A comparison of walk-in counselling and the wait list model for

advertisement

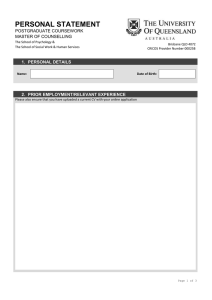

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Social Work Faculty Publications Faculty of Social Work 12-15-2015 A comparison of walk-in counselling and the wait list model for delivering counselling services Carol Stalker Wilfrid Laurier University, cstalker@wlu.ca Manuel Riemer Wilfrid Laurier University Cheryl-Anne Cait Wilfrid Laurier University Susan Horton University of Waterloo Jocelyn Booton Wilfrid Laurier University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/scwk_faculty Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Stalker C.A., Riemer, M., Cait, C.A., Horton, S., Booton, J., Josling, L., Bedggood, J. & Zaczek M. (2015). A comparison of walk-in counselling and the wait list model for delivering counselling services. Journal of Mental Health. Published on-line: 15 December 2015. DOI:10.3109/09638237.2015.1101417. This study was funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) FRN 119528. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty of Social Work at Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Social Work Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact scholarscommons@wlu.ca. Authors Carol Stalker, Manuel Riemer, Cheryl-Anne Cait, Susan Horton, Jocelyn Booton, Leslie Josling, Joanna Bedggood, and Margaret Zaczek This article is available at Scholars Commons @ Laurier: http://scholars.wlu.ca/scwk_faculty/16 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL Thisisthepre-peer-reviewedversionofthefollowingarticle: StalkerC.A.,Riemer,M.,Cait,C.A.,Horton,S.,Booton,J.,Josling,L.,Bedggood,J.&Zaczek M.(2015).Acomparisonofwalk-incounsellingandthewaitlistmodelfordelivering counsellingservices.JournalofMentalHealth.DOI:10.3109/09638237.2015.1101417, whichwaspublishedon-lineonDecember15,2015.See http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/09638237.2015.1101417 ThisstudywasfundedbyCanadianInstitutesofHealthResearch(CIHR)FRN 119528. 1 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL Runninghead:WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL Acomparisonofsingle-sessionwalk-incounsellingandthe traditionalmodelfordeliveringcounsellingservices CarolA.Stalker1,ManuelRiemer2,Cheryl-AnneCait3,SusanHorton4, JocelynBooton5,LeslieJosling6,JoannaBedggood7andMargaret Zaczek8 1Professor,FacultyofSocialWork,WilfridLaurierUniversity 2AssociateProfessor,DepartmentofPsychology,WilfridLaurierUniversity 3AssociateProfessor,FacultyofSocialWork,WilfridLaurierUniversity 4Professor,CentreforInternationalGovernanceInnovation,ChairinGlobalHealth Economics,UniversityofWaterloo 5ResearchCoordinator,FacultyofSocialWork,WilfridLaurierUniversity 6ExecutiveDirector,KWCounsellingServices,Kitchener,Ontario 7ClinicalDirector,KWCounsellingServices,Kitchener,Ontario 8DirectorofCommunityCounsellingProgram,FamilyServiceThamesValley,London, Ontario ThestudywasconductedatKWCounsellingServices,Kitchener,OntarioandFamily ServiceThamesValley,London,Ontario. WordCount:3,969wordsexcludingAbstract,References,TablesandFigure. *RequestsforreprintsshouldbeaddressedtoCarolStalker,FacultyofSocialWork,WilfridLaurier University,120DukeSt.W.,Kitchener,OntarioN2P2B3Canada.E-mail:cstalker@wlu.ca Telephone:519-896-7585.Fax:519-888-9732. 