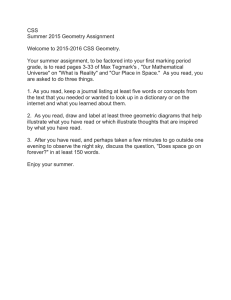

Community Systems Strengthening Framework

advertisement