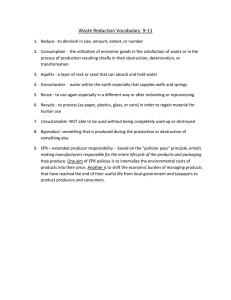

The Post-consumer Waste Problem and Extended Producer

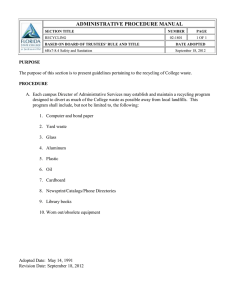

advertisement