, which

promised to do jobs faster and cheaper (if

not better), and whose siren call often

trapped otherwise sensible people into a

dinosauric bog of financial ruin. Among

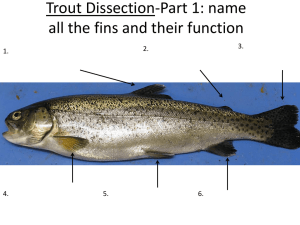

Arthrr Wakemarl pntrntrd h z ~lznrtwlrlznq rla11ce zn 1881. It nlloulrd

thr anqler to rotntr h z ~

fly or bazt

and thur naake zt trrm morr lzfrlzkr

to thr fzth.

fitv4'

others, one recalls the quixotic pursuit of

Mark Twain for a type-setting machine,

an automated marvel that never worked

and in whose quest he unsuccessfully

squandered several fortunes.

It was during this same period that

some of the wildest fishing tackle imaginable made its way i n t o the patent

records, from spring-loaded fish hooks

and traps, to hinged fishing rods (with

built-in scales), tandem reels, and oystero p e n i n g machines. O n e of the more

imaginative of these was the brainchild

of L. A. Peck of Newton, Massachusetts,

w h o i n November 1876, patented a

machine for fishing that was described in

the 0fficial Gazette simply as ". . . a n

apparatus for throwing a weighted hook

and line a distance seaward." Judging by

the patent drawings, the inventor must

have had in mind the outer limits of the

Grand Banks, for the machine looks fully

capable of throwing a line across Lake

Superior! Constructed in the form of a

catapult, the patent records fail to mention if a model was submitted-in which

case a team of horses would have been

required to transport it.

But there were other equally ambitious

inventions. Two of my favorites were the

c o n t r a p t i o n s of R a l p h Aldrich a n d

Archer Wakeman, whose genius is certainly evident, if not somewhat mis,guided.

T h e Aldrich patent (see illustration)

deserves top honors. When I first came

across it, I thought I'd made a mistake,

for right in the middle of the section of

fishing floats and reels (from a Commissioner's Report, 1885)was what appeared

to be a New England fishing dory. A

quick reading of the patent text revealed

this to be indeed a fishing float, although

it was really a self-contained, fully automated fishing machine. Constructed of a

piece of wood about a foot to a foot and a

half in length, the float was fashioned in

the shape of a boat, featuring an anchor, a

folding mast w i t h sail (whose significance was paramount), and a fishing reel

installed amidships. T o use the float, the

hook was baited, a length of line drawn

from the reel, and the mast locked in a

horizontal position by a tripping bar attached to the reel:

In this condition the float is to be

anchored out in the water and the

hook dropped. T h e mast and reel

will remain in this locked condition until the line is disturbed sufficiently by the biting of a fish to

turn the reel, whereupon the crank

will be moved off from the rod h

and set the reel and mast free. thus

giving play-line to the fish andsignaling the biting or catching of a

fish.

But it is the last paragraph of the patent claims that contains the prescriptive

zeal of Mr. Aldrich; with a certain entrepreneurial elan, he advises as follows:

In most cases the fisherman will

provide himself with seueral of the

floats, and after anchoring them

out in the water will await the

hoisting of a sail, upon which he

will proceed to the float, pull in the

fish and rebait the hook and reset

the float, and in most cases the bott o m of the floats will be painted

green, so that when i n the water

they will resemble the leaf of some

water-plant and not frighten the

fish (!). [italics mine]

Archer Wakeman's invention (see illustration) was just as incredible, especially

when one realizes that its sole purpose

was to twist line! His "fishing tackle,"

doubtless classified by a shocked patent

clerk hesitant to call it anything more

specific, is best appreciated by reading

the actual patent description, which in

delicate circumlocution minimizes the

problems of line twist:

A divice to be applied to a fishing-line for the purpose of twirling

or rotating the line, and with it the

fly or bait at its end. Arotary diskor

head to which the line or gimp is

attached is connected with a crank,

or with an automatically operating

mechanism by which the line may

be rotated.. .. T h e line B, or much

thereof as extends from the reel to

and through the tubular guide, is

made of gimp, or of other material

having sufficient stiffness to turn

without buckling o r twisting to

any material extent, yet capable of

being readily wound upon the reel.

T h e line being provided with the

usual fly or bait, and the latter

being allowed to hang from the rod

and thereby to straighten the line,

it will be seen that rotation imparted to the shell or cylinder by the

train E will be transmitted to the

line B, and through it to the bait or

fly, the swivel of the bait being

made sufficiently tight to prevent

rotation therein u n t i l a fish is

hooked, a n d resistance thereby

offered to the rotation of the bait.

There were numerous other madcap

schemes for catching fish or "improving" tackle, and while the above examples are somewhat removed from flyfishing (excepting the Wakeman patent,

which at least is picturedwith a fly on the

line), they capture the spirit of the times

very well.

It was out of this atmosphere and the

preoccupation with machinery that the

automatic fly reel was born. Particularly

well suited to those whose sole objective

was to catch more and bigger fish faster,

they typify the pragmatic bent of the

period and the inordinate concern with

efficiency. Of the criticism sometimes

leveled at these reels, it is significant that

this usually centered on their mechanical

aspects, occasionally its heavy weight,

but rarely if ever on theappearance of the

reel. Thus, however pedestrian in form,

automatic reels were symbolic of the

American's love of gadgets, and were destined to become immensely popular.

YAWMAN & ERBE REELS

T h e earliest automatic fly reels successfully marketed in this country were the Y

& E reels, manufactured by the Yawman

& Erbe C o m p a n y of Rochester, New

York. Although inscribed with a patent

date of December 9, 1880, the actual patent record for this reel gives a date of

December 7, 1880, which was issued in

the n a m e of Francis A. Loomis, the

inventor of the reel. O n July 5, 1881, a

second patent was issued, with no discernible change in the form of the reel,

but with one-half of the patent rights

assigned to James S. Plumb of Syracuse,

New York (what the relationship was

between Loomis and Plumb is anybody's

guess). Still later patents were issued on

February 28, 1888, and January 16, 1891,

with other patents pending at that time

(Note: many of the Y & E reels are erroneously stamped February 28, 1898 instead

of 1888). Most of these later patents

related to modifications of the braking

a r m , a l t h o u g h at least o n e of them

involved a new model of the reel.

There are two basic forms of the Y & E

automatic. Contrary to what the appearance of these forms suggests, the earliest

reel was not the one with the famous

winding key, but instead was similar to

the reel pictured at the left in the accompanying illustration. This is often confusing, since the model with the winding

key has such an antiquated look about it.

Early ads of the Y & E indicate that the

original form-the one that subsequently

was advertised as the Old Reliable-came

in one size only, but was made from a

choice of brass, nickeled brass, bronze, or

hard rubber. Shortly after its introduction (sometime in the mid- 1880s),the reel

was fitted with a n improved brakingand-release lever shaped in such a way as

to facilitate positioning of the finger in

the upturned end of thearm; earlier braking arms had been little more than a simple wire extension with a loop in theend.

T h e actual braking pad on the arm was

simply a wrapping of thread or other

line, which has a peculiar makeshift

appearance and is misleading to those

who have never seen a Y & E reel (the

immediate impression is that the linewas

wrapped around the arm as an emergency

measure, when in fact it was original

equipment, see illustration). It was the

modified braking arm (with the slight

crook in the end) that gave rise to the

Y & E slogan "The Little Finger Does It,"

which later appeared on the HorrocksIbbotson Utica Automatic.

Around 1890, two additional sizes were

added to the Old Reliable model series:

the no. 1, no. 2, and no. 3, that could carry

90, 150, and 300 feet of line respectively.

By this time, reels made from bronze and

brass had been discontinued, but the no. 1

and no. 2 reels werestill available in nickeled brass. hard rubber. and-for the first

time-aluminum; the no. 3 reel was

made from aluminum only. Thus, for

dating purposes, those reels made of

unplated brass or bronze are of a very

early vintage and naturally these are the

scarcest.. . .

