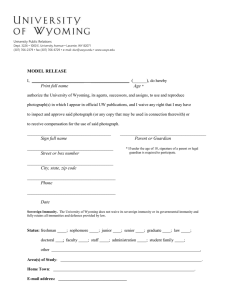

State Sovereign Immunity and Privatization

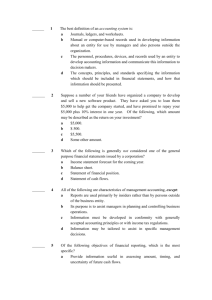

advertisement