355

NeuroRehabilitation 26 (2010) 355–368

DOI 10.3233/NRE-2010-0573

IOS Press

Perspectives on evidence based practice in

ABI rehabilitation. “Relevant Research”:

Who decides?

Catherine Wiseman-Hakes a,∗, Sheila MacDonaldb and Michelle Keightleyc

a

Graduate Department of Rehabilitation Science and Department of Speech Language Pathology, University of

Toronto, Canada

b

Sheila MacDonald & Associates, Toronto, Canada

c

Graduate Department of Rehabilitation Science, & Department of Psychology, University of Toronto, Canada

Abstract. Growing evidence suggests that acquired brain injury (ABI) rehabilitation and research should be guided by a philosophy

that focuses on: restoration, compensation, function and participation in all aspects of daily life. Such a broad, more pluralistic

approach influences ABI rehabilitation research at a number of levels, including both the generation of evidence, and in searching

for, critiquing and applying the evidence to practice. The objective of evidence based medicine/practice (EBM/EBP) is to

apply and integrate clinical expertise with evidence gained through systematic research and scientific inquiry to medical/clinical

practice. While there is abundant literature debating the practical and sociological implications of EBP, there has been limited

examination of EBP within the inherently complex nature of ABI rehabilitation and rehabilitation research. This paper provides a

framework for clinical decision making regarding evidence based practice in the context of ABI rehab including: 1. A discussion

of the purpose of evidence based practice, 2. Levels of evidence relevant to ABI rehabilitation research, and 3. A rationale

for incorporating a broader, more pluralistic concept of evidence or “person-centred EBP”. We conclude with a series of key

questions for the evaluation and application of systematic reviews of the evidence in the context of ABI rehabilitation.

Keywords: Acquired brain injury rehabilitation, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation, evidence based practice, evidence based

medicine, rehabilitation research, treatment evidence, outcome, intervention

1. Background and introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI), is defined as an injury

to the brain occurring after birth that is not related to

congenital defect or degenerative disease. Causes of

ABI include (but are not limited to) hypoxia, illness,

infection, stroke, substance abuse, toxic exposure, trauma, and tumor [3]. Although there is a lack of clarity

regarding the definition of ABI internationally, for the

purposes of this paper, ABI includes traumatic brain

injuries (TBI), strokes, brain illness, and any other kind

∗ Address for correspondence: Catherine Wiseman-Hakes, M.Sc.

Ph.D. (candidate), Graduate Dept. of Rehabilitation Science, University of Toronto, 160-500 University Ave., Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M5G 1V7. Tel.: +1 416 946 8575; Fax: +1 416 946 8570; E-mail:

catherinew.hakes@utoronto.ca.

of brain injury. ABI may cause temporary or permanent impairment in such areas as cognitive, emotional, metabolic, motor, perceptual motor and/or sensory

brain function [3]. The most common type of ABI is

TBI, which is defined as an acquired injury to the brain

due to applied force, and includes closed head injury

(e.g. via gravitational force) and open head injury (e.g.

with penetration of the skull by a missile [52] TBI;)

is a leading cause of death and disability world-wide.

Injuries to the brain are among the most likely to result

in death and permanent disability [27].

An individual with ABI may experience a variety

of cognitive, communication, physical, emotional, social and psychological difficulties. These difficulties

can create profound disruption and challenges for both

the individuals and their families, making return to independent living in the community a primary focus.

ISSN 1053-8135/10/$27.50 2010 – IOS Press and the authors. All rights reserved

356

C. Wiseman-Hakes et al. / Perspectives on evidence based practice in ABI rehabilitation

Successful community integration, or in effect one’s

quality of life, typically involves regaining a sense of

‘self’, relationships with others, independence in one’s

living situation and activities to fill one’s time [34,39].

This goal has been reflected in the increasing number

of publications focused specifically on quality of life

after brain injury [15,34,39,50,59].

Growing evidence suggests that ABI rehabilitation

and research should be guided by a philosophy that focuses on: restoration, compensation, function and participation in all aspects of daily life, including consideration of contextual factors, the unique life circumstances of the individual, and the quality of support

provided by others [5,61,64]. This philosophy has a

direct impact on the way that evidence for intervention

is both generated for, and applied in, clinical decision

making for ABI rehabilitation. Additionally, this philosophy has led to the call by some researchers and

clinicians for a broader and more “pluralistic” approach

to evidence based practice (EBP). The term ‘pluralistic

approach’ was first identified in the nursing literature

on EBP [35]. In the context of ABI rehabilitation, it

is an approach that considers the whole person, their

daily life contexts, and supports, and thus, should be

reflected within evidence generation, evidence search,

and knowledge translation [5,31,35,37,63,64]. Taken

in its literal sense, a pluralistic approach is one in which

there is more than one universally accepted doctrine or

methodology. When this pluralistic approach is applied

to ABI rehabilitation and rehabilitation research, it is

one which advocates for a broader, more inclusive definition of individualized, client centred treatment and

thus a broader scope of research methodology.

2. Goals and objectives of paper

A broader, more pluralistic approach to ABI rehabilitation influences ABI rehabilitation research at a number of levels, including both the generation of evidence,

as well as in searching for, critiquing and applying the

evidence to practice. While there is abundant literature

debating the practical and sociological implications of

EBP, there has been limited examination of EBP within the inherently complex nature of ABI rehabilitation

and rehabilitation research. Thus, we aim to provide a

framework for clinical decision making regarding evidence based practice in the context of ABI rehabilitation. Included will be: 1. A discussion of the purpose of evidence based practice and some of the challenges associated with implementing EBP in ABI re-

habilitation, 2. Levels of evidence relevant to ABI rehabilitation research, and 3. A rationale for incorporating a broader, more pluralistic concept of evidence or

“person-centred evidence based practice”. Finally, we

will present a series of key questions for the evaluation

and application of systematic reviews of the evidence

in the context of ABI rehabilitation, and very briefly,

summarize considerations that clinicians can use to determine and critically analyze the evidence. It is our

hope that a critical appraisal of evidence summarized

in systematic reviews, utilizing specific criteria within

a pluralistic approach to EBP [35], will facilitate sound

clinical decision making and ultimately ensure the most

effective rehabilitation for individuals with ABI. At a

minimum, we hope this paper may stimulate further

discussion regarding the generation and application of

evidence in the context of client-centred care in ABI

rehabilitation.

3. Evidence based medicine and evidence based

practice; what is it?

Evidence based medicine (EBM) is defined as the

conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best

evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients [46]. The objective of EBM is to apply and integrate clinical expertise and judgment with

evidence gained through systematic research, and scientific inquiry to medical/clinical practice, and to improve health outcomes through the implementation of

the most effective interventions [4,23]. Over time, the

principles of EBM have been extended to a broader

rubric of evidence based practice (EBP) which addresses clinical practice in rehabilitation [37]. According to

Sackett et al. [45] EBM (with application to EBP) is

concerned with a) the scientific processes involved in

amassing empirical support for population statements

of the form “TX” (some treatment) that is effective or

efficacious for “P” (some population), and then b) using

these statements to guide the delivery of specific clinical services to specific patients. Those practicing EBM

and EBP seek to assess the quality of evidence relevant

to the risks and benefits of treatment(s), (including lack

of treatment), with the ultimate goal of “best” practice. In the current culture of health care and practice,

“best” refers to evidence that is derived from scientific

research, based on carefully executed randomized controlled trials, the apex of the ‘evidence hierarchy’ and

the gold standard for meeting EBM (and EBP) criteria

for validity. However, despite the best intentions of

C. Wiseman-Hakes et al. / Perspectives on evidence based practice in ABI rehabilitation

policy makers and clinicians, and the growing amount

of scientific literature specific to ABI rehabilitation [10,

43]. EBP in the context of ABI rehabilitation is fraught

with challenges. This may be due in part to the fact

that the label of “ABI,” is one of the most challenging

to categorize based on diagnosis, as it can result in a

myriad of diverse and complex clinical presentations.

