Impact of corporate strengths/weaknesses on project management

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

International Journal of Project Management 27 (2009) 629–637 www.elsevier.com/locate/ijproman

Impact of corporate strengths/weaknesses on project management competencies

Zeynep Isik

a

, David Arditi

a,*

, Irem Dikmen

b

, M. Talat Birgonul

b a

Dept. of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering, Illinois Institute of Technology, 3201 South Dearborn Street, Chicago, IL 60616, United States b

Dept. of Civil Engineering, Middle East Technical Univ., 06531 Ankara, Turkey

Received 22 June 2008; received in revised form 27 September 2008; accepted 2 October 2008

Abstract

The project is at the core of the construction business. Project management can be used as a tool to maximize the success of projects and ultimately the success of construction companies. It is therefore worthwhile to explore the factors that can enhance project management competencies. In this study, it was hypothesized that ‘‘project management competencies ” are influenced by ‘‘corporate strengths/ weaknesses ” . ‘‘Corporate strengths/weaknesses ” was defined as a second-ordered construct composed of three latent variables including the company’s resources and capabilities, its strategic decisions, and the strength of its relationships with other parties. The data obtained from a questionnaire survey administered to 73 contractors were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM). The results of the study verified the hypothesis suggested.

Ó 2008 Elsevier Ltd and IPMA. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Corporate strengths/weaknesses; Project management competencies; Company resources and capabilities; Strategic decisions; Strength of relationships

1. Introduction

The construction industry is a project oriented industry. Effective project management is key for the successful accomplishment of sophisticated projects

.

Jaselskis and Ashley

state that construction projects commonly experience uncertainty because of shortages in resources and the nature of the project. The factors that are conducive to successful project management are abundantly discussed in the literature. For example,

Munns and Bjeirmi

suggest that the factors of success in project management include commitment to complete the project, appointment of a skilled project manager, adequate definition of the project, correctly planning the activities in the project, adequate information flow, accommodation of frequent changes, rewarding the

*

Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 312 5675751; fax: +1 312 5673519.

E-mail addresses: zisik1@iit.edu

(Z. Isik), arditi@iit.edu

(D. Arditi), idikmen@metu.edu.tr

(I. Dikmen), birgonul@metu.edu.tr

(M.T. Birgonul).

0263-7863/$34.00

Ó 2008 Elsevier Ltd and IPMA. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.10.002

employees, and being open to innovations. The environment in which the project takes place was also taken into account by many researchers

. That the use of the appropriate management techniques contributes to successful project management is also stressed by many researchers e.g.,

. The literature appears to emphasize project-related factors at the expense of companyrelated factors such as a company’s resources and capabilities, its strategic decisions, and the strength of its relationships with other parties.

It should be kept in mind that a company is an organization that supports the many projects undertaken by the company, generally in different geographical locations and administered by quite autonomous project managers but relying heavily on the support of the head office. In that sense, every project is somewhat influenced by the policies and culture of the central company organization. The objective of the study reported in this paper is to explore the impact of corporate strengths/weaknesses on project management performance.

630

2. Corporate strengths/weaknesses

Construction companies should be cognizant of their strengths and weaknesses in order to overcome the challenges of increased competition. However, the intangible nature of corporate level characteristics makes it difficult to assign them as strengths/weaknesses

. Based on a literature review and the responses of experts in a pilot survey, the corporate strengths/weaknesses were defined in the study by three constructs including a company’s resources and capabilities, its strategic decisions, and the strength of its relationships with other parties. These variables are described below.

2.1. Resources and capabilities

Z. Isik et al. / International Journal of Project Management 27 (2009) 629–637

Corporate strengths/weaknesses are defined in the study to reflect three dimensions: the company’s resources and capabilities relative to finances, technical and human capital, research and development, receptiveness to innovation; its strategic decisions relative to differentiation, market/client/partner selection, investment, organizational and project management; and the strength of its relationships with other parties such as clients, unions, and the government. Project management competencies are defined by the factors set forth by different researchers e.g.,

Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBoK)

and the suggestions of construction professionals contacted in a pilot study. All relevant factors are described in detail in the next two sections. A questionnaire survey was administered to a number of construction companies to test the hypothesis that corporate strengths/weaknesses have a significant impact on project management competencies. The hypothesis was tested using structural equation modelling (SEM), a statistical tool described later in the paper.

In the language of traditional strategic analysis, a company’s resources and capabilities are the strengths that companies can use to conceive of and implement their strategies

[12,13] . A company’s resources and capabilities

may be defined as its tangible and intangible assets. They include the company’s financial resources, technical competencies, leadership characteristics, experience, and image in the industry, research and development capabilities, and innovation tendencies.

