article in press - American Heart Association

advertisement

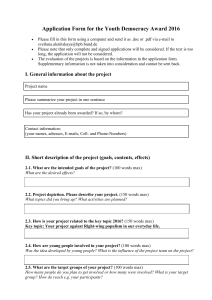

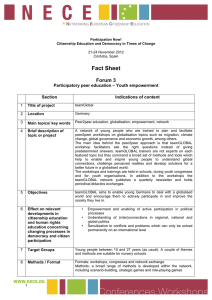

ARTICLE IN PRESS Achieving rapid reperfusion with primary percutaneous coronary intervention remains a challenge: Insights from American Heart Association's Get With the Guidelines program Rajendra H. Mehta, MD, MS,a Vincent J. Bufalino, MD,b Wenqin Pan, PhD,a Adrian F. Hernandez, MD,a Christopher P. Cannon, MD,c Gregg C. Fonarow, MD,d and Eric D. Peterson, MD, MPHa on behalf of the American Heart Association Get With the Guidelines Investigators Durham, NC; Lombard, IL; Boston, MA; and Los Angeles, CA Background The speed of reperfusion (door-to-balloon [D2B] time) is a well established performance metric for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Although preferably D2B times should be ≤90 minutes, it is unclear how consistently this is achieved in community practice, particularly in women, elderly people, and minorities. Methods We used the American Heart Association Get With the Guidelines database to study D2B times at 254 participating United States sites (2002-2006). Median D2B time and percentage of compliance with goal (percutaneous coronary interventions [PCI] ≤90 minutes) were assessed overall, over time, and among patient subgroups associated with the greatest delay in this time (older patients, women, and minorities). Standard generalized estimating equation was used to assess continuous trend, percentage of compliance (PCI ≤90 minutes) over time, and disparities in care based on race, sex, and age. Results Over the study period, 10 965 patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction who met eligibility criteria received primary PCI (36% aged ≥65 years, 27% female, and 17% nonwhite). The overall median D2B time was 96 minutes (interquartile range [IQR] 69-140 minutes). Only 44.8% of cases had D2B ≤90 minutes. Median D2B time improved over the study period (108 minutes at baseline [fourth quarter of 2002] to 82 minutes by the last study quarter [third quarter of 2006], adjusted P = .001). The percentage achieving D2B ≤90 minutes also improved (36.2%-58.8%, adjusted P = .003). Relative to their peers, patients aged ≥65 years (103 [IQR 74-153] vs 93 [IQR 67-133] minutes), women (103 [IQR 73-154] vs 94 [IQR 68-135] minutes), and minorities (108 [IQR 77-162] vs 95 [IQR 68-136] minutes) had significantly longer median D2B times. These subgroup disparities in the D2B persisted over the study period as compared with their peers. Conclusion The median D2B times with primary PCI have improved modestly in hospitals participating in the American Heart Association Get With the Guidelines program over the last few years but remain below ideal levels. The D2B times are particularly delayed in the elderly people, women, and minority populations; an issue that has persisted over time. These results highlight the ongoing need for national myocardial infarction quality improvement initiatives. (Am Heart J 2008;0:1-9.) Primary percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) has been shown to be the more effective reperfusion strategy than fibrinolytic therapy for patients with ST-elevation From the aDuke Clinical Research Institute and Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, bMidwest Heart Specialists, Lombard, IL, cBrigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, and dUCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA. Funding source: Get With the Guidelines-CAD is sponsored by the American Heart Association with funding in part from an unrestricted education grant from the MerckSchering Plough Partnership. Submitted November 12, 2007; accepted January 17, 2008. Reprint requests: Vincent Bufalino, MD, 801 S Washington 4th Floor, Edward Heart Hospital, Naperville, IL 60540. E-mail: vbufalino@midwestheart.com 0002-8703/$ - see front matter © 2008, Published by Mosby, Inc. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2008.01.010 myocardial infarction (STEMI), when performed rapidly by experienced operators and in a timely fashion.1 Shorter door-to-balloon (D2B) times have been associated with significantly lower mortality among patients undergoing primary PCI,2,3 leading the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines to designate the rapid performance of primary PCI, preferably with D2B ≤90 minutes, as a class IA recommendation.4 In addition, D2B time has been incorporated as one of the core quality metric collected and reported publicly by the Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services and the Joint Commission highlighting its significance. However, multiple logistic challenges often prevent timely reperfusion in routine clinical practice as compared with that seen in randomized clinical ARTICLE IN PRESS American Heart Journal Month Year 2 Mehta et al Figure 1 Study population flow chart. trials. 