4. The challenge of applying evidence to practice

in ABI rehabilitation

The application of evidence to clinical practice requires academic and clinical expertise, as well as additional expertise in the retrieval, interpretation and application of scientific studies. This can be a daunting

task for busy clinicians for a number of reasons; there

may be issues within the hospital/rehabilitation system

and culture, such that heavy case loads, the pressure

to see more clients/patients, little or no protected time

to search the literature, as well as little or no protected time or funding for continuing education opportunities in the area of evaluating evidence and EBP, may

(and often does) result in little time being attributed

to this important topic. Furthermore where education

does take place, it is often based on a rigid definition

of evidence.

In fact, as early as 1971, Garvey and Griffith [21]

stated that “the individual scientist (and clinician) is

. . . overloaded with scientific information, and (can)

no longer keep up with and assimilate all the information being produced that (is) related (and relevant to)

his primary specialty,” (p. 350). Additionally, as the

number of studies evaluating the effects of treatment

interventions in ABI continues to grow, difficulties can

arise when different studies reach different conclusions

as to the merits of a particular intervention. Further,

there have been a number of well documented criticisms of EBM, some of which apply directly to EBP for

ABI rehabilitation, from the perspectives of science, social science, philosophy and ethics [23,35,37,38,54,55,

64]. The reality of clinical practice is, as described by

Schön [47], “messy, complex and enmeshed in ethical

conflict. Practice is contextually located and embedded in multiple cultures that are created and re-created

by ‘actors’ in that context”(p. 91). While Sch ön [47]

was not writing specifically about rehabilitation, it is

directly applicable to and reflective of the complexities

of ABI rehabilitation (and thus rehabilitation research)

which are influenced by such factors as the heterogeneity of the population, difficulties with prognostication

357

based on the diagnosis, and variations in patterns of

presentation and recovery, motivation of the individual,

and the support systems available to them. Emotional sequelae including depression, anxiety and loss of

sense of self [39,43], among others, can contribute to

social problems following ABI and this, coupled with

any number of cognitive, communication, behavioural

and physical difficulties can result in social isolation.

In summary, there are a number of challenges associated with the process of implementing EBP in ABI rehabilitation, which include: defining the problem, conducting an efficient search to locate the best evidence,

critically appraising the evidence, and applying it in the

context of clinical care [32,54].

5. Meeting the challenges of evidence based

practice

Given these challenges, Furlan et al. [20] suggest

that a systematic review, (i.e., a synthesis of relevant

research in the form of an evidence based literature review), can be an invaluable tool for frontline clinicians,

policy makers, and those responsible for the development of practice guidelines, who seek to keep abreast of

current findings regarding treatment interventions. According to Furlan et al. [20] a systematic review should

resolve any conflicts regarding differing research conclusions by “employing explicit methods to search, select, critically appraise and combine all available primary studies on a pre-specified topic, thereby making

objective recommendations about the effects of these

interventions” (p. 209).

However, according to Kunz [29], clinicians, policy

makers and guideline developers “rightly expect guidance from methodologists in the use and interpretation

of those studies (and research synthesis review papers)

and their integration of those studies into guideline recommendations,” (p. 207). Further, if the definition of

a systematic review is contingent upon the term “relevant research”, the question remains, how do we operationalize what qualifies as relevant research and who

should be making those decisions? These questions

have also been raised by Upsher [53], where he noted

the shift to dissemination of digested information such

as Cochrane abstracts or publications such as EvidenceBased Medicine. He added that “while this is laudable

in many ways, it raises important questions concerning who has the authority to create, interpret and judge

evidence,” (p. 95). Thus, clinicians need a consistent

method to: 1. Analyze the quality of the review, 2. De-

358

C. Wiseman-Hakes et al. / Perspectives on evidence based practice in ABI rehabilitation

termine if the evidence presented and the conclusions

of the reviewers actually match the clinical profile of

their patient/client and the clinical issue in question,

and 3. Determine if the research evidence is consistent

with the goals of facilitating restoration, compensation,

functioning, activity and participation in all aspects of

daily life.

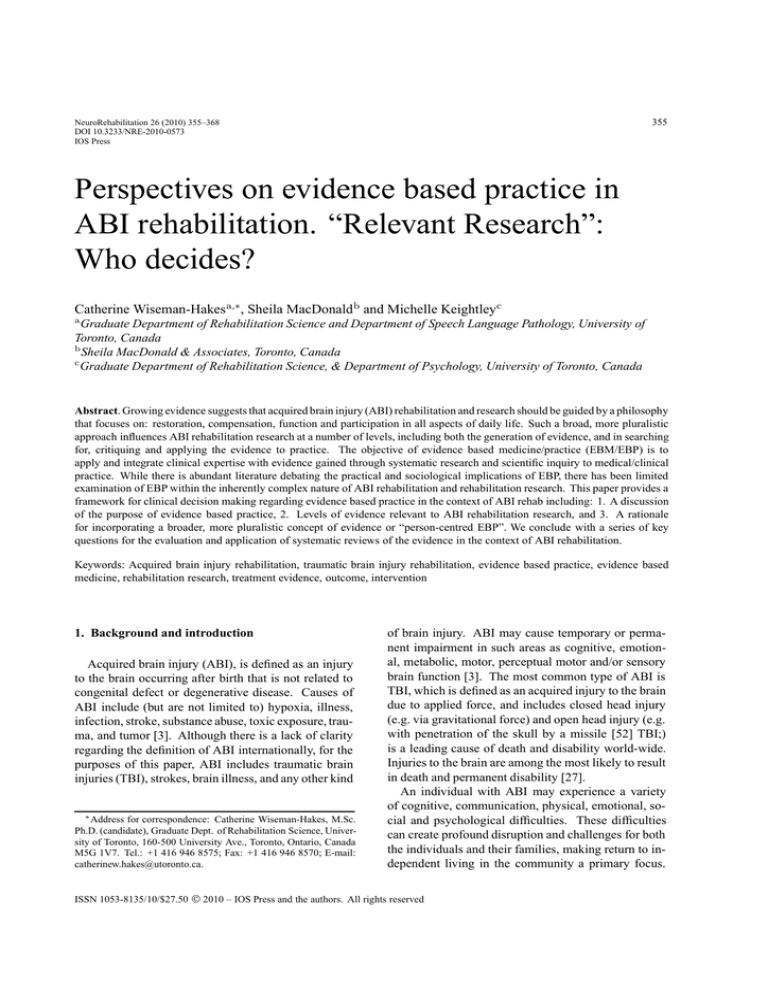

Table 1

A Taxonomy of literature reviews [11,12].

Cooper, Harris and Larry V. Hedges. Table 1, “A

Taxonomy of Literature Reviews.” In The Handbook

c 1994 Russell Sage Founof Research Synthesis. dation, 112 East 64th Street, New York, NY 10021.

Reprinted with permission

Characteristic

Focus

Categories

Research outcomes

Research methods

Theories

Practices or applications

Goal

Integration

a) Generalization

b) Conflict resolution

c) Linguistic bridge building

Criticism

Identification of central issues

Perspective

Neutral representation

Espousal of position

Coverage

Exhaustive

Exhaustive with selective citation

Representative

Central or pivotal

Organization

Historical

Conceptual

Methodological

Audience

Specialized scholars

General scholars

Practitioners or policy makers

General public

6. Interpreting the evidence for EBP

6.1. The systematic review: What is it exactly (and

why should we care?)