2 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL AComparisonofSingle-SessionWalk-inCounsellingandtheTraditionalModelfor DeliveringCounsellingServices Abstract Background:Walk-incounsellinghasbeenusedtoreducewaittimesbuttherearefew controlledstudiestocompareoutcomesbetweenwalk-inandthetraditionalmodelof servicedelivery. Aims:Tocomparechangeinpsychologicaldistressbyclientsreceivingservicesfromtwo modelsofservicedelivery,awalk-incounsellingmodelandatraditionalcounsellingmodel involvingawaitlist Method:Mixedmethodssequentialexplanatorydesignincludingquantitativecomparison ofgroupswithonepre-testandtwofollowups,andqualitativeanalysisofinterviewswith asubsample.524participants16yearsandolderwererecruitedfromtwoFamily CounsellingAgencies;theGeneralHealthQuestionnaireassessedchangeinpsychological distress;prioruseofothermentalhealthandinstrumentalserviceswasalsoreported. Results:Hierarchicallinearmodellingrevealedclientsofthewalk-inmodelimproved fasterandwerelessdistressedatthe4-weekfollow-upcomparedtothetraditionalservice deliverymodel.Atthe10-weekfollow-up,bothgroupshadimprovedandweresimilar. Participantsreceivinginstrumentalservicespriortobaselineimprovedmoreslowly. Qualitativeinterviewsconfirmedparticipantsvaluedtheaccessibilityofthewalk-inmodel. Conclusions:Thisstudyimprovesmethodologicallyonpreviousstudiesofwalk-in counselling,anapproachtoservicedeliverythatisnotconducivetorandomizedcontrolled trials. 3 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL Declarationofinterest:None. Keywords:single-sessiontherapy;walk-incounselling;outcomes;hierarchicallinear modeling;mentalhealthtreatment;servicedeliverymodels;mixedmethods;brieftherapy 4 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL Longwaitinglistsformentalhealthservicesarecommon.Community-basedmental healthandfamilycounsellingagencieshaveincreasinglyturnedtothewalk-incounselling (WIC)modeltoreducewaittimesandimproveaccessibility.Mostwalk-incounselling servicesprovidesinglesessiontherapy(SST),whichhasbeendefinedas“anyone-visit treatmentthatisintendedtobepotentiallycompleteuntoitself”(Hoyt,1994,p.141).SST canbeofferedbyappointmentorwithinawalk-incounsellingprogram. NosingletheoreticalframeworkguidesSST;however,itisbasedonprinciplesof brieftherapythatencouragetherapiststolistencarefullytotheclient’sgoalsandto emphasizetheclient’sstrengthsandresources.Systemic,narrative,solution-focusedand cognitivebehavioralapproachesarefrequentlyusedinSST(Campbell,2012;Clements, McElheran,Hackney,&Park,2011;Young,2011).OrganizationsofferingWICusually provideadditionalcounsellingtoclientswhorequestitorareassessedbythetherapistto requireit. AlthoughSSThasbeenemployedtocopewithwaitlistsformanyyears(Denner& Reeves,1997;Clementsetal.2011),andafewdescriptivestudiesofwalk-incounselling servicesthatemploySSThavebeenpublished(authors,2013),wefoundonlyoneprevious studyofWICwithastandardizedmeasureofclinicaloutcomeandacomparisongroup (withawaitlist)(Barwicketal.,2013).ChildrenandtheirfamiliesusingWIChad“steeper ratesofimprovementcomparedtousualcareclientsdespiteequivalenceinpsychosocial functioningatbaseline”(p.339). OnestudyofSSTbyappointmentwasfoundwitharandomizedcontrolgroupanda standardizedoutcomemeasure(Perkins,2006).Youthandtheirparentswhoattendeda scheduledsinglesessionwithintwoweeksoftheirrequestinanoutpatientmentalhealth 5 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL clinicinAustralia,werecomparedwithcontrolswhoreceivedtheSSTsessionaftera6weekwait.Significantimprovementinseverityandfrequencyofpresentingproblemfor thetreatmentgroupwasreportedcomparedtothecontrolafter6weeks.Reviewsofthese studieshaveconcludedthatSSTmaybehelpfulforsomeclients,butmorerigorous researchisneeded(Bloom,2001;Cameron,2007;Campbell,2012;authors,2013;Hurn, 2005). Recruitmentandretentioninnaturalisticstudiesofclientsseekingpsychotherapy aredifficult(Staines&Cleland,2007),butthecharacteristicsofWICmayexacerbatethis challenge.Designingstudieswithcontrolorcomparisongroupsthataresimilartoclients whoattendWICisdifficult,inpart,becauseofthelikelihoodthatclientsself-selectwhen bothwalk-incounsellingclinicsandtraditionalservicemodelsareavailable.Givenachoice, individualsandfamilieswhoarehighlydistressedwouldbeexpectedtoattendawalk-in