ProRege.March 2013.inside.indd

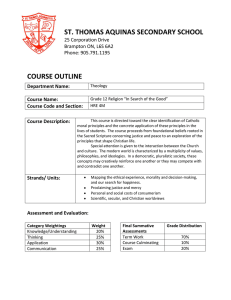

advertisement