By 1900 a new model had been introduced-the New Style Automatic Combination Reel, available in styles A, B, or C,

with plate diameters of 2 7/16, 3%,and 4%

inches. Stated line capacities were 125,

300. and 600 feet of no. 5 silk line (or 50,

90, and 150 feetwithout rewinding). This

New Style Reel featured a sliding plateon

the front of the reel that made it suitable

for either automaticor free-spool casting.

Tension could also be adjusted by means

of a conspicuous winding key located in

the center of the front plate.

Regarding the proper use of theseearly

automatics, they were designed to be used

originally as either bait-casting or fly

reels (In 1897 Thomas Chubb [catalog]

recommended his reversible butt rod, i.e.

a rod that could be used for either fly- or

bait-casting, for use with the automatic

reels). Still, this was a sorlrce of some

confusion for many early anglers, and

sporting periodicals of the late nineteenth century contain many letters from

inquiring readers wanting to know if

they could use automatics for minnow

casting.

T h e Y & E automatic reels were made

for many years. In 1920 they were marketed by the Horrocks-Ibbotson Company, direct successors to Yawman &

Erbe. A Horrocks-Ibbotson catalog of

that year lists the smallest style A reel for

$10.00 and the large styleC for $14.00; the

no. 1 and no. 2 Old Reliables sold for

$7.50 and $9.00. Prices were about the

same some fourteen years later.

For the reel collector, the earlier Y & E

models are particularly desirable because

they were made for only a few years.

T h e s e were made of unplated brass,

bronze, nickeled brass, and hard rubber.

T h e aluminum reels were manufactured

for more than fifty years and arc by no

means rare items.

T H E FRANKLIN SMITH

AUTOMATIC

Between 1880 and 1890, there were

close to fifty patents issued relating to

fishing rrels, some of them bizarre and

unwieldy creations and doomed to fail-

become detached from their anchoring

posts; the Y & E is a prime example).

It is this second model of the Franklin

Smith automatic that is significant, for

regardless of its eventual fate, it was t h e

first automatic w i t h a truly modrrn form.

Still, like the first version, this model, for

some reason, is noticeably absent k o m

any angling literature of the day, and I

have found n o evidence that it was ever

manufactured for sale. Like many reels, it

may have had a small but fatal flaw.

Whatever the reason, the Franklin automatic's commercial failure is a n interesting mystery of the period.

T H R E E O F A KIND

A n enrly Ynrumnn and Erbe reel,

circa 1885, illu.~trati n g the linr-wrap

brakr pnd o n t h r linr-releare lever

ure, but others were quite efficient and

later became very successful (both baitcasting a n d fly reels, including those

designed by the Vom Hofe brothers, John

Kopf, and Thomas Chubb); yet only a

few automatic reels were patented during

this same period.

O n e of the more notable examples,

which evidently never got off theground,

was invented and patented by Franklin

R. Smith of Syracuse, New York, o n July

26, 1881 (one-half assigned to Willis S.

Barnum). Its appearance was similar to

the Y & E (see illustrations), but had a

lower profile and a spool covering the

gears (the spool of the Y & E is of a skeleton type, completely enclosing but leavi n g t h e gears of t h e reel exposed).

Although the patent drawings show the

usual features generally associated with

automatic reels, including a braking

lever and line guard, this model apparentlv suffered severe defects. for within a

year Franklin Smith was issued another

patent o n the same reel, but with several

modifications. According to the patent

claims, this new model (patented June

20, 1882, see illustration) featured five

major improvements: 1. the reel was

made to be used with interchangeable

spools (one of the few automatics ever

made claiming such a feature), 2. the line

guard was an integral part of the braking

lever (which may have been a serious

flaw), 3. the s h a p e of the line guard

(which was fitted with a "lateral inlet for

the introduction a n d removal of the

line"), 4. a spool that fitted over the tension spring and gears and thus protected

them from water and dust, and 5. a square

post within the spring housing designed

to allow easy attachment and removal of

the spring (one of the chief faults of automatic reels-including contemporary

models-are springs that either break o r

Shortly after 1900, the Kelso Automatic

made its appearance, a reel that subsequently gave rise to at least two other

automatics that were practically identical, the Rochester Automatic and then

common feature o n many later automatics.

T h e third reel to rvolve from the Kelso

was the famous Pflueger Superex, whit h

made its appear-ance sometime around

1920 (see illustration). Nearly identical in

form and size to both the Rochester and

Kelso, it became an enormously popular

automatic and was claimed by Pflueger

to be the best automaticof its day. LJnlike

the Kelso and Rochester, thesuperex was

fitted with a tension-relief device located

inside the reel, a longer braking lever, a

main-spring tension release, a n oiling

port o n the back plate, a n d a sliding plate

o n the lever arm that made it adjustable

for free-spool casting o r trolling. Later

models of the Superex (circa 1930) came

with a modified brake release consisting

of a curved arm fitted into the top of the

braking lever.

R e g a r d i n g sizes, l i t e r a t u r e of t h e

period indicates the Kelso and Rochester

were made i n a single size (3%-inchplate

diameter), while the Superex came in two

styles, both with the same diameter but

with different pillar widths (Y inch for the

no. 775, and 1%inches for the no. 778). All

of these reels bear the November 19, 1907,

patent date stamped o n the winding cap.

T H E C A R L T O N AUTOMATIC

r

l G - 4

-

rlG-5-

Patent drawings (1882) for Franklin

Smith's automatic fly reel. According

t o J o h n Orrelle, it is t h e first

automatic fly reel w i t h the "modern"

form.

the Pflueger Superex (see illustration).

This reel, patented November 19, 1907

(see illustration), was made from aluminum; its chief feature was the looped

braking lever similar to the one found o n

the Utica reel by Horrocks-Ibbotson.

Later models of the Kelso had levers of

solid construction such as those foundon

virtually a l l a u t o m a t i c s after 1925.

Around 1910 the Kelso was advertised

under the Diamond Brand and distributed by the Norvell-Shapleigh Company.

T h e Rochester Automatic was virtually identical to the Kelso, except for a

slightly different base-plate and a checkered design stamped o n the edge of the

winding cap. T h i s reel, along with the

later models of the Kelso, was a l s o

equipped with a rectangular line guard, a

A less familiar automatic reel dating

from the same period as the early Kelso

a n d Rochester reels w a s the C a r l t o n

Automatic, made and distributed by the

C a r l t o n M a n u f a c t u r i n g C o m p a n y of

Rochester, New York (see illustration).

Somewhat similar in appearance to the

older Y & E (an extremely wide reel with

the shape of a coffee mill), the Carlton

was made from a combination of alumin u m and German silver and came in one

size only. It was one of the few automatic

reels carried by William Mills & Son; it

sold for approximately $5 in 1910.

MEISSELBACH AND MARTIN

AUTOMATICS

August F. Meisselbach was one of the

most inventive and prolific reelmakers in

T h e Carlton automatic, o n e of the

few automatic reels sold by

W i l l i a m Mills and S o n

I T w o rrnrnplrr o j rrn,rniitonmt~c

fly rrrlr: P b K Rr-Trrtv-It ( l r j t ) and Fly Cl~nrnp(rlglrt). hotli irrrn 1940

America. His famous Exprrt ant1 Rainbow single-action reels werr the favorites

for tens of thousands of Arncrican anglers

for more than half a century. T h e first

Meisselbach automatic, howrvrr, ditl not

appear until 1914 (patenterl J u n e 30.

1914). T h i s reel, measuring 3'5 inc,hes in

diameter, was made of German silver and

suitable only for the heavicst rods; at well

over a pound in weight, this was one you

didn't want to drop o n your foot!

T w o later Meisselbac-h a u t o m a t i c s

were the 655 Automatic ant1 thr no. 660

Autofly Reel (circa 1920, see illustration).