The reality is that clinicians engaged in patient care,

and policy makers involved in the development of

guidelines and budgeting, do not have time to be expert reviewers of all available evidence in all areas of

intervention. Therefore, the most practical resource is

to turn to systematic reviews. A systematic review is

a literature review focused on a single question which

tries to identify, appraise, select and synthesize research

evidence relevant to that question, and most (all though

not all) are restricted to including high quality levels of

evidence according to pre-determined criteria defining

levels of evidence. Thus, systematic reviews are generally regarded as the highest level of medical evidence

by EBM professionals. An understanding of systematic reviews and how to interpret and apply them in

practice is becoming mandatory for all professionals

involved in the delivery of health care.

However, systematic reviews, even those on the same

topic, can vary greatly on many levels. There can be

differences in the scope and quality of reviews from the

perspective of: 1. The types or levels of evidence included, 2. The methodology and framework (which can

dictate or influence the meSH terms) used in the gathering and interpretation of evidence, and 3. The translation and application of evidence, given the unique

complexities and the contexts of individual client care

in ABI rehabilitation [32]. In 1988, Cooper [11, as

cited in 12] presented a taxonomy that classifies literature reviews based on 6 characteristics (Table 1).

These include: focus of attention, goal of the synthesis,

perspective on the literature, coverage of the literature,

organization of presentation and intended audience.

These characteristics can also be applied to systematic reviews of the literature.

We argue that as responsible clinicians and scientists,

we need to consider the issues raised by Coopers’ model

when applying the results of a systematic review to our

own clinical practice in acquired brain injury. In order

to do this a number of questions must be asked:

– Is the focus of the review under consideration specific to a sub group of individuals with ABI (example TBI or stroke) or broadly to the heterogenous

population of ABI? Does it focus on acute care or

community interventions? Do the studies include

long term follow up of subjects or immediate results from interventions recently applied? Are

there other considerations addressed such as implementation issues (cost, time, level of expertise

required for intervention), social validity of the

intervention and outcome?

– What is the defined goal of the systematic review

and is it consistent with the needs of the clinician?

This is important, as even the terminology used

in the search strategies may differ depending on

the goal. For example, a review of interventions

for vegetative state might differentiate terms such

as “minimally responsive”, “coma” or “vegetative

state”. Conversely, a review designed to identify issues in severe trauma might have a goal of

identifying the many interventions available to this

population. Thus searching the literature to answer the clinical question, “Does coma intervention work?” would necessitate some interpretation

C. Wiseman-Hakes et al. / Perspectives on evidence based practice in ABI rehabilitation

of the evidence and the goal of article selection

applied to related systematic reviews.

– The perspective of the reviewers is also a very important consideration. While objectivity is a desirable goal, analysis of data without a clear understanding of the conceptual framework or terminology for a specific field could lead to errors or

omissions in article selection [32]. Reviews conducted by those who are knowledgeable about a

given field are more likely to include the breadth

and depth of search required. However, a review

of interventions after TBI conducted by experts in

stroke may apply an incorrect conceptual framework to the process, thus omitting important evidence and reporting incorrect conclusions.

– Finally, issues regarding the coverage or depth of

content being reviewed are an important consideration. For example, cognitive rehabilitation may

include interventions for communication or conversely a review of communication interventions

might benefit from inclusion of studies of cognitive interventions. The coverage and depth of a

systematic review must be taken into consideration

particularly if interventions have evolved since the

review was conducted, if new interventions have

been generated, or if terminology has expanded to

increase the scope of an area. For example, a term

such as “behaviour management” may well have

encapsulated all related treatment articles historically; yet new considerations of self regulation or

executive control have expanded the scope of these

interventions. Thus, consideration of the scope or

framework and goals and objectives of the systematic review in question is essential for clinicians

as they appraise the conclusions of the authors,

and the applicability of the evidence to their own

clinical practice.

6.2. Levels of evidence

It is also necessary to consider the levels of evidence

included in the review.

Table Ib) Classification of evidence: In North

America, the most commonly used and accepted classification system is the one by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [56] for ranking evidence about the

effectiveness of treatments or screening:

– Level I: Evidence obtained from at least one properly designed randomized controlled trial.

– Level II-1: Evidence obtained from well-designed

controlled trials without randomization.

359

– Level II-2: Evidence obtained from well-designed

cohort or case-control analytic studies, preferably

from more than one center or research group.

– Level II-3: Evidence obtained from multiple time

series with or without the intervention. Dramatic

results in uncontrolled trials might also be regarded

as this type of evidence.

– Level III: Opinions of respected authorities, based

on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees.

There is no one specific citation for the inclusion of

Single Subject Designs (SSD’s) or Qualitative Designs in the evidence hierarchy. Single subject design

is an important and predominant inclusion in the ABI

rehabilitation evidence literature [32,63]. Qualitative

designs also play an important adjunct role in the ABI

rehabilitation evidence literature, as they provide important evidence to answer “ how ” or “ what ” questions and to explore, explain or describe a phenomenon

or experience from the perspective of the research participants [13,36]. Single subject designs should be considered in any systematic review. Qualitative studies

can also be of value for clinicians reviewing the ABI

rehabilitation literature as they can elucidate that individual narratives vary greatly and meaning plays an

important role in recovery. Both single subject designs

and qualitative literature are often included as Level III

evidence, which is consistent with that used in many

health-related evidence reviews [6,7,42,63,66].

Level I evidence, in the form of randomized controlled trials (RCT’s) is widely considered by methodologists and scientists to be the “gold standard”, in

other words, the most reliable, most free of bias and

valid method of determining the effects of a particular

form of rehabilitation, treatment or intervention for a

defined clinical population [29]. Many systematic reviews use inclusion criteria for evidence that is limited

to the RCT and a few other high level studies. For

example, Chestnut et al. [8] completed a summary report of evidence for the effectiveness of rehabilitation

for persons with traumatic brain injury. To complete

this report, they reviewed over 3000 abstracts, and the

“strongest studies” were critically appraised, and the

data placed in evidence tables. They concluded that “a

commitment must be made to population based studies,

a strong controlled research design, standardization of

measures, adequate statistical analysis, and specification of health outcomes important to persons with TBI

and their families” (p. 176). Although levels of evidence other than RCT’s are sometimes described within

an EBM framework, they are often given little weight.

360

C. Wiseman-Hakes et al. / Perspectives on evidence based practice in ABI rehabilitation

However, in some domains relevant to the field of ABI

rehabilitation such as special education, SSD research

is highly regarded as a potential basis for judgments

about EBP [26,40,63]. Thus, consideration and analysis of other types of evidence in ABI rehabilitation is

important for a number of reasons. In the sections to

follow we will discuss whether sole reliance on RCT’s

is sufficient and make a case for inclusion of SSD’s as

well as other forms of evidence.

7. Limitations of the RCT in the context of ABI

rehabilitation

In their paper “Reflections on evidence based-practice and rational clinical decision making”, Ylvisaker

et al. [64,65] point out that RCT’s, or indeed, clinical

experiments of all types, however desirable they are

in the context of responsible clinical practice, do not

exhaust the considerations relevant to scientific clinical

decision making. Further, there are a number of well

documented limitations in relying solely on RCT’s that

are highly relevant to ABI rehabilitation, particularly as

the results of an RCT are typically applied to a population, rather than an individual, and the two are not necessarily synonymous. Montgomery and Turkstra [37]

report that an overemphasis on RCT’s (Level 1 evidence) often results in skepticism when this standard is

not attained, yet they conclude that “ In the treatment

of each individual patient, judgment must be used to

some degree, and this requires the use of reason based

on information extrinsic to the results of RCT’s”. They

report that this is inescapable, and that it is the ability

to make those judgments that makes a clinician (p. X).

