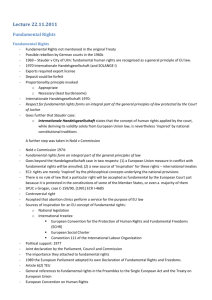

The position of aliens in relation to the European Convention on

advertisement