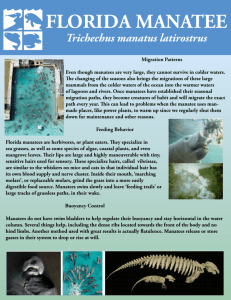

The Florida Manatee - Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation

advertisement