Both of these reels were madc of aluminum and were considerably lighter than

the older 1914 model. Typical of thr Mt5isselbach genius for locking dcvic.es (such

as those found o n the famous Triparts,

Tak-a-Parts, a n d various occan reels),

both of these automatics featured ;I knob

o n the underside of the reel for rrlcasing

the bottom plate, as well as an adjustment for free-spool casting o r trolling.

T h e Martin Fishing Reel Company of

Ilion, New York (later of Mohawk), was

one of the first manufacturers of automatic reels in this country, and they produced what are possibly the most pol)ular

automatic reels ever made (scr illustration). First patented o n July 26, 1892,

with later patents issued in 1895, 1897,

and 1903 (others pending at the time), the

early Martin reels are significant brcause

they set the form for practically all later

automatics; indeed, because of their thoroughly modern appearance they are casily mistaken for more recent reels-so

much so that Martins in earlier catalogs

look incongruous and strangely out o f

place.

Identifiable by t h e flower p a t t e r n

stamped o n the edge of the winding tap,

earlier reels were made of German silver

and came to be known generally as thc

Martin standard reels. Later these were

made from a l u m i n u m with frames of

German silver, and by 1905, entirely of

a l u m i n u m . T h e s e early reels-those

made circa 1910 to 1915-were fitted with

a tension-release device (cylindrical in

shape and pulled out to release the tension of the mainspring), a brake-release

lever that could be adjusted by a fingerplate to put the reel into free-spool position (there were at least two variations of

this adjusting plate prior to 1920),a n d o n

later models a rectangular line guard.

Some of theearlier Martins (those bearing the Ilion patent) show oneof thegear

wheels partially exposed on the underside of the reel, had riveted frames, and

were stamped with the inscription Lint=

Out Herr o n the inner surface of the bott o m plate. L a t e r models h a d bottom

plates modified to enclose thegear wheel,

hut with a still-discernable bulge where

the wheel protruded beyoncl the normal

limits of the circular gear housing; these

same reels were assembled with screws

and did not have the stamped inscription.

For many years the Martin automatic

was available only in the standard model,

which came in four sizes: the no. 1, 2, 3,

and 4 reels-the latter a large-capacity

model advertised as the salmon reel. In

the 1920s, Martin introdtcccd the FlyWate reel (1924) and the large Trolling

Automatic, both of which hecame very

popular. Like many other rrels, prices for

the Martin were high when the reel was

first introduced, hut came down once a

market had been firmly est;cblished. In

1905 the salmon model sold for approximately $9, while in 1924 the price was

down to $5.

SEMIAUTOMATIC REELS

I n addition to the various automatic

reels appearing between 1880 and 1900, a

few others were patented that combined

I

both m ; ~ n u a l and automatic retrieve.

Most of these were imaginative contraptions, but impractical and short-lived. At

least two of them rmployed spiral-ratchct

gearing and a pull-string like that found

o n toy tops. O n e of these, invented by

Granville E. Metllcy of Hopkinsville,

Kentucky, appears to have been mainly

built from sewing-thread spools! Another

similar rr.t.1, patented I)y Charles F. Gillet

o f Springfielcl, Illinois (pat. no. 389,070,

Septem1)c.r 4, 1888), worked on the same

principle, a n d while more elaborately

constructed, seems equally improbable.

Both of these rigs wrare outrageous, and

only an extra arm or hand could have

madc them usable (in nrither case were

models submittrd). A third semiautomatic was invented 1)v Charles Bradford

(patented June 19. 1888). and although it

at least maintainctl the lines of moreconventional reels, it was, like the other two,

soon destined for oblivion.

T w o modern rrcls of the 1940s that

employed ratchrt grxring were the P & K

Re-Treev-It (Pachncbr & Koller, Inc.) and

t h e Fly C;hamp ( C h a m p i o n S p o r t s

Equipment Company, see illustration).

O n both these reels, line was retrieved o n

the upstroke of a n extension lever (on the

Fly C h a m p this It,ver co~cldbe folded

away for strictly manual retrieve), and

while both functiont,d basically as designed, there were several drawbacks to

each. For one thing, operating the lever

with the finger as intended involved an

awkward shifting aro~rntlof the grip o n

the rod, a fatiguing maneuver involving

an unnatural flrxing of the little finger.

Added to this was the irregular start-stop

motion of the spool, which retrieved line

with uneven tension and likely increased

problems of line tangle. Finally, neither

of these reels hati satisfactory clicks, a

point apparently neglrctrcl because of

concentration o n the novel retrieving

w"

*\w

[

/

L

-

e

b

.

c *3

@

m

e

<-.i

f'/

p2 k2\

*

b

I

q,

a

'9

b

6

R e p r e t m t a t z ~ ~automatzc

e

fly reels, czrca 1907 to 1920

Center: Kelto automatzc, czrca 1907-1910

Clockwztr from top: Early Martzn automatzc, czrca 1910-1920;

Mezttelbach Autofly, czrca 1920; Utzca, czrca 1915-1920; Early Martzn #3;

Pfleuqer Suprex, czrca 1920; and fzrst Mezstelbach automatzc, czrca 1914

mechanism. While the (.lick o n the Fly

C h a m p was satisfactory at bvst, the one

on tho Rr-'Ii-revc-It was made in such a

way as t o makr playing ;I fish directly

from the rrrl virtually im1,ossible because of I-ongh vibl-ations tlirratening to

shake thC rrcl apart when line was pulled

from it.

A morc rccent form of this typeof reel is

the DeWitt Re-Treeve-It, which appears

to be built on the same patcmt as theolder

P & K model. With a somrwhat more

strearnlinrrl shape, the I c v r ~of this reel

has been rxtrntieci considrra1)ly. T h i s

makes the opet-ation of the lever a less

tiring maneuver.

MODERN AUTOMATICS

T h e basic form and operation of the

automatic fly reel was well established

with the introduction of the Y & E, Martin, and Meisselbach reels. Between 1900

and 1940, a number of other firms produced them (Perrine, Shakespeare, Hedd o n , Horrock-Ibbotson, etc.), but the

overall a p p e a r a n c e of t h e a u t o m a t i c

remained the same. Ocean City made a n

automatic fitted with handles that could

be used either manually o r automatically

(the model go), Shakespeare advertised

o n e w i t h a level w i n d ( t h e n o . 1838

W o n d e r - F u l l ) ) , a n d m a n y new freestripping reels appeared. Most companies made both horizontal a n d vertical

models, and a very few offered reels with

interchangeable spools (in the 1970sGarcia made this a strong advertising point).

Aside from these minor innovations and

certain changes in construction materials, automatics have remained essentiallv the same.

Regarding the use of automatic fly

reels, opinion is generally divided into

two ,groups, with strong feelings evinced

by both; those w h o use and like automatics are wedded to them irrevocably, while

others find them better suited for doorstops. For a thirdgroup-mostly angling

editors w h o are hesitant to state explicit

opinion-they are a sometime thing.

Particularly in the early part of this century, automatic reels were held in high

esteem, a n d a great deal of space was

devoted to their praise. Among others,

0. W. Smith, angling editor for Outdoor

Life in the twenties, wrote a number of

articles o n automatics, including them in

a piece o n the "Dry Fly Reel." For many

anglers though, putting a n automatic o n

a fine fly rod was like tying a brick to it.

T h e horilontal reels werr especially disliked, since they were comparatively

heavy and often put a peculiar torquing

motion into a rod-destroying its feel

and balance.

AUTOMATIC FLY REELS:

P R O AND CON

T h e following two narratives, taken

from early sporting periodicals, describe

both the drawbacks and virtues of the

automatic fly reel.

T h e story told by "C.D.C." appeared in

a n 1887 issue of Forest cL Stream, and

while written before the automatic had

been fully developed, points out the troubleson~egremlins that somtimes hid in

the spring mechanisms of the automatic

-contemporary models included. It is

very likely that the author was describing

the old Y & E reel, a model known for a

spring that sometimes came "unhitched."