Financial resources indicate a company’s credibility and reputation among clients and suppliers as well as its strength in the market in terms of its capacity to carry out projects

[14] . Having strong financial resources may

enable a company to get into more risky situations which in turn have higher benefits. The financial strength of a company is indicated by profitability and turnover and generally by the ratio of the company’s liabilities to equities. The majority of construction projects are funded by the owner who pays the contractor periodically, who in turn pays the subcontractors, the suppliers and other parties of the project for services rendered. The success of this routine depends on the financial strength of the owner as well as of the contractor

Technical competency

.

refers to the physical assets of a company such as machinery and equipment and the extent of technical knowhow available that is necessary to undertake specific projects. According to Shenhar and Dvir’s

project management theory, fulfilling technological specifications is one of the major factors in the achievement of success in a project

[17,18] . According to Warszawski

[14] , a company’s technical competency can be assessed

by analyzing the company’s preferred construction methods, the experience of its technical staff, the productivity and speed of its construction activities and the quality of the company’s output.

Leadership involves developing and communicating mission, vision, and values to the members of an organization.

A successful leadership is expected to create an environment for empowerment, innovation, learning, and support

. Researchers have examined the links between leadership styles and performance

. Fiedler

has emphasized the effectiveness of a leader as a major determinant in success or failure of a group, organization, or even an entire country. It is argued that the negative effects of external factors in a project environment can be reduced by the training end equipping of leaders with different skills

. Organizations require leadership for any of their decisions or actions

Experience can be achieved only if the lessons learned from completed projects are kept in the organizational memory and used in future projects

learning is difficult for companies because of the fragmented and project-based structure of the industry. This difficulty can be altered by knowledge management activities and a continuous organizational learning culture

.

The image of the company provides an impression of the products, services, strategies, and prospects compared to its competitors

[28] . Contractors in the construction industry

have to portray an image that addresses the expectation and demand of the clients and users like in all other market oriented industries. A positive image may enable higher profitability by attracting better clients and investors and increasing the value of the product

Research and development capability has a positive impact on competitive advantage in response to the increased requirements of the globalized industry. The dynamic and rapid changing nature of the industry forces construction companies to develop and adopt new technologies in order to survive in a competitive environment.

Innovation capability constitutes the link between the company and the dynamic environment of the industry

[30] . The construction industry is not static and introverted

any more. Globalization and higher rates of competition between companies force construction companies to change. Innovation capability is an important factor in achieving cost leadership, focus, and differentiation, hence enhancing competitiveness as stated by Porter

.

Z. Isik et al. / International Journal of Project Management 27 (2009) 629–637

According to Arditi et al.

, innovations are rather incremental than radical in the construction industry. Also construction is a supplier dominated industry. Construction companies are dependent on other industries (e.g., construction material, manufacturers, equipment manufactures and others for technological innovations such as new construction processes and methods). Alternative corporate structures, financing methods etc. can also be considered as potential innovation areas in the construction industry

2.2. Strategic decisions

The literature on strategic decision making is spread over a wide range from an individual strategist’s perspective to strategic management techniques, to the implementation of these techniques in real situations

. The strategies selected for this study (see below) represent the characteristics of the construction industry as a projectbased organization.

Differentiation strategies refer to the differentiation of products or services that provides competitive advantage and allows a company to deal effectively with the threat of new entrants to the market

companies enter the industry every year because starting a new company does not require a large investment; consequently the construction industry becomes more competitive and forces existing companies to seek advantages over competitors by means of differentiation strategies that allow them to undertake projects that the new entrants cannot do.

Market, project, client, and partner selection strategies are related to characteristics of such as market conditions, the location and complexity of the project, the financial stability of the client, and potential partners that have capabilities that the company does not possess.

Project management strategies can be developed by referring to the mission of the company and the company’s business environment. The managerial functions of a project include activities such as planning, cost control, quality control, risk management, safety management, to name but a few. In order to achieve project goals, adequate strategies have to be set up relative to these functions.

Investment strategies occur along several dimensions such as capabilities of the company (resources), pricing

(financial decisions), product (construction project-related factors), and finally research and development

Organizational management strategies involve decisions pertaining to the company’s reporting structure, planning, controlling and coordinating systems, as well as the management of the informal relations among the different parties within the company

.

2.3. Strength of relationships with other parties

The strength of a company’s relationships with other parties constitutes a social dimension of project environment

. The strength of relationships with the parties involved in typical construction projects such as public or private clients, regulatory agencies, subcontractors, labor unions, material dealers, surety companies, and financial institutions constitute an important aspect of a company.

The strength of these relationships is related to the mutual satisfaction of the parties, i.e., the realization of the expectations of the parties. The primary relationships that are of more importance than others include relationships with construction owners (both public and private), labor unions, and regulatory agencies. But the subtle difference between favoritism and the strength of relations has to be distinguished while assessing this criterion.

Relationships with clients rely on the communication and negotiating skills of company executives. The difficulty of achieving strong relationships between clients and contractors has always been a matter of concern, but recently the importance of cooperation and trust between clients and contractors has been understood somewhat better

The awareness of the influence of good relationships on performance encouraged contractors to recognize clients’ basic expectations relative to cost, time and quality

On the other hand, good relationships are characterized by timely payments on the part of the owner, fewer claims on the part of the contractor, and the absence of legal disputes.