1,2,5-8 As a result, many institutions and professional societies have focused their attention on improving this established performance metric for patients undergoing primary PCI. 9-14 The Get With the Guidelines (GWTG) program of the AHA is a national quality improvement initiative that focuses on improving compliance with a number of evidenced-based therapies. 10-12 There was no specific focus in GWTG program on improving D2B times. Data from GWTG provide a unique opportunity to examine national trends in D2B times supplementing other national registries such as National Registry on Myocardial Infarction (NRMI) 2,5-8 and the ACC–National Cardiovascular Database Registry. 15 The main objectives of this study were to evaluate temporal changes in overall D2B times among patients undergoing primary PCI at GWTG between 2001 and 2006. We also sought to determine whether D2B performance metrics varied among elderly, women, and minority populations and whether any identified gaps in care had narrowed over time in these at risk populations. ment Tool (PMT) (Outcome, Cambridge, MA), which were pilot-tested in 24 Massachusetts hospitals by the AHA and the Massachusetts Quality Improvement Organization with the support of multiple organizations in Massachusetts. The collaborative learning model includes interactive learning sessions, teleconference, and electronic communication between multidisciplinary teams from hospitals in a variety of settings to facilitate the transfer of the “how-to” necessary to produce system-wide change. The PMT aids in concurrent data collection and decision support and also provides realtime online reporting features. After the success of the initial pilot phase in a diverse group of Massachusetts hospitals, the AHA adopted GWTG as a national program with introduction in Southern California followed by a phased introduction across the United States. The GWTG is similar but more contemporary as compared with NRMI. 2,5-8 Furthermore, unlike in NRMI, which focused on patients with acute myocardial infarction, the GWTG program focuses on improving the quality of care of all patients with coronary artery disease. In contrast to these 2 registries, the ACC–National Cardiovascular Database Registry 15 includes only those patients that underwent a cardiac catheterization and/or PCI. Clearly, hospitals participating in these 3 registries differ with some overlap. Methods Patient population The GWTG program Details of GWTG have been previously published. 10-12 In brief, the AHA launched the GWTG initiative focused on the redesign of hospital systems of care to improve the quality of care of patients with coronary artery disease. The GWTG is based on a collaborative model and the Internet-based Patient Manage- The GWTG-coronary artery disease database includes 248 915 patients enrolled between January 2, 2000, and September 20, 2006, from the 492 hospitals participating in GWTG–coronary artery disease initiative that had the capability of performing primary PCI and includes teaching and nonteaching, rural and urban, large and small hospitals from all ARTICLE IN PRESS American Heart Journal Volume 0, Number 0 Mehta et al 3 Table I. Baseline characteristics Characteristics N Demographics Age, median (IQR), y Table II. Performance measures Overall D2B time ≤90 min D2B time >90 min 10 965 4912 6053 59 (51-70) 36.1 27.4 16.9 27.9 (25-32) 58 (50-68) 31.9 24.5 13.8 28.0 (25-31) 60 (52-72) 39.4 29.8 19.4 28.0 (25-32) b.0001 3.5 8.2 .2281 .2650 Age ≥65 years (%) Female sex (%) Nonwhite (%) Body mass index, median (IQR), kg/m2 Medical history Atrial fibrillation (%) 3.3 3.0 Chronic obstructive 7.9 7.6 pulmonary disease (%) Diabetes (%) 23.1 20.0 Congestive heart 4.2 3.1 failure (%) Hypertension (%) 56.8 53.0 Hyperlipidemia (%) 45.7 45.1 Prior myocardial 14.3 13.5 infarction (%) Peripheral vascular 3.6 3.0 disease (%) Stroke (%) 3.8 3.2 Renal 3.0 2.2 insufficiency (%) Renal dialysis (%) 0.7 0.5 Smoking (%) 43.7 46.8 Anemia (%) 0.1 0.1 Alcohol (%) 4.5 4.4 LV ejection fraction 22.2 19.9 b40% (%) 133 131 Systolic blood (113, 153) (113, 150) pressure at admission, median (IQR), mm Hg 79 80 Diastolic blood (66, 91) (67, 92) pressure at admission, median (IQR), mm Hg P b.0001 b.0001 b.0001 .9349 Performance measures ⁎ Aspirin within 24 h (%) Discharge aspirin (%) Discharge β-blockers (%) Discharge ACE inhibitors or ARB in patients with documented LV systolic dysfunction (%) Lipid-lowering agent in patients with LDL >100 mg/dL (%) Smoking cessation counseling (%) 100% compliance with composite measures (%) D2B D2B time ≤90 time >90 Overall min min P 96.9 98.5 97.7 87.8 97.2 98.9 98.1 91.1 96.6 98.2 97.3 85.4 .0876 .0053 .0062 .0002 94.9 95.5 94.4 .1072 93.2 94.2 92.3 .0125 71.5 73.2 70.2 .0005 25.6 5.1 b.0001 b.0001 59.8 46.2 14.9 b.0001 .2520 .0371 4.1 .0028 4.3 3.7 .0030 b.0001 Data collection 0.8 41.2 0.1 4.7 24.0 .0688 b.0001 .5001 .5283 b.0001 Data were systematically collected for each hospitalization, including patient demographics, medical history, symptoms on arrival, electrocardiographic examination, inhospital treatment and events, discharge treatment and counseling, and patient disposition. 