Writing for Outdoor Lifr in 1919, Jack

Maxwell relates a disastrous encounter

with a black bass, in which he becomesin

immediate and solid convert to the automatic. Done in by the limitations of the

single-action reel and demonic cockleburrs, he advises anglers to stay well clear

of both. T h e two accounts follow:

"EXPERIENCE W I T H TACKLE"

To the I.:ditor, Forr.tt cL Strcam:

Perhapsit would be in order just now

to say that the article which appearcad

over my signature in your issur of July 7

was written some four years ago and has

only now made its way into tlic printel-'s

hands.

Sincr writing it my opinion in regard

to reels has changed a n~rmht.rof times.

Since about the year 1865, at which

time my parents moved hcrc from Massachusetts, I have devotetl morr o r less of

my tinic to Fishing For trout. I early

learned the use of the fly-rod, and from

the time I first began to handle the reel

until the, prt.sent time1 havc. never found

a reel that was just as it ought to be. I have

bought a n u m b e r of rerls a n d used a

number of different kinds, and still have

never found one that was all right. Perhaps it is my fa~llt,but if t h t ~ c i anything

s

that will cause an angler trouble and expense it is a poor reel.

I thought when I wrote the article

referred to that I had found the thing I

h a d l o n g been looking for, a n d that

henceforth I should have n o trouble with

slack line, broken tips, and accidents of

that nature. When the next September

came, and I had made preparations for a

trip to the Connecticut Lakes, Parmachene Lake and the Rangeleys, I did not

think it necessary to provide myself with

another rrel, more esprcially as a good

part of my way was to be through the

woods, where all the luggage must ht

earl-ied o n my hack, and I well knew that

every pound would grow to he a hundred

before I had carried the pack ten miles.. . .

T h e morning after our arrival at J o h n

Danforth's I put my tackle together ant1

startetl out to try my luck at catching a

five-pounder, but just then five-pound

trout were a little scarce, so I had to content myself with some of about a pound

weight. T h e reel worked all right for a

time, but a b o u t n o o n I succeeded in

h o o k i n g a fish m u c h larger t h a n any

before, and then I noticed a little hitch in

thc internal arrangements of the mechanism. At first it would g o a l l right, then it

would seem inclined to dispute the rights

of t h e l i n e w i t h the fish, but it wouldsoon

r e p e n t of b e i n g s o h a s t y a n d m a k e

amends by giving h i m nearly all the line

it had. But evidently that was not just

right, for then it would sulk and refuse

most decidedly whether to take back the

portion of the line that the fish had got

through with or to g i v e u p any more. T h e

state of my mind at that time could be

easily imagined, hut would be hard to

describe. At last the reel got over itsobstinancy and went along as well as ever, and I

had begun to have hopes of being able to

secure the fish, when as i t made a desperate plunge a n d r u n for liberty, I felt something s n a p inside the reel, ancl then there

was such a whirring noise that o n e would

think a n old-fashioned clock was getting

ready to strike, and the reel was dead. T o

say that I was vexed would he to state it

very mildly indeed. T h e r c was 50 yards of

l i n r out and a good fish o n the end of it,

and n o prospects of being able to get it in

i n any k i n d of shape. My anxiety in

regard to the fish was soon released by his

g o i n g away somewhere ancl t a k i n g a

good leader and three flies with him. I

succeeded, after a time, in getting the line

o n the reel and started for camp, where I

immediately began to take the reel apart

and ascertain the extent of the damage. I

found that the spring had become unhitched at one end, and after working o n

it all the afternoon succerdecl in getting it

back together again.

After that it went along quite well for

two or three days, but I ciid not take any

comfort with it, for I did not know how

soon it would "baulk up" again. At last,

one afternoon as we were beginning to

fish, snap went the spring. It was broken

and as a reel was of n o use, but as a n

infernal invention for keeping a m a n

from enjoying himself it was a decided

success. I immediately returned to camp,

and was expressing my opinion of the

reel in quite decided terms, when an old

gentleman w h o was present i m l ~ l i e dhis

readiness to deprive himself of a nice reel

he had for a sufficicnt remuneration, a n

offer which I at once accepted.

T h e careful reader will perhaps surm i s e before t h i s t h a t my o p i n i o n i n

r e g a r d t o t h e " a u t o m a t i c reel" h a d

changed, but for the benefit of those who

have not already come to that conclusion,

I will now state that, while theautomatic

is a good reel as long as it works well, it is

so liahle to get out of order and is so

expensive to keep in repair ( a n d if broken

in the woods it cannot be mended), that I

think I am justified in saying that it is a

good reel not to have.

I have just got a new reel from another

well-known dealer, and expect soon to

find out what the timber is with that.

C.D.C., Northumberland, N.H.,

July 9, 1887

WHY I USE AN AUTOMATIC

(Outdoor Life, 1919)

S o far as I a m personally concerned, in

the angling game I much prefer theautomatir reel for fly fishing; let the other

fellow use anything he likes; m e for the

automatic, and as Mr. Post says, "there is

a reason", as the following brief experience will show:

Some years ago I was fishing one of my

favorite lakes for bass, using a flyrod and

a certain well-known single click fly reel.

My luck o n this particular day was not

phenomenal to say the most, however, I

was hanging a No. 4 fly in the face of a

bass now and then, and was, to all intent

and purpose, having a bully good time.

According to the custom I was carrying a

few feet of line looped gracefully in my

left hand as a sort of reserve fund and was

getting by very well in this manner, until

something happened that caused me to

sit u p and take notice of the extra line I

had in my left hand.

Extending o u t from the shore line o n

o n e side of the lake was a moss-bed reachi n g out possibly fifty feet and just at the

farthest edge of the moss a very athletic

bass was g o i n g t h r o u g h his m o r n i n g

calisthenics while rustling u p his breakfast. T h e idea occurred to me at once to

slip him something just as good, so I

proceeded to work out my line until I

could reach his city address and dropped

my Black G n a t right in his plate. N o

sooner had the fly landed than the bass

smacked his face together ancl by a s i m p l e

twist of the wrist and with a little assistance from the fish we had turned the trick

and Mr. Bass was o n the other end of the

string and it was u p to me to d o the rest.

Growing wild, without any help from

mankind in the way of cultivation, fertilization, "Burbanking" o r transplanting,

<growingabundantly and multiplying in

most any old kind of soil, is a weed, plant,

or something, in this precinct commonly

called by the inhabitants of the rural districts a "cockle-bur".

T h i s varmint of a weed is s o loving that

it will almost stick to thepolishedsurface

of a marble slab, and if a fisherman's line

becomes entangled in this aforesaid "Farmer's Curse", he had just as well stop and

unhitch right where he stancls. T h e fish

may spit the fly out of its face, but this

cussed i m i t a t i o n of a weed w i l l n o t

release a n anglcr's line.. . .

Soon as I hooked the fish I startccl to

work his noodle u p over the moss so I

could possibly land h i m at the shore

where I was standing. I succeeded in my

first performance very well and had him

c o m i n g toward the frying-pan, when

something seemed to go wrong in my

i m m e d i a t e vicinity; s t e p p i n g swiftly

backwards, I gave a t u g at the line I was

carrying i n my left hand, but there was

nothing doing; looking quickly around1

had lamped the cockle-bur. T o get my

line untangled instantly was impossiblc~

a n d I at once turned my attention to the

fish, but he had madr the most of the

opportunity and was under the moss.. . .

When I got loose my nice enameled line,

all I had to show for my vexation of spirit

was a little bunch of beautiful green lake

moss fastened to my hook.

After cooling down, or off, as the case

may have been, I figured in this manner:

I f I had been carrying my lineon a n automatic at this particular time, the aforem e n t i o n e d accident m i g h t not h a v e

occurred, as I would have had n o excess

baggage in the shape of a l i n r in my left

hand; therefore I beat it hack to town ant1

at once purchased an automatic reel. I

simply followed u p my hunch ancl have

lived happily ever since.