Montgomery and Turkstra [37] present three arguments

for caution when interpreting the evidence:

1. “Statistically significant is not synonymous with

clinically significant”; the determination of what

constitutes both “statistical significance” and a

“clinically meaningful result” is a social judgment.

2. Judgment is always required in the case of an

individual patient.

3. RCT’s may be either impractical (if not impossible) or inappropriate for answering many important clinical questions.” (p. X).

For research in the field of ABI, particularly in some

areas of rehabilitation such as cognition, communication, behaviour, activities of daily living and community reintegration, it is not always practical or appropriate

to rely solely on the RCT as the gold standard. There

are numerous difficulties and limitations in applying

this model to such a heterogeneous and complex population. Mykhalovsky and Weir [38] caution against the

standardization of clinical judgment and clinical care.

Kennedy and Turkstra [28] further analyze a number of the limitations of relying on high levels of evidence, particularly the RCT. First, with large sample

sizes, group heterogeneity may mask individual treatment benefits. Often, there are differences at baseline,

such that each subject’s profile may not be equivalent.

Next, blinding of clinician raters and study participants

as to group assignment may be impractical. Random

assignment does not necessarily mean that all groups

will be equal on important variables. Recruitment and

drop out rates may be beyond the researcher’s control

in a treatment study that extends over several weeks,

particularly when participants are trying to return to the

community or school. Additionally, as Ylvisaker [63]

points out, “The individuals (with ABI) most in need

of long term clinical and special education services

are often those excluded from, or are outliers in, clinical trials, (e.g., individuals with serious behavioural

challenges or psychiatric diagnoses, co-existing or preexisting impairments such as learning disabilities or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, unusual life circumstances and the like),” (p. 211).

There are a number of factors unique to ABI which

researchers, authors of systematic reviews, and clinicians should consider when generating, synthesizing,

and applying the evidence to clinical practice. First,

due to the considerable heterogeneity in the ABI population, patient characteristics over and above a diagnosis of ABI and level of severity should be considered.

Further, this heterogeneity necessitates that interventions for communication, cognition, behaviour, vocational rehabilitation etc. be individualized depending

on a number of equally important criteria including:

the person’s stage of recovery, their unique communication/cognitive, physical, psychological and emotional and behavioural profile, the person’s goals, treatment location, the competence and needs of relevant

support people, training and competence of the treating clinicians (i.e. expertise in ABI), available time

and funding and compliance, in addition to the varying

cognitive and communication demands of home, work,

or school [9,32,63]. While in earlier studies, severity

of injury was used to equate experimental samples, it

is now recognized that consideration of the cognitive,

communication and behavioural profiles is necessary

when comparing subjects [28,32]. To rely solely on

C. Wiseman-Hakes et al. / Perspectives on evidence based practice in ABI rehabilitation

a diagnosis of moderate-severe ABI is erroneous, as

there can be many different presentations and needs

that accompany this complex designation [66]. The

desired outcome of the treatment protocol and the outcome measurement must also be considered from the

perspective of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and

Health [61]. Does the measure assess outcome from the

perspective of disability (including body function and

structure) or activity and participation in the context of

environment, the latter in keeping with a desired long

term goal of community reintegration. Contextualization of the intervention to meet the unique life demands

of the individual is also strongly advocated for in ABI

rehabilitation [22,63].

8. Other types of evidence in ABI rehabilitation

research: Beyond the RCT

A primary limitation of systematic reviews of the literature for ABI rehabilitation which rely on a narrow

definition of evidence (i.e. the RCT with a few other lower level studies) is that they typically conclude

that the evidence to support rehabilitation in specific

areas is limited, and the reader is left to draw their

own conclusions. As a result, an ethical dilemma is

created when funding sources use these conclusions

to deny services. In 2006, Perdices et al. [41] conducted a review of 1298 empirical studies indexed in

a web-based resource for brain injury research called

PsycBITETM . They found that the largest proportion of rehabilitation studies were single subject design (39%), followed by case series (22%), randomized control trials (21%), non-randomized control trials (11%) and systematic reviews (7%). Most reports were concerned with stroke (41%) traumatic brain

injury (29%) and Alzheimer’s and related dementias

(22%). The most frequently investigated deficits were

communication/language/speech disorders (24%); independent self-care activities (19%) behaviour problems (17%); memory impairments (17%), and anxiety; depression, and stress adjustment (15%). After

rating the studies for methodological quality, Perdices

and colleagues [36] concluded that the methodological

quality of RCT’s across the spectrum of TBI research

was modest overall and they presented many reasons

for this which concurred with those of Kennedy and

Turkstra [28] outlined above.

Single Subject Design (SSD) tends to be the predominant model of intervention research for this pop-

361

ulation, not because large randomized control studies

are a novel concept in rehabilitation but because the

complexities and interplay of human communication,

cognition, emotion and behaviour, ABI, and individual

circumstances combine to make single subject design

more applicable to a wider variety of treatment circumstances [28,41,63]. Perdices et al. [41] presented the

advantages of single subject design studies and asserted that sophisticated (experimental) SSD’s incorporating, among other things, multiple baselines across subjects, as well as randomization of the order of active

treatment phases, can potentially provide a level of evidence comparable to that of RCT’s. In fact, should a

clinician be researching interventions for an individual that closely resembles the profile of the subject in

a successful SSD, then it may be more clinically rational and responsible to choose the SSD intervention

(Class III evidence) than an intervention guided by a

population based evidence statement (Class I evidence,

RCT) [63]. This is, however, in contrast to a case study

design which is less rigorous (i.e. uncontrolled) and

thus is less reliable as a source of evidence than an intervention study. For these reasons many researchers

of cognitive-communication, behavioural and community based interventions caution that strict adherence

to a preordained experimental model such as RCT’s

as a filter to accept or reject particular clinical practices in the highly diverse ABI population may result

in unsuccessful generalizations from research to treatment outcomes [41,49,64,65]. This is consistent with

the opinions of Kunz [29] expressed in her recent editorial, where she states that “while most methodologists continue to maintain that treatment effects coming from RCT’s are-in principle, far better protected

against bias than non RCT’s and therefore, deserve a

higher credibility than estimates of treatment effects

generated from non RCT’s, there are at the same time,

a dissenting group of methodologists who dispute the

claim of RCT ascendance in similar clinical issues that

demonstrate similar treatment effects, at least based on

high-quality observational studies” (p. 207). Thus, the

heterogeneity of the population and the need to consider the unique etiology of every person with a brain

injury renders Class III evidence helpful in guiding the

direction of efficacy research even though its generalizability may be limited [22,49]. Given these challenges

with RCT’s, it is not uncommon for single subject design to be employed more frequently in rehabilitation

research. Further, while the number of well designed

controlled studies is increasing in ABI rehabilitation,

there is limited high level evidence currently available

to support various interventions [14,43].

362

C. Wiseman-Hakes et al. / Perspectives on evidence based practice in ABI rehabilitation

Consequently, it is beginning to be recognized that

for management and practice decisions in which randomized trials are not available, clinicians and guideline developers must still rely on Level II and Level III

evidence, including observational studies. Kunz [29]

reported that “indeed, for a great many questions of

clinical importance, observational studies constitute the

best available evidence” (p. 1).