counsellingserviceratherthanseekserviceswherewaitlistsarethenorm. WeaimedtocomparepsychologicaloutcomesforclientsofaWICserviceoffering SST,withclientsonawaitlistfortraditionalcounseling.Wehypothesizedthatclientswho accessedtheWICmodelwouldshowfasterimprovementinpsychologicaldistressthan thosewhoaccessedthetraditionalservicedeliverymodelusuallyinvolvingawaitlist.A secondobjectivewastounderstandwhomaybenefitmostfromthismodel. Method Weemployedamixedmethodssequentialexplanatorydesign(Ivankova,Creswell, &Stick,2006)collectingquantitativedatainthefirstphase,andqualitativedatainthe secondphase.TheUniversityResearchEthicsBoardapprovedthestudy. 6 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL AgencySettings DatawerecollectedfromtwoFamilyCounsellingagenciesintwourbanareas located97kilometresapartandsimilarintermsofpopulation.FamilyServiceAgencyA introducedaWalk-inCounsellingClinic(WICC)in2007.Theclinicisopenonedayper weekfromnoonuntil6:00p.m.withthelastclientdepartingatapproximately8:00p.m. ThenumberofpeopleattendingtheWICCeachdayrangesfrom29to75;40to50people perdayismostcommon.Anyindividual,coupleorfamilymayattendwithoutan appointment.Clientsregisterwiththereceptionistandpayafee,whichisonaslidingscale gearedtoincomerangingfromnochargetoCA$187.50($125.00perhour).Theintake workerwhoscreensforrisktoselforothers,addictionsandintimatepartnerviolence,sees theclient(s)briefly.Theclient(s)seesatherapistforasessionnormallylastingupto90 minutes.Thetherapistemploysastrengths-basedapproachthatinvolvescollaboration withtheclient(s)todevelopawrittenplan.Clientsareencouragedto“worktheplan”and toreturntotheWICC(orrequestongoingcounselling)ifneeded. AtFamilyServiceAgencyB,whichdoesnothaveawalk-incounsellingclinic, betweeneightand15peoplenormallytelephoneeachbusinessdayrequestingcounselling, buttheagencyisonlyabletoprovidethreetofivetelephoneintakeappointmentsperday. Individualswhocallearlyenoughtobeincludedinthedailyquotaaregivenatelephone appointmentwithanIntakeWorker,normallywithinafewdays.TheIntakeWorker determinestheserviceoffered,usuallyplacingthecalleronawaitlist.TheIntakeworker alsoinformscallersaboutothercommunityservicesthatmaybehelpfultothem.People callingafterthedailyquotahasbeenreachedareaskedtocallbackthenextbusinessday. Whengivenanappointmentforongoingcounselling,thecosttotheclientisgearedto 7 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL incomeandrangesbetweennochargeandCA$115.00perone-hoursession.Noother agencyinthatcityofferedWICatthattime. Priortodatacollection,wedeterminedthatclientswhoattendedtheWICCand thosewhorequestedcounsellingfromthecomparisonagencywereareasonablematch demographically,andthetwoagenciesofferedasimilarrangeofotherservices. RecruitmentProcedure Phase1 AttheWICC,everyoneaged16yearsandolderwhorequestedservicewasinvited bythereceptioniststoparticipateinthestudy,andgiventheBaselineQuestionnaire. ResearchAssistants(RAs)presentinthewaitingroomofferedtoassistifaclientneeded helptocompletethequestionnaire.Participantsprovidedcontactinformationandconsent forfollow-upbytelephonealongwiththecompletedquestionnaire. Atthecomparisonagency,thereceptionistswhoreceivedcallsrequesting counsellingrespondedasusual;beforeterminatingthecalltheyinvitedcallers16yearsor oldertoparticipateintheresearch.Severalmonthsintothestudy,tobesurethatall clientswereinformedaboutthestudy,weintroducedasupplementarystep.TheIntake Worker,whencallingbackinresponsetotheinitialrequest,wasalsoaskedtoexplainthe studyandinvitethecallertoparticipate.CallersconsentingtospeakwiththeRAwere eithertransferredimmediatelytotheon-siteRAoraskedforcontactinformationsotheRA couldcallthemlater.TheRAsexplainedthestudyandthecaller’srightsandrequested verbalconsenttoparticipateinthestudy.Forthosewhoconsented,theRArecordedthe participant’sanswerstothebaselinequestions. 