TSG Status Report # 3

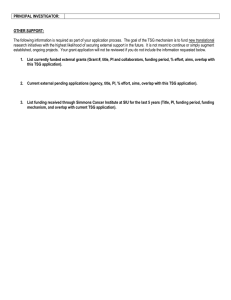

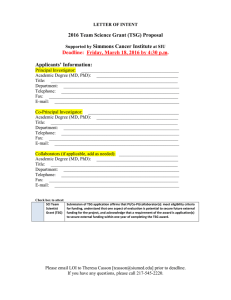

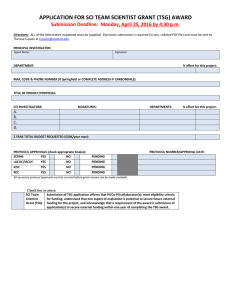

advertisement