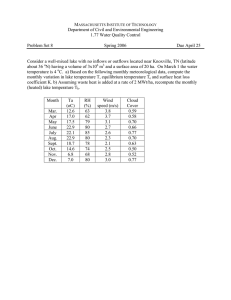

The Complete Trip Report for the Notakwanon, Labrador, 1998 2

advertisement