8 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL Bothgroupswerere-interviewedbytelephonefourand10weeksaftertheinitial questionnaire.Asanexpressionofappreciation,participantsweremaileda$10coffeeshop giftcardwhentheycompletedthe4-weekfollow-uptelephoneinterviewsandagainafter the10-weekfollow-uptelephoneinterviews.Afterthe10-weekfollow-up,consenting participantswereconsideredforinclusioninrecruitmentforthesecondphaseofthestudy. Phase2 Thequalitativecomponentwasdirectedbyamultiplecasestudyapproach comparingtwodifferentmodelsofserviceprovision(Drisko,2004,Stake,1995,Yin,2003). Thecasestudysoughttounderstandaspectsoftheservicedeliverymodelsclientsfound bothhelpfulandunhelpful. Participantswereselectedaccordingtothreecategorieswith respecttotheirscoresovertimeontheoutcomemeasure(GeneralHealthQuestionnaire12(GHQ-12)(Goldberg,1972);becausetheoveralltrendforparticipantsfrombothsites wasimprovementontheGHQ-12,thethreecategorieswere“trend(improvement)”,“nontrend(nochange)”and“non-trend(deterioration)”.Atotalof48interviewswere conducted.Participantsreceivedanother$10giftcardwhentheycompletedthequalitative interview. Measures Participantsprovideddemographicinformationandselectedpresentingproblem(s) fromalistofcommonconcernsthatleadadultstoseekmentalhealthcounselling.The GHQ-12isa12-itemscaledevelopedasaself-administeredscreeninginstrumentto identifypsychologicaldistress.Itwasdesignedforuseingeneralpopulationsurveysorin clinicalsettings(McDowell,2006).Ithasbeentranslatedintomanylanguagesandfound tobereliableandvalidthroughouttheworld.Itcorrelateshighlywithmeasuresofwell- 9 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL beingandothermeasuresofdistress,andhasdemonstratedabilitytopredictphysician visitsandpsychiatricconsultations.Sensitivitytochangeisgood(Goldberg,1972).We usedtheLikert-typescalescores(1-4)becausetheyhavebetterdistributionalproperties forlongitudinalstudiesofchangecomparedtothemorecommonGHQscoring,developed primarilyforscreeningpurposes.Scoresrangefrom0-36. Tomeasureprioruseofsocialandmentalhealthservices,inconsultationwiththe agencypartners,wedevelopedameasuretailoredtotheuniquecontextofeachagency. Thismeasurelistedlocalagenciesprovidingmentalhealthcounsellingandinstrumental support.Thelatterincludedagenciesprovidingassistancerelatedtohousing,employment, familyviolence(e.g.women’sshelters)andlegalissues.Participantswereaskedtoindicate thosewithwhichtheyhadcontactandthenumberofvisitsorcontactsintheprevious month.Theywereinvitedtoaddanyagenciesthatwerenotinthelist.Thisformat followedrecommendationsofresearcherswhohavestudiedreliablewaystocollectthis typeofdata(Reid,Toban&Shanley,2007). Toestimatethecost-effectivenessofthetwomodelsofservicedelivery,participants wereaskedabouttheirabilitytoparticipateindailyactivities/workandabouttheiruseof formalhealthservicesinthepreviousmonth.Thefindingsrelatedtocost-effectivenessare reportedinaseparatepaper. Anoriginalsemi-structuredinterviewguidewasdevelopedforthequalitative telephoneinterviews,whichlasted20to30minutes.Theinterviewgathered comprehensiveinformationabouttheparticipants,includingpresentingproblem,natureof psychologicaldistress,thecounsellortheymetwith,howeachservicehadorhadnotbeen helpful,otherservicesused(ornot)andreasonsforalternativeserviceuse.Itincluded 10 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL open-endedquestionsandplannedpromptstomeettheneedsforbothstructureand consistencyintheinterview(McCracken,1988). DataAnalysis Phase1QuantitativeDataAnalysis Totestthemainhypothesis,weusedhierarchical,longitudinal,slopes-asoutcome modelsthatusedrandomcoefficientstoestimatewhetherthewalk-inmodelhada