I prefer the automatic, because I can

handle my line with just a little bit less

exasperation at a critical moment, anrl

l i k e t w i n babies, these m o m e n t s d o

happen now and then.

But playing a fish with a single-action

reel, stripping in the line ancl letting it

fall at your feet is mighty finesport and i f

the other fellow prefers this method I say

let him "hop to it"; but if thercshould he

any cockle-burs along the shore line, he

had bettcr best shy of them while playing

his fish, as they arc liable to "gum t h r

game" at the critical moment just ;is they

did for me. Now just try torememher that

a difference in opinions is what makes

horseracing ancl fishing w o ~ t h w h i l r ~so,

always try to pick the winner, placc your

money o n your favorite, sit steady in the

boat and "may good luck follow you".

Jack Maxwcll, 1919

B

J o h n Orrrlle holds a n m t r r ' r dqqrre I T Z

p ~ y c h o l o g yand trachrs at Clackamas

C o m m u ~ z z t yCollrgr, nrar Portland,

Oregon. H e 2s an ai~zdtrout fzcherman

u ~ h oenjoys fzrhzng zrz nearby Azghaltztudr lakes. Hzs artzclrs h a w

appeared zn Fly F ~ s h e r Fly

,

Fl$he~man,

and Outdoor Llfe.

J o h n Harrzngton Kern?. A steel

engra~lzngfrom the October 1888 zssuc

of Wildwoods's Magazine ( ~ 0 11. , no. 6 ,

frontzrpzece)

Drv Flies on the Ondawa:

he Tragic Tale of

John ~ & i n g t o nKeene

It must be fifteen years since I

first read V i n c e n t M a r i n a r o ' s

Modern Dry Fly Code-not the

scarce first edition that P u t n a m

published i n 1950, but the more

affordable C r o w n reissue that

became available i n 1970.1 think

I read it i n one sitting, and I know I reread

it at least three times w i t h i n the next few

weeks. A true innovator of his time, Marinaro introduced m e , and a good many

American anglers, to the world of terrestrials and to a new approach to tying

dry-fly imitations of various mayflies.

H i s Jassids, Pontoon Hoppers, Thorax

Hackled Duns, and Quill-Bodied Spinners (all extremely effective patterns) are

n o w well k n o w n t o m o s t serious fly

fishermen of today. Marinaro's influence

o n fly-fishing wasprofound. H i s insightful book was a sharp contrast to and a

break from Ray Bergman's Trout ( a uery

popular book originally published i n

1939 and still considered a bibleon trout

fishing well into the sixties) that touted

Bivisibles, showy wet-fly patterns, and of

course the ultimate of nonimitation, the

Royal Coachman.

More important, however, and trans-

cending t h e particulars of Marinaro's

Code, its reissue marks the beginning of

an era, a renaissance i n American flyfishing i n w h i c h innovation, m o d e r n

science, and m o d e r n technology have

combined t o give u s h i g h l y efficient

tackle, highly effective imitations, and

remarkably successful techniques for the

capture of fish w i t h a fly, especially the

dry fly. Theserious fly fishermanof today

has by n o w read Swisher and Richards,

C a u c c i a n d Nastasi, W h i t l o c k , a n d

Schwiebert. to n a m e a few. H e isastudent

of the natural history of both aquatic

insects (entomology) and fish (ichthyology) and probably knows a little about

fish culture and the physics of rod tapers.

I n short. he is. more sobhisticated about

his sport ( i n an absolute sense) than at

a n y o t h e r t i m e i n t h e history of i t s

development.

But h o w does this relate t o J o h n Harrington KeeneKeene, at his worst, was as

innovative as Marinaro. H e practiced

dry-fly fishing o n the Battenkill as early

a.r 1886, the same year Halford published

i n England his Floating Flies a n d H o w to

Dress T h e m and well before Theodore

Gordon's experiments o n the Beaverkill.

Keene fished w i t h terrestrial imitations

that employed jungle cock nail feathers

( a la Marinaro's Jassid); he tied corkbodied dry flies; he introduced Americans

to extended-body dry flies;* he had a good

working knowledge of aquatic natural

history; he fished small midges; and he

wrote about all t h i s i n t h e American

Angler (1885), the American Field (1889),

and in seueral books o n fly-tying and flyfishing. I n other words, this m a n began

telling t h e American angler about entom o l o g y and innovative fly-tying and

fishing techniques often associated w i t h

the late 1960s and 1970s, and he did it a

century ago!

Keene's contributions t o American flyfishing have never been fully recognized

by angling historians, nor did these contributions have m u c h of a n influence o n

his contemporary American fly fishers.

W h i l e Marinaro's Code was uery influential and is today considered a benchmark

of the beginning of a modern renaissance

for the gentle art, Keene's proclamations

evidently fell o n deaf ears and failed to

induce any revolutions or evolutions in

American fly-fishing. It is the intent of

this essay t o present to the readers of the

Wildwood's Magazine, a rare, shortliued sporting periodical that was

published by Fred Pond (pseud.,

W i l l Wildwood). N o t e that i n addition

to Keene's "Memoir" by Pond, t h f

issue contained an article by Keene

( " T h e Salmon," p. 265).

P R I C E , 20 C E N T S .

S D W ~ ~ O D

i'

,

I

.

OCTOBER, 1888.

--..

,

.

omce

So.6.

rccolL.~-chrs

,..,I

i~niv

atrtllc

c .P,,SC

~

WILDW00D PUBhISHING COMPANY.

Cl4lCAGO: 166 L A S A b t l E S T R E E T .

: 251 BROADWAY.

NEW Y O R K~.

.

.-

-- - -

...-

.

..

CONTENTS:

rroo\i\piece- Pc~rrr.,it

of J o h n Harrington Keenc.

S c u l l ~ ~for

~ gMallards

l l l t ! ~ t r ; ~ l ~I<&,

~ ~ lIK

. 1:. ~.~:[/;t!,<~zvt//

.

..,lllllr ,,I

"

\l,lrl 4,,v1 51,11a,r,,g

A Mernuir of J. Harrington Keenr . . . . . . . . ,

Aulu!lm Sports

A Poem. /iy /soc,l' ,lfr/.r/ic,n

.

f'r.l;nc Chicken Shooting. lllu\tr.ttrrl.

/<v Ra,rh/cr

A Floriila Cvun l i u n t . /iy/. .lX,rlitrrr.r .fl,rr hy

A,.,!.

,

r

o u r ~ a l n cF l \ h and Fnhinl:

,

1 I.'

I

Nn V I

.. 1.1 ,,

'"I I

. .

,

American Fly Fisher a biography of J o h n

Harrington Keene and a n examination of

t h e w r i t i n g s of t h i s k n o w l e d g e a b l e ,

innovative fisherman.

.,

1)

T h e Salmon.

llllllllll.lll

. .

.

. .

1.t;

.

. .

"

"bl)

.

.

.

.

256

.

'Si

75,

\Vr.t"

. .

1111

c t ~

I:!, ,/ //lrrrinl./r,nA;z.rt,,.

I.#.iil:~illill I IV \I I L , , ~ ~

2h5

,

"

27s

. .

,

.

276

1lr/,k,,v8,/

27s

.

231

.

24;

22,

:11<

s ' :

:.#I

,. , .

:<.:.

..

.

,

,

8 ~ 8

,

F.>.tvr'. T . t l ~ : c

'T ,,,, ,:', 14,:

I . !.' ,: , I ' ,.t,y

v ,.,, ,,. 1:. . , , , I

it,,'

.. I , , ; ,a,$..

.

fkl qlt,L,tti8~: ".4sl~e>m<~>cc>

!tic

" of PI :O . . :,.!,. 1 I ' . , . ..r II ,.,,,II',.,c,,c,"

/ .

. .

T!>< (;,,,,!,,:, s.ttcr

b, If,,,,, .l/,,/<,~/,?,

.