Relationships with labor unions relates to the human resources management of the company. Contractors should pay attention to formulating fair employment policies and to recognize labor rights. Labor unions have the right to strike in case the company engages in serious labor practices

[41] . Smooth labor relations minimize disputes

and strikes, and prevent potential delays.

Relationships with the government depends on the compromise of the government policies and the implementations of regulatory agencies with the companies in the construction industry. In general terms, bureaucratic obstacles set by regulatory agencies to maintain standards in companies’ day-to-day operations (e.g., codes, inspections, approvals, etc.), and companies’ difficulties in obtaining preferential financial support are some of the government-induced problems. On the other hand, tax incentives, and relaxation of customs duties to allow the import of some materials and to prevent shortages are encouraging government actions

.

3. Project management competencies

631

The project is at the core of the construction business and project management can be used as a tool to maximize the success of a project

[3] . The implementation process is

normally uniform across all projects even though each project is unique

. Nine project management knowledge areas were identified based on a review of the literature and a limited number of interviews with construction professionals during the pilot study of the research. The selection of these factors was based on their potential to impact the

632 success of a project through the implementation process.

Various project management success factors were identified in the literature such as communication, control mechanisms, feedback capabilities, troubleshooting, coordination, decision making, monitoring, project organization, planning and scheduling, and management experience

[44–46] . However, in this study, project management com-

petencies were investigated rather than the success factors.

Therefore the project management areas described briefly below were considered with their potential influence on project success.

Schedule management enables the project to complete on time by the use of a series of processes, including activity definition, sequencing, resource estimating, duration estimating, schedule development and schedule control

A project manager has to be familiar with the project environment and the conditions that may be the cause of potential delays.

Z. Isik et al. / International Journal of Project Management 27 (2009) 629–637

Cost management activities include planning, estimating, budgeting, and controlling the costs of the project

these activities ensure the lowest possible overall project cost consistent with the owner’s investment objectives.

Quality management refers to the activities that determine quality policies, objectives, and responsibilities. The processes of a quality management system include quality planning, quality assurance, and quality control

struction companies are incrementally implementing total quality management (TQM) for improving customer satisfaction, obtaining better quality products and higher market share. The main success of TQM depends on the commitment of top management and willingness to change the quality culture

Human resources management is an inevitable dimension of project management since it is people who deliver projects. People are the predominant resource in an organization and there is a positive association between human resources management practices and achievement of outstanding success

. Organizing and managing the project team are the main duties of human resources management.

Risk management processes include identification, analysis, responses, monitoring and control of risks. Considering the complex, dynamic and challenging nature of construction projects, risk in a construction project is unavoidable and affects productivity, performance, quality and budget significantly. However, risk can be transferred, accepted, minimized, or shared

[50] . Proper management of risk

has the potential to decrease the effects of unexpected events

Supply chain management is the network of different parties, processes and activities that produce products or services

.

The owner, consultants, contractor, subcontractors and suppliers constitute the supply chain in construction. Higher success can be achieved by increasing the quality of communication between different parties and team operation among different parties

of public sector construction initiatives in the UK, including the Latham Report

and the Egan Report

emphasized the benefits of improving supply chain management.

Claims management is of particular importance because the construction activity involves a large number of parties, an environment conducive to conflicts. Documentation, processing, monitoring and management of claims are a part of contract life cycle

[10] . Claims and disputes between

construction owners, contractors and other participants can be avoided by clearly stated contractual terms, early nonadversarial communication, and a good understanding of the causes of claims

Knowledge management is defined as a vehicle fuelled by the need for innovation and improved business performance and client satisfaction

[53,55,56] . The capability of

a company to cope with sophisticated projects is the result of a successful knowledge management

essential to keep information on best practices in order to learn lessons and not to duplicate the mistakes.

Health and safety management aims to reduce the number of accidents and accidents’ effects on project costs such as the cost of insurance, inspection and conformance to regulations

[57] . Potential solutions to health and safety

problems include providing safety booklets, safety equipment, and a safe environment; appointing a trained safety representative on site; training workers and supervisors; and using new technologies

.

4. Research methodology

A questionnaire consisting of questions about the latent variables and their constituent variables explained in the preceding sections was designed to analyze the influence of ‘‘corporate strengths/weaknesses ” on ‘‘project management competencies ” . The questions were designed to seek the perceptions of the respondents relative to company resources and capabilities, strategic decisions, the strength of the company’s relationships with other parties, and project management competencies in the company. An example question would read ‘‘How successful do you think your company is in schedule management?

” The respondent would rate the answer on a scale of 1–5, where 1 represents ‘‘not successful ” and 5 ‘‘very successful ” .

The questionnaire was administered via e-mail and faceto-face interviews to 185 construction companies established in Turkey. The target construction companies were all members of the Turkish Contractors Association

(TCA) and the Turkish Construction Employers Association (TCEA). The 185 companies received an e-mail describing the objective of the study, inquiring about their willingness to participate in the study and requesting a face-to-face interview with an executive of the company.

Forty seven questionnaires were completed, the majority of which were administered by face-to-face interviews.