differentialeffectonindividuals’trajectories.Inthishierarchicallinearmodel(HLM;also referredtoasmultilevelmodelormixedeffectsmodel),repeatedmeasureswerenested withinparticipantsandtheeffectofthewalk-inmodelwasestimatedasasecondlevel dummyvariable(Singer&Willet,2003;Raudenbush&Bryk,2002).Whilesomestudies alsoincludetheclinicianasalevelintheHLMmodel,thiswasnotfeasibleinthisstudy becausenotallclientsinthecomparisongroupsawaclinicianduringthestudyperiod.We usedSAS,ProcMixedV9.2,toestimatethemodelbyusingrestrictedmaximumlikelihood (RML)estimationasrecommendedformulti-levelmodelsifrepeatedmeasuresarenot equallyspaced(Singer&Willet,2003). HLMsofferimportantadvantagescomparedtooldermodels,suchasbetter handlingofmissingvaluesandunequaltimeintervalsbetweenandwithinparticipant responses(Hedeker&Gibbons,1997;Nich&Carroll,1997).Repeatedmeasurementsalso increasethestatisticalpower,describetheshapeofchangeovertime,andavoidthe psychometricproblemsassociatedwithchangesinscoresbeforeandafteranintervention. Indevelopingthefinalmodelpresentedbelow,age,genderandpriorserviceuse (mentalhealthandinstrumentalservices)duringthefourweekspriortothebaseline assessmentwereenteredintothemodelascontrolvariableswiththeGHQ-12scoreasthe 11 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL dependentvariable.Theagevariableiscenteredontheaverageageof35whilegenderis representedasadummyvariable(Female=1;MaleorTransgender=0).Priormentalhealth serviceuserepresentsthenumberofreportedmentalhealthservicesreceivedorattempts ataccessingtheseservices(e.g.,counsellingsessionsorcallstoacrisisservice)inthe monthpriortobaseline.Whileonlythegendervariablewassignificantlydifferentbetween thegroupsatbaseline,themaineffectsofallcontrolvariableswereretainedinthemodel fortheoreticalreasons.Theindividualtrajectoryismodeledasaquadraticgrowthmodel includingbothalinearcomponentrepresentingtheinitialslopeatbaselineandaquadratic componentrepresentingthecurvatureoraccelerationineachtrajectory(Raudenbush& Bryk,2002).Group(1=WICC)wasenteredasasecondleveldummyvariabletoaccountfor theeffectofthewalk-inmodelrelativetoatraditionalmodel. Phase2QualitativeAnalysis Transcriptionsofthetelephoneinterviewswerereviewedforaccuracybefore analysisbegan.Amultiplecasestudyapproachinvolvesanalysisbothwithineachcase (model)andacrosscases(models)(Stake,1995,Yin,2003).Athematicanalysiswas conducted,organizingdataintopatterns/themes,andincludingacross-thematicanalysis. Codinginvolvedfivephases:becomingfamiliarwiththedata,creatinginitialcodes, assemblingcodesintothemes,naminganddefiningthemes,andfinally,integrating qualitativefindingswithquantitativefindingstoanswertheresearchquestions(Lofland& Lofland,1984).Themeswereidentifiedbothinductivelyanddeductively.Trustworthiness, credibilityandverificationofdatawereestablishedthroughintercoderagreement(3 coders),lengthyandrigorousdiscussionsidentifyingareasofdifferencetoreachclarityon 12 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL codes,memo-takingandfurthersampling(interviewing)(Miles&Huberman,1994). Themesrepresentrepeatedinstancesofsimilarresponsesacrossthedata. Results Participants AttheWICC,outofanestimated729individualswhoattended,359(49%) completedthebaselinequestionnaire;307ofthe359(85.5%)consentedtofollow-up.Of these,221(72%ofthoseconsentingtofollow-up)completeddatacollectionatthe4-week follow-up,and229(75%)completedthedatacollectionatthe10-weekfollow-up.Atthe comparisonagency,outofanestimated532eligibleindividualswhorequestedcounselling, 151individuals(28%)completedthebaselinedatacollectionandalloftheseagreedto follow-up.At4weeksfollow-up,146ofthe151(97%)completedthedatacollectionandat 10weeks,142(94%)completedthedatacollection. [Table1approximatelyhere] Table1illustratesdemographicandothercharacteristicsoftheparticipantsfrom