1. rt d : : ~ !A,Ivcnt!irc> uf Ned 1iunlI:ne

I3.trtYl /<v I!;//

A I

I

t;famm,.

'' .*rm,.rt,=mv

,

.

-

I ,

IIll

I

..

.

8

..

. . ' , . : I

..

-

..' , .

I

I L . l 1

1 . " .

I

I

8 .

, . # ' . I .

1',*

I , . , ' .

,. 1 , . .,,

,,,,,.

\.11.11,,,. .,,,,II.

. " . . > , , % 1 , ) . Il , , l l I . . < i . , l

:Ill.llt..

I

, . , .,

..,.

I.,,,,,,

I,,.

' . ~ , ' ~ l . l ~ ~ .I '' ~

I J~I Il l~. Il~l ~~ I I I N C

GI I M I ' A N Y , 166 l.a Snllc St., Chaca~o,Ill,

Part I: The Biography

John Harrington Keene and his wife,

Anna, emigrated from England to the

United States in 1885. Within a year after

their arrival they settled in Manchester,

Vermont. An informative biographical

sketch o n Keene, written by Fred Pond

and published i n the October 1888 issue

of W i l d w o o d s Magazine,l gives many

details concerning Keene's life prior to

his coming to this country. Rather than

excerpt highlights from this memoir, I

have chosen to include it in its entirety,

with annotations. I caution readers that,

due to logistics, I have not been able to

check the reliability of all of the information contained in Pond's memoir. I note,

for example, that Keene was born o n

December 19, 1855 (to John and Rebecca

Sarah Keene), not in 1856 as stated by

Pond.2

J o h n H a r r i n g t o n Keene w a s

born at Weybridge, a pretty village

o n the Lower Thames, England, in

1856, and is consequently but 32

years of age, though the amount of

work a n d sport connected with

matters piscatorial he has accomplished, is out of all proportion to

his years. His fishing career may

almost be said to have been commenced in the cradle. H e was the

only son and close companion of

his father, a famous Thames professional fisherman, from his earliest years. Mr. Keene, Senior, who

q u i t e recently died at Windsor,

was, when the son was quite young,

chosen fisherman to Queen Victo-

ria, and presided over the magnificent preserves of Windsor Great

Park for fifteen years, where young

H a r r i n g t o n K e e n e b e c a m e acquainted with Buckland, Francis,

Manley, and a host of other patrician anglers, accompanying several of them to most of the best

fishing waters of Europe and the

British Isles, sometimes as a n

attendant, and at others as a personal friend.3

It is natural that a n ardent loveof

fishing and great natural powers of

observation should produce a writer o n fishing subjects. When but

sixteen, Mr. J. H. Keene began his

career with the pen, in the "Glob?

C h u r c h Strert, Weybrzdqe, Enqland

Kerne runs born zn Weybrzdqe zn 1855.

T h e p h o t o 1 7 from a poctcard ( c ~ r c a

and Traveler," a well known London evening paper, then edited by a

now famous physician, Dr. J. Martin Granville, and also contributed

sketches to "Once a Week," then

edited by G. Manville Fenn, the

well known novelist. Very soon followed copious contributions to

"Land and Water," " T h e Field,"

and the "Morning Advertiser," a

large daily sheet under the direct i o n of t h e a c c o m p l i s h e d C o l .

Alfred Bates Richards. About this

time also-though previously intended for commercial life-Mr.

Keene became assistant to his father and determinately pursued journalism and angling, natural history and authorship. By the time

Harrington Keene had reached the

mature age of twenty he had gathered material for his, as yet, magnum opus, "The Practical Fisherman." H e had fished for repeatedly

and caught every fish swimming in

British waters, and had compared

notes with the best fishermen of the

day. His chief angling friend at

that time was the late Rev. J. J.

Manley, an amiable and profoundly learned clergy man and author of

a charming work, "Notes o n Fish

a n d Fishing," which originally

appeared in the "Morning Advertiscr." alternatrlv with articles on

similar subjects from the pen of

Mr. Keene.

About this time Mr. Keene, pursuing his bent, left home a few

miles, and began business as a professional fisherman on theThames.

H e was successful beyond the average, as the son of such a "practical

fisherman" as his father, could

only be. About this time he had

contributed some especially inter-

esting notes o n the parasitic diseases of fish, (for Mr. Keene is a

microscopist, being then a member

of the chief microscopical societies)

to the now defunct English "Country," and became intimately known

to its manager, who also was part

owner and manager of the "Bazaar

Exchange and Mart." Recognizing

Mr. Keene's general journalistic

efficiency, h e was invited toedit the

"Country," and sub-edit the "Bazaar," on most liberal terms. T h i s

position he undertook and filled

satisfactorily for two years, after

which he retired in favor of more

original and congenial journalistic

work. During this term the "Practical Fisherman" was published in

the "Country," and subsequently

in volume form, receiving very cordial and distinct recognition from

the critics.5

Mr. Keene was at once thereafter

understood to be an authority on

fishing matters, and a real catalogue of his contributions to the

periodical press would fill more

spare than we can here afford. He,

with a printer namedoates, founded the present London "Fishing

Gazette."G H e compiled and edited

"Little's Angler's Annual," a n d

wrote multitudinously for all the

prominent papers and magazines.

Finally in 1884, for rest and genui n e recreation, h e accepted t h e

position of head fish-keeper o n

Lord Northbrook's portion of the

river Itchen -the premier British

trout stream. Whilst here he wrote

a long series of articles for boys in

the "Boys' O w n Paper," and his

recently published "Fishing Tackle; its Materials a n d M a n u f a c t ~ r e . "Finally

~

Mr. Keene decided

to visit this country, of which he

had formed enthusiastic visions,

( n o t yet broken, he tells us, by

unfulfilling reality), which he did

in 1885. Whilst here his father died

suddenly, and he not being available, the a p p o i n t m e n t passed to

other hands than his son's. T h e n

Harrington Keene decided to make

his home among us, and being an

expert in all kinds of tackle manufacture as well as a n expert with the

pen, he wrote "Fly Fishing and Fly

M a k i n g for Trout," (0.J u d d &

Co.,) a n d finally engaged i n fly

m a k i n g for t h e benefit of t h e

numerous admirers of his books

and talents.8 Until quite recently

he has been associated with C. F.

Orvis, but has now removed to the

banks of the lovely bass lakeCossayuna, Washington county,

N.Y., where h e proposes to cornplete many a chef d'ouvre of the

piscatorial writer's and fly maker's

art, amidst congenial surroundings.

Mr. Keene is president of the

flourishing Greenwich a n d Cossayuna Game and Fish Protection

Club, of Greenwich, N.Y., and is at

present deeply engaged on a new

work, especially designed to aid the

purely amateur angler, which will

be published early next spring by

the enterprising publishing firm,

Nims & Knight, of Troy, N.Y.9

Based o n Pond's remarks and the material subsequently published by Keene, I

think it is fair to say that he was well

schooled in all matters piscatorial and

was probably well acquainted not only

with Francis, Buckland, and Manley, but

also with Halford, Ogden, and others

intimately associated with the develop-

THE

AMERICAN ANGLER.

A WEEKLY JOUIINAL OF FISH AND FISHING.

-TEKREE DOLLARS A YEAR.

BINOLE COPIES. TEN CENTB.

-

NEW YORK, SATURDAY, JULY 18, 1886.

1

1-

VOLUME VIIL, NUMBER 3.

OFFICE, 1 5 1 BROADWAY.

-

Masthrad of J4'zllzam C Harrzs'r A m e r ~ c a nAngler Keene'sserzes, mtztled "Hour to Makr Trout Flzes,"

commenced zn theSaturday, July 18, 1885, 7ssue(7~01.8, no. 3). T o our knowledge, thzs rerzer constztut~d

thr firrt tzmr that znrtructzonr for tyznq dry flzrs wrre mer offerrd to the Amerzcan anglznqpublzr.

ment of dry-fly techniques o n British

trout waters. But marc about this later.

