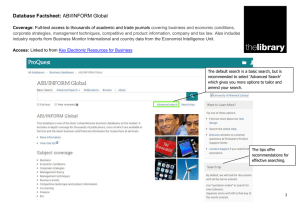

global food security index 2013

advertisement