The rate of response was 25%. However, considering the fact that there were other construction companies in the industry which were not members of TCA or TCEA but

showing similar characteristics with the member companies of these two associations in terms of size and type of work undertaken, a decision was made to expand the survey by including 26 additional similar companies selected individually through personal contacts. At the end of the extended survey, there were 26 more completed questionnaires, bringing the total number of respondents to 73. The variables associated with the survey questions were described in the preceding sections and are presented in

5. Data analysis

Z. Isik et al. / International Journal of Project Management 27 (2009) 629–637

The data collected from 73 respondents were analyzed using a software package called EQS 6.1, a structural equation modeling (SEM) tool. SEM is a statistical technique that combines a measurement model (confirmatory factor analysis) and a structural model (regression or path analysis) in a single statistical test

.

The first step in SEM is the validation of the measurement model through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

While conducting CFA, construct validity should be satisfied by using content validity and empirical validity tests.

Once the measurement model is validated, the structural relationships between latent variables are estimated

.

633

Content validity tests rate the extent to which a constituent variable belongs to its corresponding construct. Since content validity cannot be tested by using statistical tools, an in-depth literature survey is necessary to keep the researcher’s judgment on the right track

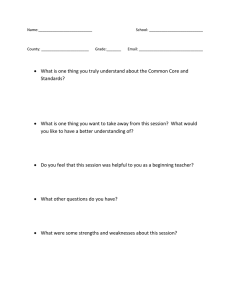

literature survey was conducted to specify the variables that define latent variables. The model was tested in a pilot study administered to industry professionals and academics. Based on the input of these subjects, the model was restructured, eliminating some of the variables and adding recommended ones. Content validity was thus achieved. In the proposed model, ‘‘corporate strengths/weaknesses ” is considered to be a three-dimensional and 2nd order construct composed of ‘‘company resources and capabilities ” ,

‘‘strategic decisions ” , and ‘‘strength of relationships with other parties ” ; its effect on ‘‘project management competencies ” is tested. In other words, the structure of the model involves a second order construct whereby a latent variable

(corporate strengths/weaknesses) is represented by three latent variables (company resources and capabilities, strategic decisions, strength of relationships with other parties)

( Fig. 1 ). The second order approach is recommended by

Hair et al.

as it maximizes the interpretability of both the measurement and the structural models. The heavy

Financial resources

Technical competency

Leadership

Experience

Company image

R&D capability

Innovation capability

0.63

0.71

0.75

0.54

0.51

0.70

0.75

COMPANY

RESOURCES

AND

CAPABILITIES

Differentiation strategies

Market selection strategies

Project selection strategies

Client selection strategies

Partner selection strategies

Project management strategies

Investment strategies

Org. management strategies

0.68

0.65

0.73

0.70

0.73

0.71

0.68

0.65

STRATEGIC

DECISIONS

0.94

0.93

0.91

CORPORATE

STRENGTHS/

WEAKNESSES

0.93

0.67

0.70

0.70

0.80

0.65

PROJECT

MANAGEMENT

COMPETENCIES

0.66

0.66

0.77

0.72

Schedule management

Cost management

Quality management

Human resources management

Risk management

Supply chain management

Claims management

Knowledge management

Health and safety management

Relations with clients

Relations with government

Relations with labor unions

0.61

0.59

0.79

STRENGTH

OF RELATION SHIPS

WITH OTHER

PARTIES

Fig. 1. Structural equation model.

634 arrow in

Z. Isik et al. / International Journal of Project Management 27 (2009) 629–637 defines the direction of the influence between two constructs, while light arrows define the dimensions of latent variables. Empirical validity tests follow content validity.

Scale reliability is the internal consistency of a latent variable and is measured most commonly with a coefficient called Cronbach’s alpha. The purpose of testing the reliability of a construct is to understand how each observed indicator represents its correspondent latent variable. A higher Cronbach’s alpha coefficient indicates higher reliability of the scale used to measure the latent variable

. According to the EQS analysis results, Cronbach’s alpha values were, 0.84 for ‘‘company resources and capabilities ” , 0.88 for ‘‘strategic decisions ” , 0.71 for ‘‘strength of relationships with other parties ” , 0.93 for ‘‘project management competencies ” , and 0.95 for the ‘‘overall model ” , all well beyond the threshold of 0.70 recommended by

Nunally

indicating that scale reliability has been achieved. The reliability of the ‘‘corporate strengths/weaknesses ” construct was also observed to be 0.93, which justifies the use of a three-dimensional construct with a twostep approach.

Unidimensionality refers to the degree to which constituent variables represent one underlying latent variable.

CFA was used to test for unidimensionality. Initially,

CFA was conducted independently for each construct.

Once each construct in the model was deemed unidimensional by itself, then unidimensionality was tested for all possible pairs as recommended by Garver and Mentzer

and Dunn et al.

.

Convergent validity is the extent to which the latent variable correlates to corresponding items designed to measure the same latent variable. If the factor loadings are statistically significant, then convergent validity exists.

shows the factor loadings marked next to light arrows corresponding to the five constructs of the model; note that all of the factor loadings are significant at a = 0.05.