Pond states that Keene arrived i n this

country i n 1885 and shortly thereafter

associated himself with Charles F. Orvis

in Manchester, Vermont. I t h i n k this

information is probably correct. Keene

published twenty articles in William C.

H a r r i s ' s A m r r i c a ~ zAng1r.r i n 1885.1°

Although Keene could have sent these

articles to Harris from England, more

likely, he was in the LJnited States at the

time. Unfortunately, n o datelines were

printed with these articles that would

establish for u s Keene's place of residence. I n 1886 Keene published a series of

three articles o n English bait-casting in

the American Angler. l 1 Again, n o dateline is given, nor does the text indicate

Keene's whereabouts. But in the March

20, 1886, issue of the American Angler,

two short paragraphs appear (Notes &

Queries Section ) that relate to his casting

articles. Here, Keene mentions that he

has had a "Changeof residence ...." Keene

also says, in the J u n e 26 issue of the

American Angler, that he ate his lunch

"on the banks of the Ondawa which runs

through the vale of content in which I

live." T h e Ondawa is the Indian name

given t o t h e B a t t e n k i l l , w h i c h r u n s

through Manchester, Vermont. In 1887 at

least ten articles by Keene were published

in the American Firld, all with a dateline

giving Manchester, Vermont, as Keene's

place of residence.12 I would guess that

Keene and his wife lived in the environs

of New York City in 1885 where he probably first met Harris (theAmerican Angler

was published there), and that he moved

to Manchester i n January or February of

1886 (the change of residence referred to

earlier).I3

It is not hard to imagine why Keene

chose Manchester, Vermont, as his place

of residence. Manchester, i n 1885, was a

resort t o w n of s o m e n o t e . F r a n k l i n

Orvis's prosperous Equinox Hotel was

filled by well-to-do tourists from New

York and Boston w h o had come to revel

in the rural charm of this quaint New

E n g l a n d village. Also, by this time,

Charles F. Orvis's tackle business, established i n 1856, was flourishing. By 1885

he had acquired a national reputation as

a manufacturer of good quality rods,

reels, and flies. His tackle included the

now-famous narrow-spool fly-reel with

perforated side plates, and cane flyrods

equipped with Eggleston's patented,

spring-locking reel seat. I n 1876, C. F.

Orvis tackle received a gold medal a t the

Philadelphia International Exhibition.

Orvis's reputation as a n important tackle

manufacturer was further enhanced with

the publication of Fishing with the Fly

(1883), which heco-edited with A. Nelson

Cheney.14 What better spot could Keene

have chosen to reside in? Here, he could

hob-nob with the affluent tourist crowd;

as an associate of Orvis. he could continue his career as professional writer, fly

fisher, and fly tier; and hecould spend his

leisure hours pursuing the trout o n the

Battenkill.

Evidence of Keene's enchantment with

his new surroundings can be found in the

August 7, 1886, issue of the American

Angler15 i n a letter (reprinted by Harris)

that he had sent to the British publication, Land and Water.

As I said above, I a m w r i t i n g

from the old Yankee State of Vermont, a n d i n a village which reminds m e of n o t h i n g so much as

t h e b e a u t i f u l t o w n of M a l v e r n

(Worcestershire), except that Malvern h a s n o s t r e a m r u n n i n g

through it, a n d this has. Here is a

genuine mountain stream, born of

the mighty Equinox, and the trout

are i n thousands, w i t h n o n e to

catch them, save villagers a n d a few

summer visitors. And these same

trout are of very respectable size,

unlike the generality of mountain

fish-that is, going u p to one and

one-half pounds, pretty frequently.

T h e r e is n o need to conceal its

name, it is the 'lovely' Ondawa in

the language of the Indians, a n d

Battenkill in the uncouth vernacular of the settlers. Ondawa let it be.

It is rapid and clear, shallow and

deep, i n alternation; n o w garrulous with mimic fury, now making

'sweet m u s i c w i t h the' enameled

stones.' B u t stay; S h a k e s p e a r e ' s

words remind m e that a poeticallyinclined friend has already apostrophised 'Ondawa' in strains

which all will agree rival anything

'1e immortel Williams' could have

writ. Pardon me, all-patient Editor, if I reproduce them as a valedictory tailpiece to this, my very

discursive letter.

ONDAWA

T h e high and massy mountains

roll along,

Wave-like, beside thee, dressed

in living green,

Whilst giant Equinox-a parent

strong

Of myriad rivulets, with royal

mien,

Head-gray is cloud-o'er

shades the daedal scene.

T h r o u g h dells and grots, through

festooned dreaming woods.

T h o u boundest, glad of heart,

in child-like glee

Mid plains of emerald, or

solitudes,

rI.l H E

>

Q

=

+- -

Dark with crag, or from the

canopy

Of leafy mysteryr thou hastest,

wild and free.

THIRTY-TWO PAGES.

\

@- O-.

curl,

Leaps the bejeweled trout. Then

richer far

T h a n Ophir's mine of gold art

thou, oh Ondawa!

And from thy limpid deeps, or

riffles whirl,

O r the translucent eddy's oily

not feeding on the natural insect. If

there are not some flies to be seen

about, depend upon it the fish are

after some kind of food they do see,

something in the water. Then try

'wums.'

There is no use whipping the

water with flies when the fish are

YO

TROUT-FLIES MADE WITH am BODIES AND SCALE WINGS.

prarar. ~$2.00

pra DOZENWe make these flies zs a novelty, but doubt if they will ever lake the place of the feathered flies, the use of~vhich

for s e v c d hundred years har proved their thorough efficiency.

They are dose imitations of natural insects, and are extremely durable; although delicate in appearance they are

to

practnelly indestructible. The wings are too tough to be torn, yet when in the water become pliable and

the tish no reststance, as do the quill w n g and other wings of a sim~larcharacter heretofore offered as a substitute

for feathen.

We print an extract from a letter published, not long ago, in

THEFISHING

GAZETTE,headed.-

"b4,lTbRIAL FOR W I N ( ; S OF ARTIFICIAL FLIES."

Wkot ir rrolly ~ t ~ r r r r c dsi rst,brfancr which ronrbincr fhc fiyYntss and brroya.ry of fhr ftafhrr in

tdc a b or wclf arrn f k wofrr,

~

with the fou,hntss m d p m r to rrtain if5 d u p e of fht qurlf. fqqtfhn w ~ f rke

k $1;~brlrfy.Ir*nrfiarmcy and trtfurr of tkr yofd brofrr'r ~ k z n and

.

the prnpnfy of briny rasrly staznrd or dyed, and t k : ~

*mafntol,nrfar as Iknmu, horyrf lo bc dtsrmrcrcd."-HIITERN.

..

\Ve afier the scale wing (not api.6t.scale ring) as the discovery which meets all the requirements mentioned in

the abobr letter.

. ----- .-.- Wc suggest the following as the most desirable to be made with Gut Bodies and Scale Wings :Hrown CoHin.

Deer Fly.

Gauze Wing.

Red Fox.

lllatk Ant.

Emenld Gnat.

Hoskins.

Red Spinner.

l;!a:k bnat.

Emerald 1)un.

Haa thorn.

Stone Fly.

lcluc Dun.

Fiery Ilrown.

Morrison.

Scarlet I his.

Cl.lrct.

Green 1)rake.

Orangc I3lack.

Solrlier.

CI,~

Uunc.

(;try 1)rakc.

I'alc Eveninx Dun.

Yellow hlay.

.

~

11.11:S \V1'l'11 CORK I1OL)II:S, FI.OATIS(; hli\Y-FI.IES, CADDIS.FI,II.S .\sL)

I'I,IES. M A ~ ETO O n n ~ n ass

.

S I Z E D E S I I ~ E D$2.50

,

PER I)()zI<s.

c]~c'(I.

17

A d i ~ c t ~ u of

n l Tru lrrr rcnt. lrnm list prices of FLIESwill be made on orders of SIX dolrl, ,,r ,,rr.r, .,,,,I

I i v ~\ I Y IIC'T t.e"t. on oxlrr. vf 1wnl.ve dozen or over.