An increased focus on individualized treatment protocols in ABI rehabilitation precludes the use of generalized group treatment programs. For example, a

number of specialists in brain injury rehabilitation are

advocates of the “Patient Specific Hypothesis Testing”

(PHST) approach to treatment, with its goal of “identifying the most effective intervention for a specific patient under specific life circumstances and in relation

to specific desired (i.e. individualized and contextually

based) outcomes” [64,65,49]. According to Ylvisaker et al. [64], PSHT also relies on the involvement of

relevant parties including the individual, their professionals, family members, colleagues, and significant

others. In addition to creating the intervention, PSHT

also serves to educate the relevant parties about the

impairment and intervention, provides strategies and

environmental modifications specific to the individual, and most importantly, involves the person with the

impairment (disability) in meaningful and systematic

problem solving and decision making, which are critical components of executive function [64]. Similarly,

the ‘Participate to Learn’ models of intervention focus

on roles as goals, learning by experience in real-life

contexts, and the use of personal and environmental

support to enable participation [5]. These approaches

to intervention are incompatible with RCT models in

which all subjects receive the same intervention protocol once they have met inclusion criteria. This leaves

the research community with a compelling question; Is

it possible to develop/utilize an RCT research methodology which allows for some individualization within

the standard treatment protocol? Not only would this

support a more valid implementation of a true clientcentered AND EBP, but it would help to address many

of the ethical criticisms applied to a more narrow view

of EBP. Thus, we advocate for a broader more pluralistic view of EBP [31] where the term “evidence” is synonymous with “reason”, and offer the following points

for consideration [67]:

1. Evidence is a scientific approach to measurement

of the effectiveness of intervention. Evidence

accounts for all that is rational and measurable in

the therapeutic process.

2. But, evidence in the narrow view (i.e. RCT’s)

is insufficient to capture the broader, yet equally

valid aspects of the therapeutic process including: the clinical relationship, context, change in

circumstances or therapeutic factors, and extraneous, non-rehabilitation factors.

3. A broader, more pluralistic view is required.

Specifically, a pluralistic approach is one that

considers the whole person, their daily life contexts, and supports, and is reflected within evidence generation, evidence search, and knowledge translation [4,26,31,35,51,52]. When this

pluralistic approach is applied to ABI/TBI rehabilitation and rehabilitation research, it is one

which advocates for a broader, more inclusive

definition of individualized treatment and thus a

broader scope of research methodology.

4. No amount of evidence can override the need for

clinical judgment [20].

Mykhalovsky and Weir [38] identified the concern that

(a more narrow view of) EBP does not take sufficient

account of patient values, and they stated further that

the inherent design of RCT’s makes their outcomes difficult to generalize over a diverse and heterogeneous

patient population (such as those with ABI). This is

in keeping with the view espoused by Guyatt [24], in

the last installment of the Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature whereby clinicians must rely on their

own judgment and expertise to define features that affect the generalizability of the results to the individual patient, recognizing the importance of context, and

patient values. Qualitative research can also play an

important role here in illustrating the individual differences and narratives during the rehabilitation process.

Thus, the clinician must judge the extent to which differences in the treatment (including skill and personality of the therapist), the availability of ongoing monitoring to ensure generalizability, or patient characteristics such as age, patterns of neurocognitive impairment, or concomitant treatment may affect estimates of

benefit and risk that come from the published literature.

Clinicians must further consider if the available studies

have measured all important outcomes, if patients were

followed up with for a sufficient length of time, and

if experimental treatment was compared with the most

compelling alternatives [24,37,64,65]. In addition to

their clinicians, most survivors themselves would agree

that nothing can substitute for the combination of clinical expertise, advocacy, empowerment, involvement

in the goal setting and decision making process, and a

C. Wiseman-Hakes et al. / Perspectives on evidence based practice in ABI rehabilitation

sound clinical relationship in determining and meeting

the specific considerations relevant to that person.

Thus, according to Guyatt et al. [24], “knowing the

tools of EBM/EBP is necessary, but in of itself, not sufficient for delivering the highest-quality patient/client

care. In addition to clinical expertise, the clinician requires compassion, sensitive listening skills, and broad

perspectives from the humanities and social sciences.

These attributes facilitate an understanding of the individuals’ illness (disability) within the unique context

of their experience, personality, and culture” (p. 1293).

This view would seem to be consistent with a broad

interpretation of EBP, wherein the term “evidence” is

synonymous with reason.

9. Key questions to consider when evaluating the

literature (and syntheses of the literature)

Below is a set of Key Questions to consider when

generating and applying evidence. These questions encourage a perspective that is broader than “will certain interventions work?” and include considerations

of why they work, in what treatment context, for which

patients, at what stage of their recovery, etc. [22].

Key Questions:

1. Are specific patient characteristics reported and

are those patient characteristics similar to my clinical

population?

2. Are subject groups equated by injury severity

alone or also by neuro-cognitive, communication and

behavioural characteristics?

3. Are treatments individualized or is the same standard protocol used for a group of patients?

4. Are the outcomes measured at the level of impairment/disability, activity limitations or participation?

There was an initial tendency in treatment research

to measure improvements solely on standardized tests

or clinical tasks [5,61]. However, The World Health

Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [60] provides an expanded

framework of analysis of impairment/disability from

the perspective of body structure and function, activity limitations, and participation restrictions within the

person’s unique environment, as well as consideration

of personal factors such as the individual’s motivation,

and factors such as family and school supports. This

expanded framework has directed clinicians working in

363

ABI rehabilitation towards increased options for outcome measurement [30]. Further, it is now recognized

that the effects of communication, cognitive, and behavioural interventions also need to be measured in real

world functional situations [9,18,22,28,30,52,58,61].

This generates yet another series of questions specific

to treatment outcomes: 1. Are the treatment outcomes

measured at the level of impairment, activity limitations

or participation? 2. Are the outcome instruments reflective of communication/behavioural/cognitive functioning or are they generic? 3. Are treatment effects

maintained over time?

5. What are the types of interventions used in the

study?

There are a number of considerations with regards

to the type of intervention. Initial comparisons of

treatment modalities in ABI efficacy research were

restricted to contrasts of restoration and compensation approaches [1,9,69]. Yet treatment modalities

have broadened considerably in the past 15 years with

the addition of approaches such as participation [5],

self coaching [62], apprenticeship models [67], communication partner training [51], and environmental approaches and curriculum based approaches in

schools [2]. Optimal use of a treatment modality depends on individual circumstances and needs [9,24].

Carney and colleagues [6] advise that improved efficacy research requires the use of standardized treatment

protocols even when individualized dynamic treatment

is being employed. One method of achieving standardization within individualized approaches is the use

of Goal Attainment Scaling [33], which can allow the

clinician to quantify improvements for individual goals,

consistent with a philosophy of client-centred practice.

6. Are the treatment methods contextualized for the

individual or decontextualized?

Another important consideration in analyzing the

type of intervention is to consider whether treatment

methods are a) contextualized, that is, for example,

based on the cognitive-communication, behavioural

and ADL (activities of daily living) demands of the individual’s life, or b) decontextualized, that is, structured,

often clinic based, tasks that may have little resemblance to the demands and complexities of daily life.

Ylvisaker [54] describes traditional cognitive intervention approaches as “cognitive exercises to restore cognitive processes or skills possibly combined with cognitive exercises to acquire compensatory cognitive behaviours with potentially general application” wherein the generalization sequence involves initial mastery

