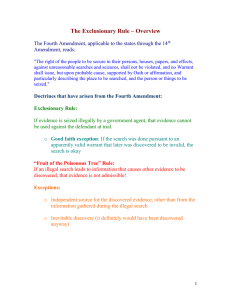

the framers` fourth amendment exclusionary rule

advertisement