136 (114, 155) .1514 77 (66, 90) .2390 LV, Left ventrical. census regions of the United States. All patients presenting with chest pain or ischemic symptoms and ST elevation in 2 contiguous leads or new or presumed new left bundle branch block who had a PCI within 24 hours were eligible (n = 15 536). Patients were excluded if they were transferred from other hospitals or emergency departments or received fibrinolysis (n = 4394). The remaining patients constituted the analysis sample (n = 11142, hospitals = 254). Furthermore, for the evaluation of D2B trend over time, because very few patients were enrolled in the last 2 quarters of 2001 and in the first 3 quarters of 2002 (n = 177), these patients were also excluded for this analysis. Thus, the final study sample was composed of 10 965 patients enrolled between October 1, 2002, and September 18, 2006, at 254 sites (Figure 1). Data on patients were collected by participating hospitals without financial compensation. Case finding was based on clinical ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; LDL, lowdensity lipoprotein; LV, left ventrical. ⁎ In patients with appropriate indication and without any contraindications. identification of patients with these diagnoses as well as by retrospective International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, coding to permit the use of the PMT and other decision support tools adapted by hospitals in the program. Outcomes of interests The 2 main outcomes of interest included median D2B time and proportion of patients with D2B time ≤90 minutes. These end points were examined in overall population as well as in subgroups of interests that had the longest D2B times, that is, patients aged ≥65 years versus b65 years, women versus men, and minorities (nonwhite) versus whites. Statistical analysis All analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Research Triangle, NC). Data are presented as proportions for categorical variables and as median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. For univariate comparisons, we used χ2 tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon 2-sample test for continuous variables. The overall linear time effect on percentage of compliance was tested using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel method. The adjusted linear time (quarter) effect was tested by fitting multivariate logistic regression model to account for confounders and also standard generalized estimating equation approach to account for with inhospital clustering. Baseline patient characteristics in the model included age, race, sex, body mass index, insurance, past medical history (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, smoking status, dyslipidemia, prior myocardial infarction, prior stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and renal ARTICLE IN PRESS American Heart Journal Month Year 4 Mehta et al Figure 2 Trends in median D2B times (IQR, minutes) over consecutive calendar quarters. Figure 3 Proportion of patients with D2B ≤90 minutes over consecutive calendar quarters. insufficiency), and systolic blood pressure at admission. Finally, to examine if participation in the GWTG program had any influence on the trend in D2B over consecutive calendar quarters, we adjusted for quarter of enrollment of the sites in GWTG. We also evaluated interactions between D2B time over consecutive quarters with age or sex or race. An interaction term was considered to be insignificant if its P value was >.10. