Engaging the Nonprofit Workforce - The Georgia Center For Nonprofits

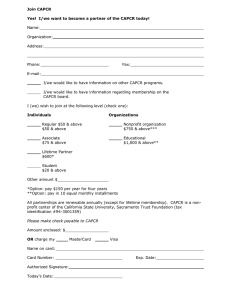

advertisement