Another way of assessing construct validity is the goodness-of-fit of the model. A number of fit indices are available, but Marsh et al.

propose that ideal fit indices should have: (1) relative independence of sample size; (2) accuracy and consistency to assess different models; and

(3) ease of interpretation aided by a well defined continuum or pre-set range. Many fit indices do not meet these criteria, because they are adversely affected by sample size

non-normed fit index (NNFI) considers a correlation for model complexity

. The comparative fit index (CFI) is interpreted in the same way as the NNFI and represents the relative improvement in fit of the hypothesized model over the null model. The root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) is an estimate of the discrepancy between the observed and estimated covariance matrices in the population

. The v

2 compares the observed covariance matrix to the one estimated on the assumption that the model being tested is true. But, when the sample size is small, it is difficult to obtain a v

2 that is not statistically significant; in such situations, the ratio of v

2 to degree of

Table 1

Reliability value and goodness of fit indices of the overall model.

Fit indices Recommended value

Overall model

Cronbach’s alpha

Non-normed fit index (NNFI)

Comparative fit index (CFI)

>0.7

0 (No fit)-1

(perfect fit)

0 (No fit)-1

(perfect fit)

<0.1

0.95

0.87

0.86

0.08

Root mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) v

2

/Degree of freedom <3 450/

315 = 1.43

freedom (dof) is to be examined. Based on the stated criteria and the suggestions made by Garver and Mentzer

(RMSEA) and (4) the ratio of v tencies and

”

6. Discussion of the findings

. The hypothesis set in the study that ‘‘corporate strength/weaknesses ” which is defined by ‘‘company resources and capabilities ”

2 ment model shows a good fit to the data.

with a path coefficient of 0.93.

were found to be highly satisfactory as shown in

, ‘‘strategic decisions

‘‘strength of relationships with other parties ”

”

Bentler and Yuan

, and Jackson

, (1) the nonnormed fit index (NNFI); (2) the comparative fit index

(CFI); (3) the root mean squared error of approximation to dof were selected in this study since they are less affected by sample size compared to other goodness-of-fit indices. Bentler

also recom-

The CFI and NNFI values of 0.87 and 0.86 also demonstrate a good fit of the model to the data. Moreover, the

RMSEA value was found to be satisfactory as it was below the recommended value of 0.10

. All in all, the measure-

In the second step of the analysis, SEM tests the hypothesized relationships between the validated constructs. The

According to the model, ‘‘corporate strength/weaknesses in the development of ‘‘project management competencies

” has a significant impact on ‘‘project management compe-

All criteria including Cronbach’s alpha values, factor loadings, path coefficients and goodness of fit indices which were used to measure the reliability and fit of the model

and is a key factor

”

, mends using robust methodology in EQS to handle nonnormality and to avoid the limitations of small sample size.

Robust analysis leads to corrected v 2 statistics and fit indices. In this study, robust analysis is performed and robust statistics are presented in

. According to the values presented in

, the v

2 to dof ratio was satisfactory as it was smaller than 3, the threshold suggested by Kline

.

relationship between the latent variables was hypothesized with a heavy arrow in

which represents the direction of the influence. The path coefficient marked on this heavy arrow is calculated for a 95% confidence level and can be interpreted similar to a regression coefficient that describe the linear relationship between two latent variables

.

is therefore verified by the findings. The influence of the determinants that take a project to success or failure has been investigated by several researchers e.g.,

, the majority of whom pointed out the importance of ‘‘project management competencies ” among other criteria.

Based on the findings, it can be stated that ‘‘corporate strengths/weaknesses ” plays an important role on the success of projects since it has a direct and significant influence on ‘‘project management competencies ” . The positive influence of company wide characteristics on project management competencies is also supported by other studies.

According to the strategic management literature, companywide characteristics are defined as the strengths of a company and the strengths of a company have the potential to be translated into an opportunity for the company as well

Z. Isik et al. / International Journal of Project Management 27 (2009) 629–637

‘‘Company resources and capabilities ” which is one of the determinants of ‘‘corporate strengths/weaknesses ” with a factor loading of 0.94 (

), depends on the size of the company and the competitive environment in which the company operates. In order to have a positive impact on project success, company resources and capabilities should be valuable, rare, inimitable, and should lack of substitutes

[12,74] . Based on their higher factor loadings in

can be stated that ‘‘leadership ” , ‘‘company image ” ,

‘‘research and development capability ” and ‘‘innovation capability ” are important resources and capabilities. While leadership is of importance in the execution of all project management activities, ‘‘company image ” , ‘‘research and development capability ” , and receptiveness to ‘‘innovation ” can be considered as sources of competitive advantage. Leadership in developing and using innovative management techniques is expected to affect at least some project management competencies.