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the likelihood posed by subgroups of interest on compliance with D2B time ≤90 minutes. All P values are 2-sided, with P b .05 considered statistically significant. Results Patient characteristics and performance measures The baseline demographics of the overall study population (N = 10 965) as well as that stratified according to D2B time ≤90 minutes are shown in Table I. Approximately, 36% of patients were aged ≥65 years, 27% were women, and 17% were nonwhite. Patients with longer D2B time were more likely to be older, female, and nonwhite. Most comorbid conditions were also significantly higher in this cohort and included ARTICLE IN PRESS American Heart Journal Volume 0, Number 0 Mehta et al 5 Table III. Independent correlate of longer D2B times in patients undergoing primary PCI Variable Age ≥65 y Female sex Minority Calendar quarter of enrollment Body mass index Chronic lung disease Diabetes mellitus Congestive heart failure Hypertension Hyperlipidemia Prior myocardial infarction Peripheral vascular disease Renal insufficiency Prior stroke Smoker Systolic blood pressure OR 95% CI, lower limit 95% CI, upper limit P 0.815 0.836 0.760 1.044 0.735 0.763 0.686 1.025 0.903 0.916 0.842 1.063 b.0001 .0001 b.0001 b.0001 0.998 0.999 0.990 0.854 1.005 1.170 .5560 .9922 0.886 0.763 0.840 0.619 0.993 0.942 .0060 .0116 0.892 0.972 0.915 0.812 0.893 0.806 0.979 1.057 1.038 .0159 .5028 .1677 0.710 0.546 0.924 .0109 0.810 0.905 1.145 0.998 0.651 0.731 1.042 0.993 1.009 1.121 1.258 1.002 .0597 .3627 .0047 .3507 diabetes, hypertension, prior myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, and renal insufficiency. Only history of smoking was less common in patients with longer D2B. Left ventricular ejection fraction b40% was also more prevalent among patients with longer D2B. Compliance with most performance measures was lower for patients with longer D2B (Table II). Door-to-balloon time Overall, the median D2B was 96 minutes (IQR 69-140 minutes). Only 44.8% of patients had D2B ≤90 minutes. Median D2B time improved significantly between the fourth quarter of year 2002 and the third quarter of year 2006 (Figure 2) from 108 to 82 minutes (P b .0001). The most impressive improvement in this measure occurred in the final 4 quarters as compared with the first 4 quarters (median time 100 minutes [IQR 71-145 minutes] vs 90 minutes [IQR 66-127] for last 4 quarters vs first 4 quarters, P = .0056). In addition, the variability in this measure across sites also decreased over time (P value using F test b.0001; Figure 2). As a result, the proportion of patients with D2B time ≤90 minutes increased over time (from 101 [36.2%] of 279 to 146 [58.2%] of 251, P for trend b.0001; Figure 3). Thus, relatively 62.4% more patients were treated with D2B times ≤90 minutes in the last quarter as compared with the first quarter (absolute increase 22.6%). Again, the proportion of patients treated ≤90 minutes of arrival to the hospital was higher in the last 4 quarters (50.0%) as compared with the first 4 quarters (42.7%) (P b .0001). Even after accounting for differences in case mix as well as for within-site correlation, the overall linear trend over time for improvement remained significant (P b .0001 for improvement in median D2B time and P b .0001 for increase in proportion of patients with this time ≤90 minutes). Finally, linear trend for improvement in D2B persisted even after adjustment for the enrollment specific quarter of the sites in the GWTG program (P = .0011 for improvement in median D2B time and P = .0028 for increase in proportion of patients with D2B ≤90 minutes). Disparity among subgroups Results of subgroup analysis by age, sex, and race suggested important differences even after adjusting for patient medical history, body mass index, and blood pressure. Being old (≥65 years), being female, and being minority were the most significant predictors of the likelihood of receiving delayed primary PCI in the multivariate analysis (Table III). Median D2B times were 10, 9, and 13 minutes longer for elderly people, women, and nonwhites (P b .0001 for all comparisons; Figure 4). As a result, 8.0% fewer elderly people, 6.6% fewer women, and 9.9% fewer minorities were treated with D2B times ≤90 minutes as compared with younger patients, men, and whites, respectively (P b .0001 for all comparisons; Figure 5). This disparity in the D2B time persisted over time among various subgroups with the elderly people, women, and minorities continuing to have longer delay in D2B time and significantly lower proportion of patients in these subgroups having D2B time ≤90 minutes as compared with younger patients, men, and whites over time (Tables IV and V). Discussion Our investigation suggests that D2B times in recent years have improved significantly among communitybased hospitals participating in the GWTG initiative. This improving trend was accompanied by noteworthy decrease variability in D2B times over time between these institutions. Importantly, this translated in higher proportion of patients receiving primary PCI in compliance with the D2B standard of ≤90 minutes set by the ACC/AHA