of skills in acquisition tasks followed by generaliza-

364

C. Wiseman-Hakes et al. / Perspectives on evidence based practice in ABI rehabilitation

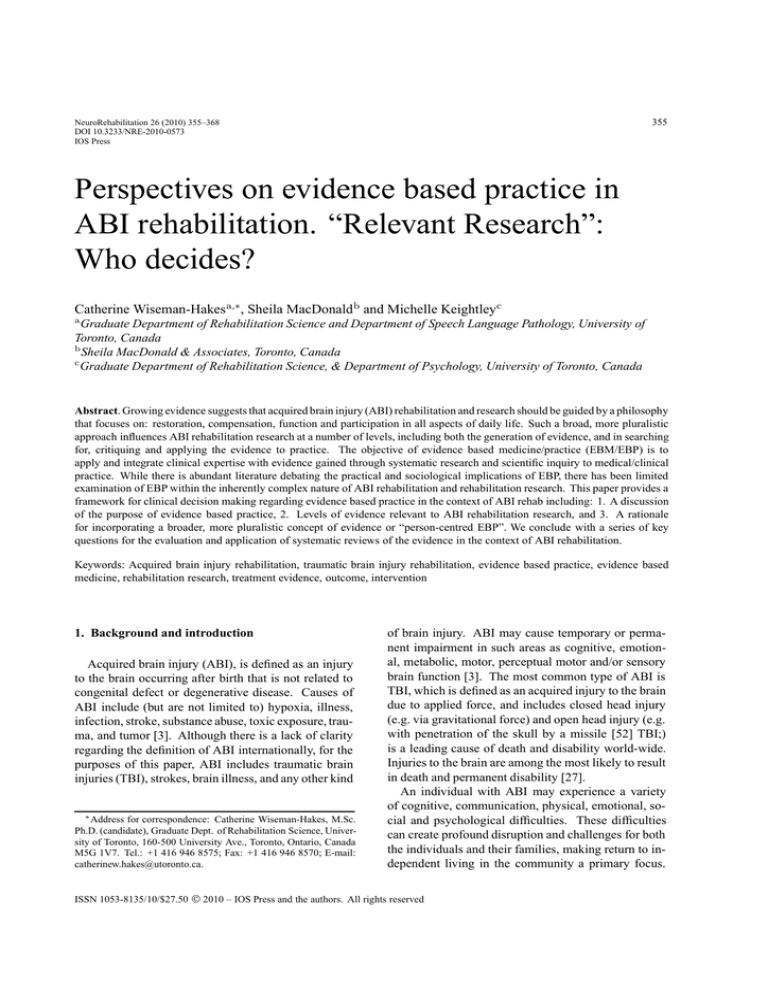

Table 2

A Comparison of traditional ABI evidence reviews and broader ‘pluralistic’ ABI evidence reviews

Traditional ABI intervention evidence based reviews

– Treatment variables controlled are those within sessions only

Pluralistic, contextual, broader evidence based reviews

– Contextual factors such as client communication interests,

demands of environment and communication partners are

considered

– Same treatment protocol for all

– Individualized treatment protocols

– Dependent variables or outcome measures tend to

be clinic based and then transfer and maintenance

are measured

– Outcome measures are functional, activity and participation

based – Use of WHO

– Real world performance and communication partner performance are measured

– RCT’s = Gold Standard

– SSD’s – (unique from case studies) are viewed as the best

means of analyzing treatment effects or RCT’s that allow for

individualized treatment protocol development

– Systematic Reviews = Consider RCT’s to be the

highest form of evidence

– Systematic Reviews include SSD’s

– SSD’s include effect sizes

– Meta analyses analyze treatment effects

RCT, Randomized Control Trial; SSD, Single-Subject Design.

tion tasks to promote transfer of skills to other situations or environments. According to Ylvisaker [62],

context sensitive approaches have as their primary goal

“to help individuals achieve their real-world objectives

and participation in their chosen real-world activities”.

In the contextualized treatment model, generalization

is promoted from the outset in a flexible combination of “task specific training, intervention for strategic thinking and compensatory behaviour in functional contexts and environmental modifications including

changes in the support behaviours of others”. Ylvisaker and Feeney [57,16] reviewed previously reported

challenges with transfer and generalization of skills,

and noted that in many fields there has been a shift

from decontextualized learning to context-sensitive intervention with supporting efficacy studies. In addition

to issues of transfer maintenance, the contextualized

approaches may be more motivating and engaging for

client participation [49]. Issues relating to motivation,

perceived relevance, self-awareness, and emotional engagement in rehabilitation must be underscored, particularly regarding interventions directed toward improving communication, in keeping with a participation model [4,54,56,57]. Contextualized approaches to

treatment have been found to be more effective than

standard clinic based interventions with a variety of

populations such as aphasia [22], developmental delay,

and attention deficit disorder [57].

7. Finally, an interesting and important consideration when evaluating individual studies and systematic reviews is what we call the evolution factor [28].

Efficacy studies have evolved over time in terms of

the specificity of patient selection criteria, assessment

methods, treatment group assignment, treatment methods, measurement of outcomes, and consideration of

transfer and maintenance. Clinicians and policy makers reviewing the evidence must place it (the evidence)

within its historical context in order to recognize where

a study occurred in the evolution of ABI interventions.

For example, earlier studies might have borrowed from

the stroke literature, and used aphasia tests to determine

severity of communication impairments, whereas later studies have focused more appropriately on aspects

of participation and social communication. The evolution factor requires that discerning clinicians evaluate the strength and applicability of the evidence, not

simply count the number of available studies. Overall,

in light of the evolution factor, the complexity of assessment and treatment, following ABI, and the multiple factors to be considered, clinicians will glean the

best guidance from systematic reviews that are recent,

and that are conducted by experts in the field under review, who know the theoretical framework, appropriate

definitions, assessment measures, treatment modalities,

and outcome measures.

Finally, there are numerous issues in evidence based

practice that are beyond the scope of this paper and

C. Wiseman-Hakes et al. / Perspectives on evidence based practice in ABI rehabilitation

365

Table 3

Critical appraisal of evidence: A brief guide for clinicians

Factors for consideration

– Inclusion exclusion criteria provided

– Representative of the population

Additional questions for clinicians

Do the participants match the patients/clients in my

practice?

– Population samples described according to demographics, length of time post injury, severity of injury & impairment,

– Sample size

– Attrition (who dropped out and why?)

Are those who dropped out the more vulnerable ‘in

need’, harder to treat group?

– Were efforts made to create contrasting treatment

conditions, and to equate samples and decrease

bias (i.e. randomization, blind raters, monitoring of

treatment provision, analysis of attrition)

Are these individual or group interventions relevant to

the individual I’m treating?

– Outcomes; were they standardized, do they measure

at the level of impairment, activity or participation

What outcome is my patient/client aiming for

– Were the findings statistically significant?

Does this equate with functionally and or clinically

significant for my patient/client?

Do I have the means to carry out this treatment in my

practice

– Is the description of the intervention sufficient to

replicate

– Was there follow-up to ensure maintenance and generalization of gains

Will the gains be maintained?

– Are there SSD data available for the intervention of

choice?

If so, did the study use multiple baselines across subjects and behaviours, as well as randomization of the

order of active treatment phases?

clinicians will find the following references helpful [16,

28]. A brief guide to critically appraising the evidence

can provide clinicians with important issues and related

questions, when applying the evidence to their own

clinical practice.

10. Conclusions

This paper advocates for a broader, more pluralistic

approach [35] to the generation, synthesis and application of evidence to support individualized, contextually based rehabilitation with participation and quality

of life as desired rehabilitation outcomes. There are

many issues to consider when evaluating and applying the evidence in ABI rehabilitation. There can be

differences in the scope and quality of systematic reviews from the perspective of: 1. The generation of

evidence, 2. The synthesis of evidence, and 3. The

application of evidence, given the unique complexities

and the contexts of individual client care. The goal of

generation of evidence for application to clinical practice is a noble one. However, there are difficulties in

how we marry the often divergent needs, backgrounds

and objectives of the authors of systematic reviews,

and the divergent needs of strict standardized scientific

methodology with needs of client-centred care and best

practice. The reality is that evidence based practice

may not always be synonymous with best practice (i.e.

client centred care), when a rigid or narrow definition

of evidence is employed. This also applies when the

qualifications, objectives, and theoretical framework of

the authors of research synthesis papers, in addition to

their search methodology, are analyzed and critiqued.