‘‘Strategic decisions ” , with a factor loading of 0.93 is a major indicator of ‘‘corporate strengths/weaknesses ” , and in turn impacts project management competencies significantly. Emphasizing the importance of strategic decisions, Child

states that companies can achieve higher organizational success by adopting different competitive positioning alternatives based on strategic decisions. The strategic decisions construct in the study was represented by eight constituent variables, all closely related to competition. All have the power to manipulate the course of action in a project. Market/project/client/ partner selection strategies conducted along with differentiation, investment and organizational management strategies can constitute important corporate strengths (or weaknesses), which in turn can impact project management competencies. For example, differentiation strategies that add uniqueness and value to a company’s competitive arsenal

can have an impact on almost all project management competencies. Market, project, client, partner selection is likely to impact project management competencies such as knowledge management, risk management, claims management and cost management. The influence of investment strategies on cost management is obvious. Similarly, the effect of organizational management strategies on the human resources and knowledge management competencies of project management is well established.

‘‘Strength of relationships with other parties ” was also found to be loading significantly on ‘‘project management competencies ” . The positive influence of strong relationships with other parties was also discussed and confirmed in the literature e.g.,

[77–80] . The strength of the relation-

ships between the contractor and the client facilitates the operations and helps to achieve better performance.

According to Pinto and Mantel

and Dissanayaka and Kumaraswamy

, good relationships between a construction management firm and the client’s representatives expedite the operations and help to achieve success. Considering the sophisticated nature of the industry and the cultural values of the society, the relationship of a construction company were assessed not only with the client, but also with government agencies and labor unions. On this account, the communication and negotiation skills of company executives have to be stressed. The strength of a company’s relationships with other parties is expected to impact project management competencies such as quality management, claims management, human resources management.

7. Conclusion

635

The impact of corporate strength/weaknesses on project management competencies was investigated in this study.

According to the model presented in

strengths/weaknesses are defined by the latent variables

‘‘company resources and capabilities ” , ‘‘strategic decisions ” and ‘‘strength of relationships with other parties ” .

It was hypothesized that ‘‘corporate strengths/weaknesses ” , so defined, impacts ‘‘project management competencies ” . In order to test this hypothesis, a questionnaire survey was administered to 73 Turkish construction companies. A two-step SEM model was set up to measure the five latent variables (project management competencies, company resources and capabilities, strategic decisions, strength of relationships with other parties, and corporate strengths/weaknesses) through their constituent variables and to see if the hypothesized relationship holds (

According to the findings of the SEM analysis (

and

), Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of all the latent variables were well over the 0.70 min set by Nunally

which indicated that the internal reliability of the individual constructs was quite high. The internal reliability of the overall model was also found to be 0.95 which is an excellent result. CFA showed that all factor loadings presented in

were significant at a = 0.05. Limitations due to the small sample size are overcome by using robust methodology and the goodness of fit indices presented in

Table 1 . The indices consistently indicated a good fit, con-

sidering the recommended values. As a result, it can be concluded that the hypothesis set at the beginning of the

636 study was verified by the statistically significant ( a = 0.05) and very strong path coefficient (0.93) shown in

.

Beyond the success criteria commonly mentioned in previous research on project management e.g.,

, the considerable influence of corporate strengths/weaknesses was confirmed by the finding of this study. This finding adds a different perspective to success criteria in project management, and is particularly important since construction is largely project-based. Based on the findings of the study, it can be stated that companies should adjust their resources and capabilities, their longterm strategies and their relationships with other parties to better serve the needs of the individual projects. Indeed, in the dynamic environment of the construction industry, companies have to behave farsighted in order to survive.

Ample leadership qualities should be acquired in addition to being open to innovation and fostering research and development. Tactical considerations which are short-term have to be complemented by long-term and strategic decisions. Finally, strong relationships (may be exploring partnering relationships) should be developed with prospective clients, unions, and government.

Further research that incorporates a more detailed view of project management competencies such as the IPMA

Competence Baseline

could reveal new insights into technical, behavioral, as well as contextual competencies.

References

Z. Isik et al. / International Journal of Project Management 27 (2009) 629–637

[1] Hubbard DG. Successful utility project management from lessons learned. Project Manage J 1990;21(30):19–23.

[2] Chan APC, Scott D, Chan PL. Factors affecting the success of a construction project. J Constr Eng Manage 2004;130(1):153–5.

[3] Jaselskis EJ, Ashley DB. Optimal allocation of project management resources for achieving success. J Constr Eng Manage 1991;117(2):

321–40.

[4] Munns AK, Bjeirmi BF. The role of project management in achieving project success. Int J Project Manage 1996;14(2):81–7.

[5] Morris PWG, Hugh GH. Preconditions of success and failure in major projects. Templeton college. The Qxford Centre for Management Studies, Kinnington Oxford, UK, 1983; Technical Paper No. 3.

[6] Newcombe R, Langford D, Fellows R. Construction managementmanagement systems, vol. 1. London: Mitchell Publishing Co.; 1991.

[7] Shirazi B, Langford D, Rowlinson S. Organizational structures in the construction industry. Constr Manage Econ 1996;14(3):199–212.

[8] Duncan GL, Gorsha RA. Project management: a major factor in project success. IEEE Trans Power Apparatus Syst 1983;102(11):

3701–5.

[9] Kerzner H. Project management: a systems approach to planning, scheduling, and controlling. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold;

1989.

[10] Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK

Guide). Philadelphia: Project Management Institute; 2004.

