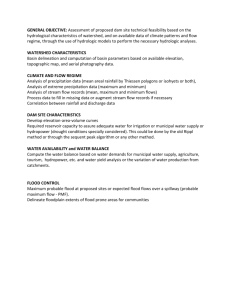

Transboundary Cooperation and Hydropower Development

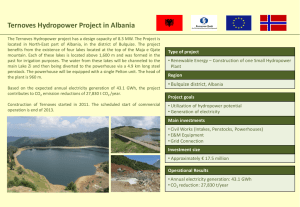

advertisement