eachresearchsite.Thetwosamplesweresimilarwithrespecttotheproportionbornin CanadaandtheproportionforwhichEnglishwasthefirstlanguage.Theparticipants attendingtheWICCweremorelikelytobemale,andslightlyyoungerthanthecomparison group.Similarproportionsatbothsiteswereemployedfull-timeorunemployed,butthose attendingtheWICCweremorelikelytoreportattendingschoolandlesslikelytoreport beingoneitherSocialAssistanceortheprovincialdisabilitysupportprogram. ThemeanGHQ-12scorefortheWICCparticipantsatbaselinewasslightlyhigher thanforthecomparisongroup.Reporteduseofmentalhealthandinstrumentalsupport 13 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL servicesinthefourweekspriortobaselinewassimilar,althoughthecomparisonagency participantsreportedslightlymorepriorcontactswithothermentalhealthorganizations. FormalmentalhealthservicesincludevisitstotheEmergencyRoomand/oradmissionsto hospitalformentalhealthreasons. HierarchicalLinearModelling [Table2approximatelyhere] TheestimatesforthefinalmodelcanbeseeninTable2.TheHLManalysisconfirms ourhypothesisthatparticipantsintheWICCgroupimprovedfasterthanparticipantsinthe comparisongroup.Thereisasignificantmaineffectofgroup(2.05),suggestingthat,on average,participantsintheWICCgroupweremoredistressedatbaseline.Theslope coefficientfortime(-1.61)indicatesthatimmediatelyafterthebaselineassessment, participantsinthecomparisongroupimprove,onaverage,1.61pointsontheGHQ-12per week.Thesignificantinteractioneffectofgroupandtime,however,suggeststhatthesame rateforparticipantsintheWICCgroupis-3.05,almostdoubletherateofthecomparison group.However,overtime,thisdifferenceingrowthratesbecomeslesspronounced(see Figure1).Throughaseriesofmodelcomparisonsitwasdeterminedthatinadditionto group(walk-invs.traditional),instrumentalsupportserviceusepriortobaselinewas relatedtoindividualchangesinGHQ-12scoresovertimebuttheinteractionforageand genderwasnotsignificant.Noneofthethree-wayinteractionswithtime,groupandthe controlvariablesweresignificant. [Figure1approximatelyhere] Figure1depictsthedifferencebygroupinGHQ-12scoresovertime(Week0-10)as predictedbythestatisticalmodelforfemaleclientsattheaverageageof35withno 14 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL instrumentalserviceuseinthefourweekspriortobaseline.Theseconditionswere selectedtorepresentthemosttypicalcases.ThemodelpredictsthattheWICCgroup participants,onaverage,wouldtransitionfromaclinicalseverityleveltoanormalor nonclinicalrange(i.e.,aGHQ-12scoreof13orless)afterfiveweekswhiletheaverageof thecomparisongroupwouldnotreachthisclinicalthresholduntilweek10.Forthetypical casesdescribedabove,theestimatedeffectsizeatfourweeksis0.24,whichisconsidereda smalleffect(Cohen,1992).At10weeks,theeffectsizeisonly0.05.Effectsizeswere calculatedusingthepooledstandarddeviationoftherawscoresassuggestedforgrowth models(Feingold,2009). QualitativeFindings Participants’narrativesabouttheirexperienceswithwalk-inand/ortraditional counsellinghelpedusbetterunderstandfindingsfromthequantitativedata,inparticular differencesbetweenthetwomodelsintherateofchangeandforwhomwalk-in counsellingishelpful.Aparticipant’sjourneythroughandexperiencewithbothmodelsof counsellingwascharacterizedinfourinterconnectedways.Oneofthese,Accessibility (barriersand/orfacilitatorsinfluencingaperson’sabilitytoreceiveandobtainservices)is mostsalientinunderstandingthedifferenceinrateofchange.Beingabletoaccessservice quicklyandeasilywasveryimportanttoparticipantswhoutilizedtheWICC:“Itwas definitelysomethingIliked.Iamgladthiswasanoptionforme.FromhowitwasbeforeI hadtokeeplookingtofindacounsellor”.AnotherWICCparticipantexplained,“itwasnice, because...whenyouhavethesethingsonyourmindyoukindofwanttogetitoffright