[11] Arditi D, Lee DE. Assessing the corporate service quality performance of design-build contractors using quality function deployment.

Constr Manage Econ 2003;21(2):175–85.

[12] Barney J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J

Manage 1991;17(1):99–120.

[13] Porter ME. The contributions of industrial organization to strategic management. Acad Manage Rev 1981;6(4):609–20.

[14] Warszawski A. Strategic planning in construction companies. J

Constr Eng Manage 1996;122(2):133–40.

[15] Gunhan S, Arditi D. Factors affecting international construction. J

Constr Eng Manage 2005;131(3):273–82.

[16] Shenhar AJ, Dvir D. Toward a typological theory of project management. Res Policy 1996;25(4):607–32.

[17] Shenhar AJ, Levy O, Dvir D. Mapping the dimensions of project success. Project Manage J 1998;28(2):5–13.

[18] Raz T, Shenhar AJ, Dvir D. Risk management, project success and technological uncertainty. R&D Manage 2002;32(2):101–9.

[19] Bycio P, Hackett RD, Allen JS. Further assessments of Bass’s conceptualization of transactional and transformational leadership. J

Appl Psychol 1995;80(4):468–78.

[20] Howell JM, Avolio BJ. Transformational leadership, transactional leadership, locus of control and support for innovation: key predictors of consolidated-business-unit performance. J Appl Psychol

1993;78(6):891–902.

[21] Fiedler FE. Research on leadership selection and training: one view of the future. Admin Sci Quart 1996;41:241–50.

[22] Darcy T, Kleiner BH. Leadership for change in a turbulent environment. Leadership Org Develop J 1991;12(5):12–6.

[23] Hennessey JT. Reinventing government: does leadership make the difference? Public Admin Rev 1998;58(6):522–32.

[24] Saari LM, Johnson TR, McLaughlin SD, Zimmerle DM. A survey of management training and education practices in US companies.

Personnel Psychol 1988;41(4):731–43.

[25] Beatham S, Anumba CJ, Thorpe T, Hedges I. KPIs – a critical appraisal of their use in construction. Benchmarking: An Int J

2004;11(1):93–117.

[26] Kululanga G, McCaffer R. Measuring knowledge management for construction organizations. Eng Constr Archit Manage 2001;8(5):

346–54.

[27] Ozorhon B, Dikmen I, Birgonul MT. Organizational memory formation and its use in construction. Build Res Inf 2005;33(1):67–79.

[28] Fombrun C, Shanley M. What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Acad Manage J 1990;33(2):233–58.

[29] Fombrun CJ. Structural dynamics within and between organizations.

Admin Sci Quart 1986;31(3):403–21.

[30] Pries F, Janszen F. Innovation in the construction industry: the dominant role of the environment.

Constr Manage Econ

1995;13(1):43–51.

[31] Porter ME. Competitive strategy. New York: Free Press; 1980.

[32] Arditi D, Kale S, Tangkar M. Innovation in construction equipment and its flow into the construction industry. J Constr Eng Manage

1997;123(4):371–8.

[33] Globerson S. Issues for developing a performance criteria system for an organisation. Int J Production Res 1985;23(4):639–46.

[34] Letza SR. The design and implementation of the balanced business scorecard: an analysis of three companies in practice. Business Proc

Re-eng Manage J 1996;2(3):54–76.

[35] Neely A, Richards H, Mills J, Platts K, Bourne M. Designing performance measures: a structured approach. Int J Operation

Production Manage 1997;17(11):1131–52.

[36] Porter ME. How competitive forces shape strategy. Harvard Business

Rev 1979;57(2):137–46.

[37] Spence AM. Investment strategy and growth in a new market. The

Bell J Econ 1979;10(1):1–19.

[38] Kendra K, Taplin L. Project success: a cultural framework. Project

Manage J 2004;35(1):30–45.

[39] Bresnen M, Marshall N. Building partnerships: case studies of clientcontractor collaboration in the UK construction industry. Constr

Manage Econ 2000;18(7):819–32.

[40] Ahmed SM, Kangari R. Analysis of client-satisfaction factors in construction industry. J Manage Eng 1995;11(2):36–44.

[41] Arthur JB. The link between business strategy and industrial relations systems in American steel minimills. Industrial Labor Relat Rev

1992;45(3):488–506.

[42] Oz O. Sources of competitive advantage of Turkish construction companies in international markets. Constr Manage Econ 2001;19(2):

135–44.

Z. Isik et al. / International Journal of Project Management 27 (2009) 629–637

[43] Hendrickson C, Au T. Project management for construction: fundamental concepts for owners, engineers, architects and builders. NY:

Prentice Hall; 1989.

[44] Belout A. Effects of human resource management on project effectiveness and success: toward a new conceptual framework. Int J

Project Manage 1998;16(1):21–6.

[45] Chua DKH, Kog YC, Loh PK. Critical success factors for different project objectives. J Constr Eng Manage 1999;125(3):142–50.

[46] Walker DHT, Vines MW. Australian multi-unit residential project construction time performance factors. Eng Constr Archit Manage

2000;7(3):278–84.