guidelines. Despite this, our data also show that elderly people, women, and minorities have the greatest delay in the D2B times as compared with younger patients, men, and whites, respectively, even after accounting for other comorbid conditions. Although our investigation suggests that institutions participating in GWTG programs had increased the proportion of patients with D2B time ≤90 minutes by 22.6% over the last 5 years, the disparity between whites and nonwhites, between ARTICLE IN PRESS American Heart Journal Month Year 6 Mehta et al Figure 4 Median D2B times by age, sex, and race. Figure 5 Proportion of patients with D2B time ≤90 minutes by age, sex, and race. younger and older patients, and between men and women persisted. Comparisons with prior studies Multiple observational studies have reported the D2B times for patients undergoing primary PCI.16-18 These studies have shown a wide variation in this timing. For example, in the patients enrolled in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events at sites across 6 continents between 1999 and 2004, the median D2B time was 78 minutes (IQR 47-120 minutes).16 The National Registry of Myocardial Infarction investigators reported a much longer median D2B time of 111 minutes (IQR 84-152 minutes) for patients in the United States (like in the ARTICLE IN PRESS American Heart Journal Volume 0, Number 0 Mehta et al 7 Table IV. Proportion of patients with D2B time ≤90 minutes by age, sex, and race over calendar years Calendar year Category 2002 (%) 2003 (%) 2004 (%) 2005 (%) 2006 (%) Age ≥65 Age b65 Female Male Minority White 27.19 42.42 33.33 37.14 11.11 36.63 39.93 45.84 38.41 45.53 36.44 44.23 40.21 43.39 38.10 43.90 35.75 43.67 37.48 46.61 38.69 45.13 33.42 45.40 44.66 55.79 45.80 53.95 44.01 53.04 GWTG program) enrolled between 1994 and 2000.17 Investigators from the German Maximal Individual Therapies for Acute Myocardial Infarction and Myocardial Infarction Registry noted a very short median D2B time of 70 minutes (IQR 45-132 minutes) for patients enrolled between 1994 and 1998.18 Despite this wide variation in D2B times, most registries that have tracked D2B time trends over time have shown encouraging trends toward significant reduction in this timing. For example, median D2B time decreased by 23 minutes (from 98 to 75 minutes) in GRACE between 1999 and 200419; by 13 minutes (from 117 to 104) in NRMI between 1994 and 200014; and by 17 minutes (from 84 to 67 minutes) in the Maximal Individual Therapies for Acute Myocardial Infarction and Myocardial Infarction Registry between 1994 and 1998.18 Our findings from the GWTG are consistent with these reports. Our data also confirm that more and more patients are receiving primary PCI in ≤90 minutes. Thus, the increasing emphasis on health care quality and efforts by government, professional societies, health maintenance organizations, insurance companies, and payers; the public reporting of performance measures; and the growing awareness in general public regarding this subject perhaps have been successful in stimulating institutions in implementing process changing, allowing them to overcome multiple barriers that limit timely reperfusion and have contributed significantly to this better trend. In addition, the new ACC/AHA STEMI guidelines published in August of 2004 4 suggested a lower D2B time of ≤90 minutes as compared with D2B ≤120 minutes in the guidelines published earlier in 1999. Because the ACC/AHA guidelines are regarded as gold standard for evidence-based practice by the cardiology community, the change in emphasis to a lower D2B time in recent iteration of these guidelines could also have significantly contributed to the decreasing D2B times as well as the increase proportion of patients receiving primary PCI within 90 minutes of their arrival to the emergency department. As observed in our study, elderly people, women, and minority populations have been consistently shown to have greater delay in D2B times as compared with their Table V. Adjusted estimates of compliance with D2B time ≤90 minutes in subgroups Subgroups ⁎ OR 95% CI P Age ≥65 vs b65 y Female vs male Minorities vs whites 0.815 0.836 0.760 0.735-0.903 0.763-0.916 0.686-0.842 b.0001 b.0001 b.0001 ⁎ P for interaction between age, sex, and race and calendar quarter on D2B time ≤90 minutes >0.1 for all. peers.17,20 Thus, individuals with these characteristics are at ‘double jeopardy’ because they are also less likely to receive any reperfusion and other evidence-based therapies.21 Elderly people, women, and minorities have been also shown to be at higher risk for worse outcome after STEMI.22-24 Previous investigations have shown that