away.”Thisstandsindirectcontrasttoaparticipantattemptingtoaccessservicesforboth herselfandheradolescentdaughterfromthetraditionalmodel,“Imean,shewasinthe 15 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL mindsettogoandprobablyifwehadbeenabletogetanappointmentthatweek,yesit probablywouldhavemadeadifferencebecauseshewasgoingtogo,...Ican’tremember exactlywhattranspiredinthatperiodoftime(whileonawaitlist),butshechangedher mind.” AccessibilityislinkedtoMeaningofService,aparticipant’swayofmakingsenseof theirexperienceandunderstandingoftheservicereceived.Thefollowingparticipant explainshowtheeaseofaccessibilityfortheWICChelpedtomobilizeherandthisledtoa senseofselfefficacy:“SoImeanIhavealotofissues.Idon’tknowifanyonecan really…youknowsaytheperfectthingthatisgoingtomakethemgoaway…whetherit’s fatiguefromMS(MultipleSclerosis)orpainfromwhateverorjustfeelinganxietyandjust depressionandworthlessness.Idon’twanttogooutside…justgoingoutofthehousethat dayIfeltreallygood…So,I’m,like,okay,I’mgoingtodothisandIwasscaredasshit leavingbutIfeltgoodaboutitforjustthat.Gettingthatdone,no,IfeltalotbetterafterIleft [theWICC].Ifeltlikeshe[counsellor]wasveryhelpfulandgavemeencouragementtodo thingsandthatiskindofhardforme.So,tosaythatshehelpedmewiththat,thatwas prettycool.” ReadinessforService,thedegreetowhichtheparticipantfeelsmotivatedandableto committoandengageincounselling,helpsusunderstandtheeffectivenessoftheWICC andforwhomitisbeneficial:“ItrunsinmyfamilythereisalotofpeoplewhohavebipolarandalotofdepressionandanxietyandIjust,...IfiguredI’mnotgoingtotakea chanceI’mgoingtodoitmyselfandIwantedtoseeifIcouldgetsomeadvicefrom somebodyelseandseeiftheycouldoffersomesortofcopingmethodsthatIcouldutilize 16 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL tocopewhenIfindmyselfstressingout.So,Idecidedtowalk-inandsee,Iguess,whatI couldlearnandwhatIcouldapply.” Discussion ThisstudyadvancesresearchontheWICservicedeliverymodelbyemployinga comparisongroup,usingastandardizedmeasure,recruitinglargersamples,including follow-upto10weeks,usingHLMtoanalyzethequantitativedataandusingamixed methodsdesign.Anotherstrengthistherelativelyhighparticipantretentionrateacross thefollow-uppoints. TheresultsoftheHLManalysisconfirmourhypothesisthatparticipantsinthe WICCgroupimprovedfasterthanparticipantsinthecomparisongroup.Theimprovements inseverityofdistressaresignificantlydifferentinthefirstfewweeksfollowingtheinitial contactwiththeagencies.Towardtheendofthetenweeks,themeanGHQ-12scoresfor bothgroupsaresimilareventhoughtheinitialconditionalmeanGHQ-12scoreforthe WICCgroupwas2.05pointshigher.Thestudysupportsthefindingsofless methodologicallyrigorousstudiesofsinglesessiontherapyandwalk-incounsellingthat reportedimprovementinthepresentingproblemfollowingeitherascheduledsingle sessionorvisittoawalk-incounsellingservice(Authors,2013). Clientswhowerereceivingmoreinstrumentalsupportservicesinthefourweeks priortorequestinghelpatbothagenciesimprovedataslightlyslowerratethanthosenot reportinginstrumentalsupportservicesatbaseline.Peoplewhoarereceivinghelpwith problemslikehousingorfamilyviolencemaybelesslikelytoimprovequicklybecause,for example,itnormallytakessomeperiodoftimetofindsuitablehousing,andthecomplexity 17 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL ofdecisionsinvolvingfamilyviolencearewellknown.Prioruseofinstrumentalsupport servicesmayalsobeanindicatorofpoverty,arecognizedsocialdeterminantofhealth. Findingsfromtheinterviewsindicatethatforsomeclientsofthewalk-inmodel, mentalhealthdifficultiesareanongoingpartoftheirlifeexperience,somethingtheyneed tonegotiateandadapttoatdifferentlifestages.Forthesepeople,beingabletohavea “booster”intheformofaneasilyaccessiblewalk-insessionisnotonlyhelpfulintermsof relievingdistress,butalsoagoodfitforthosenotinterestedinongoingcounselling.The