The ‘key questions’ listed address both ‘intervention research’ itself and act as a framework to evaluate

evidence that addresses not so much whether certain

interventions work, but why they work, in what treatment context, for which patients, and at what stage of

their recovery. By including such key questions in the

evaluation of research evidence, clinicians in the field

of ABI rehabilitation will be empowered with an additional resource to provide best practice (if not a traditionally defined evidence-based practice) at the point of

care, which has the potential to translate into improved

quality of life for clients during recovery from ABI.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express sincere gratitude to Dr.

366

C. Wiseman-Hakes et al. / Perspectives on evidence based practice in ABI rehabilitation

Mark Ylvisaker, Dr. Pia Kontos and Dr. Lyn Turkstra

for their editorial expertise in reviewing this paper at

various stages of its evolution. We dedicate this paper to

the memory of Dr. Mark Ylvisaker, colleague, mentor

and friend.

Ms. Wiseman-Hakes gratefully acknowledges the

support of the Canadian Institutes for Health Research

through a Fellowship in Clinical Research, and the

Toronto Rehabilitation Institute who receives funding

under the Provincial Rehabilitation Research Program

from the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care in Ontario, Canada. The views expressed do not necessarily

reflect those of the Ministry.

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

References

[1]

Y. Ben-Yishay and L. Diller, Cognitive remediation in traumatic brain injury: update and issues, Archives of Physical

Medicine & Rehabilitation 74 (1993), 204.

[2] J. Blosser and R. DePompei, Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: Proactive Intervention, in: Neurogenic Communication

Disorders Series, Singular Publishing, CA, 1994.

[3] Brain Injury Network: Definitions of ABI and TBI. Available:

http://www.braininjurynetwork.org/thesurvivorsviewpoint/

definitionofabiandtbi.html. (Accessed October 2009).

[4] A. Broom, J. Adams and P. Tovey, Evidence – based healthcare

in practice: A study of clinician resistance, professional deskilling and inter-specialty differentiation in oncology, Social

Science and Medicine 68 (2009), 192–200.

[5] P.M. Carlson, M.L. Boudreau, J. Davis, J. Johnston, C. Lemsky, M.A. McColl, P. Minnes and C. Smith, ‘Participation to

learn’; A Promising practice for community ABI rehabilitation, Brain Injury 20 (2006), 1111–1117.

[6] R.M. Carney, H. Chesnut, N.C. Maynard, P. Mann, M. Patterson and M. Helfand, Effect of cognitive rehabilitation on

outcomes for persons with traumatic brain injury: A systematic review, Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 14 (1999),

277–307.

[7] K. Cicerone, C. Dahlberg, J. Malec, D. Langenbahn, T. Felicetti, S. Kneipps, W. Elimo, K. Kalmar, J. Giacino, J.P.

Harley, L. Laatsch, P. Morse and J. Catanese, Evidence-based

cognitive rehabilitation: Updated review of the literature from

1998 through 2002, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 86 (2005), 1681–1692.

[8] R.M. Chestnut, N. Carney, H Maynard, N. Mann, Clay, P. Patterson, Patricia and M. Helfand, Summary Report: Evidence

for the Effectiveness of Rehabilitation for Persons with Traumatic Brain Injury, Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 14

(1999), 176.

[9] C. Coelho, F. Deruyter and M. Stein, Treatment efficacy:

cognitive-communicative disorders resulting from traumatic

brain injury in adults, Journal of Speech and Hearing Research

39 (1996), S5–S17.

[10] C. Coelho, M. Ylvisaker and L. Turkstra, Nonstandardized

assessment approaches for individuals with traumatic brain

injury, Seminars in Speech and Language 26 (2005), 223–241.

[11] H.M. Cooper, Organizing knowledge synthesis: A taxonomy

of literature reviews, Knowledge in Society 1 (1988), 104–126.

[19]

[20]

[21]

[22]

[23]

[24]

[25]

[26]

[27]

[28]

[29]

H.M. Cooper and L.V. Hedges, eds, The Handbook of Research

Synthesis, Russell Sage Foundation. NY, 1994.

J. Creswell, Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions, Sage, CA, 1998.

N. Cullen, J. Chundamala, M. Bayley, J. Jutai and E. Group,

The efficacy of acquired brain injury rehabilitation, Brain injury 21 (2007), 113–132.

M.P. Dijkers, Quality of life after traumatic brain injury: a review of research approaches and findings, Archives of Physical

Medicine and Rehabilitation 85(Suppl 2) (2004), 21–35.

C. Dollaghan, The Handbook for Evidence Based practice in

Communication Disorders, Paul Brookes Publishing Co., MA,

2007.

J.M. Douglas, C.A. Bracy and P. Snow, Exploring the factor structure of the Latrobe communication questionnaire; Insights into the nature of communication deficits following TBI,

Aphasiology 21 (2007), 1181–1194.

T.L. Eadie, K.M. Yorkston, E.R. Klasner, B.J. Dudgeon, J.C.

Deitz, C.R. Baylor, R.M. Miller and D. Amtmann, Measuring

Communicative Participation: A Review of Self-Report Instruments in Speech-Language Pathology, American Journal

of Speech-Language Pathology 15 (2006), 307–320.

T. Feeney and M. Ylvisaker, Context sensitive cognitivebehavioural supports for young children with TBI: (a second

replication study), Journal of Positive Behavioural Interventions 10 (2008), 115–128.

A. Furlan, G. Tomlinson, A. Jadad and C. Bombardier,

Methodological quality and homogeneity influenced agreement between randomized trials and nonrandomized studies

of the same intervention for back pain, Journal of Clinical

Epidemiology 61 (2008), 209–231.

W.D. Garvey and B.C. Griffith, Scientific communication: Its

role in the conduct of research and the creation of knowledge,

American Psychologist 26 (1971), 349–361.

L.A. Golper, R. Wertz, C. Frattali, K. Yorkston, P. Myers, R.

Katz, P. Beeson, M.R. Kennedy, K. Bayles and J. Wambaugh,

Evidence based practice guidelines for the management of

communication disorders in neurologically impaired individuals: Project introduction, Academy of Neurological Communication Disorders ANCDS Position Paper; August 2001

Available: http://www.ancds.org 1–12. Accessed March 15,

2009.

M.A. Gupta, Critical appraisal of evidence based medicine:

some ethical considerations, Journal of Evaluation in Clinical

Practice 9 (2003), 111–121.

G.H. Guyatt, R.B. Haynes, R.Z. Jaeschke et al., Users guide to

the medical literature, XXV: Evidence-based medicine: Principles for applying the user’s guides to patient care, Journal of

the American Medical Association 284 (2000b), 1290–1296.

J. Hinckley and T. Carr, Differential contributions of cognitive

abilities to success in skill-based versus context-based aphasia

treatment, Brain and Language 79 (2001), 3–6.

R.H. Horner et al., The Use of Single-Subject Research to

Identify Evidence-Based Practice in Special Education, Exceptional Children 71 (2005), 165–179.

International Brain Injury Association Available: http://www.

internationalbrain.org/?q=Brain-Injury-Facts. Accessed October 25, 2009.

M.R.T. Kennedy and L. Tursktra, Group intervention studies in

the cognitive rehabilitation of individuals with traumatic brain

injury: Challenges faced by researchers, Neuropsychology

Review 16 (2006), 151–159.

R. Kuntz, Randomized trials and observational studies: still

mostly similar results, still crucial differences, Journal of Clin-

C. Wiseman-Hakes et al. / Perspectives on evidence based practice in ABI rehabilitation

[30]

[31]

[32]

[33]

[34]

[35]

[36]

[37]

[38]

[39]

[40]

[41]

[42]

[43]

[44]

[45]

[46]

[47]

[48]

[49]

ical Epidemiology 61 (2008), 207–208.

B. Larkins, The application of the ICF in cognitivecommunication disorders following traumatic brain injury,

Seminars in Speech and Language 28 (2007), 334–342.