[47] Kanji GK, Wong A. Quality culture in construction industry. Total

Quality Manage 1998;9(4):133–40.

[48] Pfeffer J. Competitive advantage through people: unleashing the power of the workforce. Boston: Harvard Business School Press;

1994.

[49] Delaney JT, Huselid MA. The impact of human resource management practices on perceptions of organizational performance. Acad

Manage J 1996;39(4):949–69.

[50] Latham M. Constructing the team. Final Report of the Government/

Industry Review of procurement and contractual arrangements in the

UK construction industry. London: HMSO; 1994.

[51] Kangari R. Risk management perceptions and trends of US construction. J Constr Eng Manage 1995;121(4):422–9.

[52] Christopher M. Logistics and supply chain management. London:

Pitman Publishing; 1992.

[53] Egan J. Rethinking construction. UK: Department of the Environment; 1998.

[54] Semple C, Hartman F, Jergas G. Construction claims and disputes: causes and cost/time overruns. J Constr Eng Manage 1994;120(4):

785–95.

[55] Kamara JM, Augenbroe G, Anumba CJ, Carrillo PM. Knowledge management in the architecture, engineering and construction industry. Constr Innov 2002;2(1):53–67.

[56] Egbu C, Sturgesand J, Bates B. Learning from knowledge management and transorganisational innovations in diverse project management environments. In: Proceedings of the 15th annual conference of the association of researchers in construction management. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool John Moores University; 1999. p. 95–103.

[57] Ringen K, Seegal J, Englund A. Safety and health in the construction industry. Ann Rev Public Health 1995;16:165–88.

[58] Sawacha E, Naoum S, Fong D. Factors affecting safety performance on construction sites. Int J Project Manage 1999;17(5):309–15.

[59] Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling.

New York: Guilford Press; 1998.

[60] Mueller RO. Basic principles of structural equation modeling. New

York: Springler-Verlag; 1996.

[61] Garver MS, Mentzer JT. Logistics research methods: employing structural equation modeling to test for construct validity. J Business

Logistics 1999;20(1):33–57.

[62] Anderson JC, Gerbing D. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach.

Psychol Bull

1988;103(3):411–23.

637

[63] Dunn SC, Seaker RF, Waller MA. Latent variables in business logistics research: scale development and validation. J Business

Logistics 1994;15(2):145–72.

[64] Hair Jr JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC. Multivariate data analysis. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1998.

[65] Cronbach LJ, Meehl PE. Construct validity in psychological tests.

Psychol Bulletin 1955;52(July):281–302.

[66] Nunnally J. Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978.

[67] Marsh HW, Balla JR, McDonald RP. Goodness of fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis: the effect of sample size. Psychol Bull

1988;103(3):391–410.

[68] Bentler PM, Yuan KH. Structural equation modeling with small samples: test statistics. Multivariate Behav Res 1999;34(2):

181–97.

[69] Jackson DL. Sample size and number of parameter estimates in maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis: a Monte Carlo investigation. Struct Equation Model 2003;8(2):205–23.

[70] Matt G, Dean A. Social support from friends and psychological distress among elderly persons: moderator effects of age. J Health

Social Behav 1993;34(3):187–200.

[71] Larson EW, Gobeli DH. Significance of project management structure on development success. IEEE Trans Eng Manage 1989;

36(2):119–25.

[72] Brown A, Adams J. Measuring the effect of project management on construction outputs: a new approach. Int J Project Manage

2000;18(5):327–35.

[73] Cooke-Davies T. The real success factors on projects. Int J Project

Manage 2002;20(3):185–90.

[74] King AW, Zeithaml CP. Competencies and firm performance: examining the causal ambiguity paradox. Strategic Manage J

2001;22(1):75–99.

[75] Child J. Organization structure, environment and performance: the role of strategic choice. Sociology 1972;6(1):1–22.

[76] Kale S, Arditi D. Competitive positioning in United States construction industry. J Constr Eng Manage 2002;128(3):238–47.

[77] Hausman A. Variations in relationship strength and its impact on performance and satisfaction in business relationships. J Business

Industrial Market 2001;16(7):600–16.

[78] Pinto JK, Mantel S. The causes of project failure. IEEE Trans Eng

Manage 1990;37(4):269–75.

[79] Dissanayaka SM, Kumaraswamy MM. Evaluation of factors affecting time and cost performance in Hong Kong building projects. Eng

Constr Architectural Manage 1999;6(3):287–98.

[80] Dainty ARJ, Cheng MI, Moore DR. Redefining performance measures for construction project managers: an empirical evaluation.

Constr Manage Econ 2003;21(2):209–21.

[81] Atkinson R. Project management: cost, time, and quality, two best guesses and a phenomenon, it’s time to accept other success criteria.

Int J Project Manage 1999;17(6):337–42.

[82] Caupin G, Knoepfel H, Morris PWG, Panenbacker O. IPMA

Competence Baseline (ICB), <http://www.12manage.com/methods_ipma_competence_baseline.html> ; 2008 [accessed 09.08].