Service Delivery Models, Systematic Review

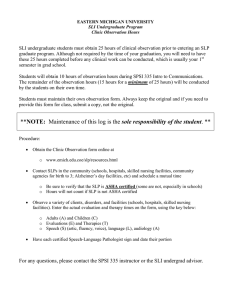

advertisement