J. Lomas, T. Culyer, C. McCutcheon and L. McCauley, Law,

Conceptualizing and combining evidence for health system

guidance, Canadian Health Services Research Foundation

(CHSRF) Available from: www.chsrf.ca (2005) 1–43. Accessed May 9, 2009.

S. MacDonald and C. Wiseman-Hakes, Knowledge translation in ABI rehabilitation: A framework for consolidating and

applying the evidence for cognitive-communication interventions, Brain Injury 24(3) (2010), 486–508.

J.F. Malec, Goal attainment scales in rehabilitation, Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 9 (1999), 253–275.

M. McColl, P. Carlson, J. Johnston, P. Minnes, K. Shue and D.

Davies, The definition of community integration: Perspectives

of people with brain injuries, Brain Injury 12 (1998), 15–30.

B. McCormack, Evidence-based practice and the potential for

transformation, Journal of Research in Nursing 11 (2006),

89–94.

C.J. McReynolds, L.C. Koch and P.D. Rumrill, Qualitiative

research strategies in rehabilitation, Work 16 (2001), 57–65.

E. Montgomery and L. Turkstra, Evidence-based medicine:

Let’s be reasonable, Journal of Medical Speech-Language

Pathology 11 (2003), ix–xii.

E. Mykhalovsky and L. Weir, The problem of evidence based

medicine: Directions for social science, Social Science and

Medicine 59 (2004), 1059–1069.

M. Nochi, Struggling with the labeled self; People with traumatic brain injuries in social settings, Qualitative Health Research 8 (1998), 665–681.

S. Odom and P.S. Strain, Evidence-based practice in early

intervention/early childhood special education: Single subject

design research, Journal of Early Intervnetion 26 (2002), 151–

160.

M. Perdices, R. Schultz, R. Tate, S. McDonald, L. Togher, S.

Savage, K. Winders and K. Smith, The evidence base of neuropsychological rehabilitation in acquired brain impairment

(ABI): How good is the research?, Brain Impairment 7 (2006),

119–132.

L.G. Portney and M.P. Watkins, Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice, (2nd Edition), Prentice –

Hall, NJ, 2000.

L. Rees, S. Marshall, C. Hartridge, D. Mackie, M. Weiser and

E. Group, Cognitive interventions post acquired brain injury,

Brain injury 21 (2007), 161–200.

M. Rosenthal, B. Christensen and T. Rossreferences, Depression following traumatic brain injury, Archives of Physical

Medicine and Rehabilitation 79 (1998), 90–103.

D.L. Sackett, S.E. Strauss and W.S. Richardson, Evidence

Based Medicine, How to Practice and Teach, Churchill Livingston, Edinburgh, 2002.

D.L. Sackett, W.M. Rosenberg, J.A. Gray, R.B. Haynes and

W.S. Richardson, Evidence based medicine: What it is and

what it isn’t, British Medical Journal 312 (1996), 71–72.

D.A. Schön, The Reflective Practitioner. How Professionals

Think in Action, Aldershot, Avebury, 1991.

M.M. Sohlberg and M. Kennedy, Evidence based practice:

reminders and updates for clinicians who treat cognitivecommunication disorders after brain injury, Brain Injury Professional 6 (2009), 10–15.

M. Sohlberg, M.R.T. Kennedy, J. Avery, C. Coelho, L. Turkstra, M. Ylvisaker and K. Yorkston, Evidence based practice

[50]

[51]

[52]

[53]

[54]

[55]

[56]

[57]

[58]

[59]

[60]

[61]

[62]

[63]

[64]

[65]

367

for the use of external aids as a memory rehabilitation technique, Journal of Medical Speech Pathology 15 (2007), xv–li.

D. Steadman-Pare, A. Colantonio, G. Ratcliff, S. Chase and L.

Vernich, Factors associated with perceived quality of life many

years after traumatic brain injury, Journal of Head Trauma

Rehabilitation 16 (2001), 330–342.

L. Togher, S. McDonald, C. Code and S. Grant, Training the

communication partners of people with traumatic brain injury,

Aphasiology 18 (2004), 313–355.

L. Turkstra, M. Ylvisaker, C. Coelho, M. Kennedy, M.

Sohlberg and J. Avery, Practice guidelines for standardized

assessment for persons with traumatic brain injury, Journal of

Medical Speech-Language Pathology 13 (2005), ix–xxxviii.

R.E. Upsher, Seven characteristics of medical evidence, Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 6 (2000), 93–97.

R.E. Upsher, If not evidence, then what? Or does medicine

really need a base? Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice

8 (2002), 113–119.

R.E. Upsher and C.S. Tracey, Legitimacy, authority, and hierarchy: Critical challenges for evidence based medicine, in:

Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, Oxford University

Press, NY, 2004.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force http://www.ahrq.gov/

CLINIC/uspstfix.htm Agency for Healthcare Research and

Quality: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services:

Accessed January 18, 2009.

R.D. Vanderploeg, R. Collins, B. Sigford, E. Date, K. Schwah

and D. Warden, Practrical and theorietical considerations in

designing rehabilitation trials. The DVBIC Cognitive-didactic

versus functional-experimental treatment study experience,

Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 21 (2006), 179–193.

E. Van Leer and L. Turkstra, The Effect of elicitation task on

discourse coherence and cohesion in adolescents with brain

injury, Journal of Communication Disorders 32 (1999), 327–

349.

C.R. Webb, M. Wrigley, W. Yoels and P.R. Fine, Explaining

quality of life for persons with traumatic brain injuries 2 years

after injury, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

76 (1995), 1113–1119.

World health Organization (WHO) International Classification

of Functioning, Disability and Health: Geneva (2002). Available online at http://www3.who.int/icf/onlinebrowser/icf.cfm,

accessed April 17, 2009.

L. Worrall R. McCooey, B. Davidson, B. Larkins and L. Hickson, The validity of functional assessments of communication

and the Activity/Participation components of the ICIDH-2:

do they reflect what really happens in real-life?, Journal of

Communication Disorders 35 (2002), 107–137.

M. Ylvisaker, Self-Coaching: A context-sensitive, person centred approach to social communication after traumatic brain

injury, Brain Impairment 7 (2006), 246–258.

M. Ylvisaker, Children with cognitive, behavioural, communication and academic disabilities, in: Rehabilitation for Traumatic Brain Injury, H.W. Sander, M. Struchen and K. Hart,

eds, Oxford University Press, NY, 2005, pp. 205–234.

M. Ylvisaker, C. Coelho, M. Kennedy, M. Sohlberg, L. Turkstra, J. Avery and K. Yorkston, Reflections on evidence-based

practice and rational clinical decision making, Journal of Medical Speech-language Pathology 10 (2002), xxv–xxxiii.

M. Ylvisaker, R. Hanks and D. Johnson-Greene, Perspectives

on rehabilitation of individuals with cognitive impairment after brain injury; Rationale for reconsideration of theoretical

paradigms, Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 17 (2002),

191–209.

368

[66]

C. Wiseman-Hakes et al. / Perspectives on evidence based practice in ABI rehabilitation

M. Ylvisaker and T. Feeney, Construction of identity after

traumatic brain injury, Brain Impairment 1 (2000), 12–28.

[67] M. Ylvisaker and T. Feeney, Executive functions after traumatic brain injury; Supported cognition and self advocacy,

Seminars in Speech and Language 17 (1999), 217–235.

[68] M. Ylvisaker, L. Turkstra, C. Coelho, K. Yorkston, M.

Kennedy and M. Sohlberg, Behavioural interventions for children and adults with behaviour disorders after TBI: A systematic review of the evidence, Brain Injury 21 (2007), 769–805.

[69] M. Ylvisaker, B. Urbancyk and T. Feeney, Social skills following traumatic brain injury, Seminars in Speech and Language

13 (1992), 308–322.