-1

Copy from page twrnty-six of C. F. 0 n l i . s ' ~sixteenth catalog (circa 1889).

Thrsr .so-callrd "~7or~rlty"

f1ie.v are unqur.stionably the crealion.~of

J o h n Harrirzglon Keene.

I

T h e nature of Keene's association with

Charles F. Orvis is not completely clear.

O n page twenty-six of Orvis's sixteenth

catalog (circa 1889) trout flies made with

gut bodies and scale wings, as well as flies

with cork bodies, floating mayflies, caddis flies and cisco flies are offered for sale

(see i l l ~ s t r a t i o n )These

. ~ ~ are the flies of

John Harrington Keene, the same flies

that were described in .great detail in the

series of articles he published in the

American Anglrr in 1885 and in the

American Field in 1887 (vide ante). O n

page thirty-one of the samr catalog, fifty

patterns of salmon flies were advertised,

all of them English patterns. Evidently,

Keene supported himself during his stay

in Manchester by supplying Orvis with

his highly innovative trout-fly imitations, probably with the salmon flies too.

Keene also obtained additional funds by

functioning as a correspondent to the

more popular American sporting periodicals and to some British publications.17

Pond, in his memoir of October 1888,

states that Keene had recently relocated

his residence to the shore of Cossayuna

Lake in southern Washington County,

New York.lR My supposition is that he

moved because he had a falling-out with

Orvis. A l t h o u g h Orvis was a strong

believer in the imitation theory,lgI don't

think h e had m u c h faith in Keene's

"Exact-imitation flies" or the dry-fly

methods that Keene espoused. For example, see the accompanying illustration

JOHN HARRlNGTON KEENE,

Author of Fly Fishing and Fly Making, Etc., Etc., Etc.,

Artist in All Kinds of t h e

pinext m ~ t i f i e i aP

l lies

anb p l y - @ s h i n g

pu~es.

S I ~ E ~ : I A I . T I EStandard

R - - I ~ ~ Patter~ls.

~

Exact I~nitrrtionsof American insect^. in Feather,

Fur, Silk. ( J r i i l l , 1Ior.c II:tir, Itubber, Scale, Etc.. Etc. Thc New 1nterchange~I)le Raee,

Sal~llolland Tro~ltI.'ly. The Water I'roof-Winged Fly. Salmon Flies Made to Order. Every

llook nr~dSi~ellTcnted slid (;urrruntc:cd.

GREENWICH, N.Y

-

KrrnrS.saCI~~rrli.srni~~i1

lhal appmrrd in tlrr 1894 rdition of thr Directory of Grcrnwich.

Notr that Irr toitt.~"Esacl In7itation.s of Amrrican In.tcc~.s...."

from t h e Orvis catalog (circa 1889) i n

which the following statement is made:

We make these flies as a novclty,

but doubt if they will ever take the

place of feathered flies, the use of

which for several hundred years

has proved their thorough efficiency.

I s u r m i s e t h a t Keene n o t o n l y took

umbrage at this statement but also at not

being given any credit whatsoever for his

innovative flies, either in this catalog o r

in other Orvis advertisements.

I would also surmise that Keene's flies

didn't sell very well. T h e unsophisticated, native brook trout would take just

about any fly, and the gaudy, tinseled

attractor flies not only were less expensive t h a n Keene's creations, b u t very

likely were more attractive to and more

p o p u l a r with the Victorian angler.

Indeed, Keene as much as admits this in

the previously mentioned copy that he

sent to Land and Watrr reprinted in the

American Anglrr in 1886.

What chiefly impressed m e regarding trout fishing [in the I J n i ted States] were the two facts that

large flies u p to No. 9 Sproat, and

fishing down stream, were de rigeur. T h e floating fly is practically

unknown, and u p stream fishing

therefore an occult art, the mcre

mention of which is sufficient to

bring forth a smile of kindly contempt. Yet the brook trout here are

easily taken by the means employed. Here it is a charr [sic]-as

the latest dictum of the ichthyologists sets forth-and not a trout at

all, being but S a l m o fontinalis,

and its voracity is great. Probably

w h e n i t h a s been fished over

through hundreds of years by a

crowded population the necessity

for very light tackle will arise. At

present the generality of tackle here

is light only as regards the rod.

If, as I suspect, Keene badgered Orvis to

tout his flies more effectively and to give

him credit for his innovative contributions, O r v i s w o u l d have most likely

refused, a n d a parting of ways would

have followed. Speculative, obviouslybut I n o t e i n Mary O r v i s Marbury's

Fauoritr Flies (1892) the following passages o n page 382. These remarks accompany a plate of F. M. Halford's dry flies.

Some time ago, in the English

"Fishing Gazette," a correspond e n t s i g n i n g himself "Bittern"

wrote as follows:

What is really requirrd for the

w i n g s of artificial flirs is a substancr which combinr.~the lightness and buoyancy of thr feather in

t h air

~ a~wrll as i n the water zuith

thr toughness and powrr to rrtain

the shapr of the q u i l l , togrthrr

with the pliability, transpar~ncy,

and trxturr of the gold-beater's

skin, and thc proprrty of bring pasily stainrd or dyrd, and this material, .so far as I know, has yet to be

discoztrrrd.

Later, it was found that theinner

membrane of the scales of theshad,

red-snapper, and other fish was a

beautiful substance nearly answeri n g this description. Flies made

with wings of this membrane are

extremely durable and lifelike in

appearance; the wings are too

tough to be torn, but in the water

become pliable and offer to the fish

n o resistance; yet, attractive as they

appear, they have not proved very

p o p u l a r with fishermen, o w i n g

chiefly, we think, to a slight rustling noise they make when cast

through the air. It is doubtful if

this s o u n d is really any serious

objection to these flies, but it seems

to have been a fault that has prevented their extended use.

Keene himself had discovered the inner

membrane of the scales of fish could be

used as wings for dry flies, yet Marbury

(Charles F. Orvis's daughter) failed to

give him due credit. Further, mention of

Keene's n a m e is conspicuously absent

from her book. She must have known

about Keene's articles in the American

Anglrr and theAmrrican Field and about

his book, Fly Fishing and Fly Making-20

T o p : Frontispiece from American Game Fishes (1892) edited

by G. 0. Shields. T h e dressings for the flies aregiuen in a

chapter of the book titled "Fishing Tackle and How to Make

It" by J o h n Harrington Keene.

Above right: More of Keene's flies from the same work

I

Left: Couer of the third edition of Keene's Fly-Fishing and

Fly-Making (1898). T h e book contains two pages of

tipped-in fly-ty ing materials-hackles, wing materials,

floss, etc.

A contemporary photopraph of J o h n Harrzngton Keene's rerzdence at

9 J o h n Street, Greenwzch, New York. Keene re~zdedthere for at least

two yearr (1892 to 1894).

all of which exhaustively discuss his

innovative fly-tying techniques, his dry

flies, and his exact-imitation theory. Yet,

in all of her discussions of the floating fly

(albeit brief), only the names of Pritt and

Halford appear. Surely Orvis and Keene

must have had a bitter di~a,greement.~'

22

H o w long Keene lived o n the shore of

Cossayuna Lake, I'm not sure; by 1892 he

was listed in the Directory of Greenwich

as a fishing-tackle maker living at 9 John

Street in Greenwich, New York.Z3 Elsewhere in the same directory, it is noted

that Keene published a newspaper called

the Graphologist o n the fifteenth of every

month (graphology is the study of handwriting). I n the 1894 directory the same

address is given, and he has a n advertisement for his flies a n d lures (see illustration). Additional information o n Keene

during this period can be found o n page

fourteen of Islay V. H . Gill's History and

Directory of Cossayuna and V i c i n i t y

(1957).

...J. Harrington Keene, an English

man, graphologist and expert tyer

[sic] of artificial flies. H e lived in