delay in treatment, that is, longer D2B times, have a much greater impact on outcomes in patients at high-risk as compared with those at low-risk.25 Better understanding of the reason(s) for these features to be associated with poorer care and longer D2B times is therefore imperative. This may allow institutions to design and target specific strategies in these at-risk cohorts that may eventually improve compliance with the D2B benchmark set by national guidelines, over all use of evidence-based treatments and outcomes in these high-risk patients. Opportunities for further improvement Although there has been a decrease in D2B times accompanied by a reduction in variability in this time across sites over time and an increase in the proportion of patients with D2B times ≤90 minutes at participating institutions in the GWTG initiative, potential for further improvement remains. The decrease is at best modest, and considerable variability continued to exist among sites. By the end of the study period, the median D2B time was just less than the ≤90-minute benchmark, with only 58% of patients treated within this period. The ‘gap’ was even greater for elderly people, women, and minorities as compared with their peers despite adjustment for baseline confounders including insurance status. Finally, most troublesome was the fact that the disparity in the time to treatment in these subgroups as compared with their peers persisted over time. In lieu of the close link between D2B times and outcomes,2,3 these findings call for a need to promote process changes that specifically focus on reducing the delay in rapid institution of primary PCI. The literature is replete with many approaches for improving D2B times, and some have been more successful than others in improving this performance metric.7 Institutions should adopt and/or customize specific tools and processes that best suit the local culture and allow for greater buy-in of their caregivers for maximizing their impact on D2B times. ARTICLE IN PRESS 8 Mehta et al Limitations Similar to prior investigations that have evaluated trends in treatments of patients with acute myocardial infarction, we lack a control group. Thus, the possibility that the observed trend in improvement of the D2B times may be related to a natural progression toward overall better adherence to evidence-based therapies and better guideline compliance including decreasing delays in D2B time with exposure to program initiative over time cannot be entirely ruled out. Participation in GWTG was voluntary; therefore, these findings may not be applicable to institutions that do not demonstrate interest in tracking and improving their quality and outcomes. Finally, we cannot provide any insight on the costeffectiveness of such large-scale quality improvement initiatives. We do not have information on the mode of transport, that is, via emergency medical services or self, or on detailed hospital and cardiac catheterization specific variables. Thus, we are unable to determine the influence of these factors on D2B time. Conclusions The median D2B times with primary PCI have improved modestly in hospitals participating in the AHA GWTG program over the last few years but remain below ideal levels. The D2B times are particularly delayed in elderly people, women, and minority populations and have persisted to remain longer over time in these cohorts as compared with younger patients, men, and whites. These results indicate significant opportunities for improvement and the need for ongoing efforts on the part of health care institutions to develop internal systems and/or to voluntarily participate in national myocardial infarction quality improvement initiatives such as the D2B Alliance or the AHA's ‘Mission: Lifeline’ Initiative designed to improve D2B times. References 1. Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomized trials. Lancet 2003;361:13-20. 2. Cannon CP, Gibson CM, Lambrew CT, et al. Relationship of symptomonset-to-balloon time and door-to-balloon time with mortality in patients undergoing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2000;283:2941-7. 3. De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Ottervanger JP, et al. Time delay to treatment and mortality in primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: every minute of delay counts. Circulation 2004;109:1223-5. 4. Antman E, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). Available at http://www.acc.org/clinical/ guidelines/stemi/index.pdf; 2004 [Accessed July 12, 2007]. American Heart Journal Month Year 5. Rogers WJ, Dean LS, Moore PB, et al. Comparison of primary angioplasty versus thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1994;74:111-8. 6. Curtis JP, Portnay EL, Wang Y, et al. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction–4. The pre-hospital electrocardiogram and time to reperfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction 2000-2002 findings from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction–4. (NRMI-4). Am J Cardiol 2006;47:1544-52. 7. Nallamothu BK, Bates ER, Herrin J, et al. Times to treatment in transfer patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States: National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI)– 3/4 analysis. Circulation 2005;111:761-7. 8. McNamara RL, Wang Y, Herrin J, et al. Effect of door-to-balloon time on mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:2180-6. 9. Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang Y, et al. Strategies for reducing the door to balloon time in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2308-20. 10. LaBresh KA, Glicklich R, Liljestrand J, et al. Using Get With The Guidelines to improve cardiovascular secondary prevention. Joint Comm J Quality Saf 2003;29:539-50. 11. LaBresh KA, Tyler PA. A collaborative model for hospital-based cardiovascular secondary prevention. Q Manag Health Care 2003;12:20-7. 12. LaBresh KA, Ellrodt AG, Glicklich RG, et al. Get With the Guidelines for cardiovascular secondary prevention: pilot results. Arch Int Med 2004;164:203-9. 13. D2B: an alliance for quality—a Guidelines Applied in Practice Program. Available at www.d2balliance.org [Accessed July 12, 2007]. 14. Jacobs AK. Regional systems of care for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: being at the right place at the right time. Circulation 2007;116:689-92. 15. Available at http://www.accncdr.com/WebNCDR/NCDRDocuments/datadictdefsonlyv30.pdf [Accessed November 28, 2007]. 16. Nallamothu BK, Fox KAA, Kennelly BM, et al. Relationship of treatment delays and mortality in patients undergoing fibrinolysis and primary percutaneous coronary intervention. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Heart 2007;93:1552-5. 17. Angeja BG, Gibson CM, Chin R, et al, for the participants in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2-3. Predictors of door-to-balloon delay in primary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol 2002;89:1156-61. 18. Zahn R, Schiele R, Schneider S, et al. Decreasing hospital mortality between 1994 and 1998 in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty but not in patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis-results from the pooled data of the Maximal Individual Therapy in Acute Myocardial Infarction (MITRA) and the Myocardial Infarction Registry (MIR). J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:2064-71. 19. Stenestrand U, Lindback J, Wallentin L, for the RIKS-HIA Registry. Long-term outcome of primary percutaneous coronary intervention vs. prehospital and in-hospital thrombolysis for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA 2006;296:1749-56. 20. Eagle KA, Nallamothu B, Mehta RH, et al. Trends in acute reperfusion therapy for ST-elevation myocardial infarction from 1999 to 2004: We're getting better but we have a long way to go. Eur Heart J (in press). 21. Zahn R, Vogt A, Zeymer U, et al. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitender Kardiologischer Krankenhausärzte. In-hospital time to treatment of patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction treated with ARTICLE IN PRESS American Heart Journal Volume 0, Number 0 primary angioplasty: determinants and outcome. Results from the registry of percutaneous coronary interventions in acute myocardial infarction of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitender Kardiologischer Krankenhausarzte. Heart 2005;91:1041-6. 22. Eagle KA, Goodman SG, Avezum Á, et al, for the GRACE Investigators. Practice variation and missed opportunities for reperfusion in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: findings from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Lancet 2002;359:373-7. 23. Mehta RH, Harjai KJ, Cox DA, et al. Comparison of coronary stenting versus conventional balloon angioplasty on 5-year Mehta et al 9 mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2005;96:901-6. 24. Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, et al, for the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Participants. Sex-based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1999;341: 217-25. 25. Mehta RH, Marks D, Califf RM, et al. Differences in the clinical and angiographic features and outcomes in African American and Caucasians with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med 2006;119: 70e1-8.