interviewsalsorevealedthathowparticipantsmakesenseoftheirexperienceandhow readytheyaretousecounsellingservicesmayinfluencewhobenefitsmostfromwalk-in counselling. ThefindingthatproportionatelymoremenaccessedtheWICCissimilartofindings fromBarwicketal.’s(2013)studyofchildrenandyouthattendingwalk-incounselling; theyreportedmoremalesweretheinformantsforchildrenseeninthewalk-inclinicthan intheusualcarecondition.Futureresearchcouldclarifywhetherthewalk-incounselling modelisabettermatchthanthetraditionalmodelwiththehelp-seekingneedsofsome men(Evans,Frank,Oliffe&Gregory,2011). Limitationsofthestudyincludethedissimilarmodeofdatacollectionbetweenthe sitesatbaseline(self-reportvstelephoneinterview)anddifferentialparticipationrates. Althoughmulti-levelmodelingenabledustocontrolforthedifferencebetweensitesinthe meanGHQ-12scoreatbaseline,moresimilarityintermsofinitiallevelofdistressand genderwouldstrengthenthestudy. Thestudydemonstratesthatindividualsattendingwalk-incounsellingservicesare willingtoparticipateinoutcomeresearch,andwithsufficientresourcesandadequate 18 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL trainingofresearchstaff,itispossibletoachieveagoodresponserate.Moreresearch involvingmultiplewalk-incounsellingservicesandadditionalcomparisonservicesis neededtoconfirmthefindingsofthisstudyandtounderstandinmoredetailtheessential componentsofaneffectivewalk-incounsellingservice. 19 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL References Barwick,M.,Uranjnik,D.,Sumner,L.,Cohen,S.,Reid,G.,Engel,K.&Moore,J.E.(2013). Profilesandserviceutilizationforchildrenaccessingamentalhealthwalk-inclinic versususualcare.JournalofEvidence-BasedSocialWork,10,338-352. Bloom,B.L.(2001).Focusedsingle-sessionpsychotherapy:Areviewoftheclinicaland researchliterature.BriefTreatmentandCrisisIntervention,1(1),75–86. Cameron,C.L.(2007).Singlesessionandwalk-inpsychotherapy:Adescriptiveaccountof theliterature.CounsellingandPsychotherapyResearch,7(4),245–249. Campbell,A.(2012).Single-sessionapproachestotherapy.TheAustralianandNewZealand JournalofFamilyTherapy,33,(1),15-26. Clements,R.,McElheran,N.,Hackney,L.&Park,H.(2011)TheEastsideFamilyCentre:20 yearsofsinglesessionwalk-intherapy.InSlive,A.&Bobele,M.(Eds.)Whenone hourisallyouhave:Effectivetherapyforwalk-inclients.pp.109-127.Phoenix,AZ: Zeig,Tucker&TheisenInc. Denner,S.&Reeves,S.(1997).Singlesessionassessmentandtherapyfornewreferralsto CMHTS.JournalofMentalHealth,6(3),275-280. Drisko,J.(2004).InD.Padgett(Ed.),Thequalitativeresearchexperience,pp.100-121. Belmont,California:Thomson. Evans,J.,Frank,B.,Oliffe,J.L.&Gregory,D.(2011).Health,illness,menandmasculinities (HIMM):atheoreticalframeworkforunderstandingmenandtheirhealth.Journalof Men’sHealth,8(1),7-15. Feingold,A.(2009).Effectsizesforgrowth-modelinganalysisforcontrolledclinicaltrialsin thesamemetricasforclassicalanalysis.PsychologicalMethods,14(1),43-53. 20 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL Goldberg,D.P.(1972).Thedetectionofpsychologicalillnessbyquestionnaire.London: OxfordUniversityPress. Hedeker,D.&Gibbons,R.D.(1997).Applicationofrandom-effectspattern-mixturemodels formissingdatainlongitudinalstudies.PsychologicalMethods,2,64–78. Hoyt,M.F.(1994).Singlesessionsolutions.InM.F.Hoyt(Ed.)Constructivetherapies.(pp. 140-159).London:GuilfordPress. Hurn,R.(2005).Single-sessiontherapy:Plannedsuccessorunplannedfailure?Counselling PsychologyReview,20(4),33–40. Ivankova,N.V.,Creswell,J.W.&Stick,S.L.(2006).Usingmixed-methodssequential explanatorydesign:Fromtheorytopractice.FieldMethods,18(1)3-20. Lofland,J.&Lofland,L.H.(1984).Analyzingsocialsettings.BelmontCA:Wadsworth PublishingCompanyInc. McCracken,G.(1988).Thelonginterview.BeverlyHills:Sage.McDowell,I.(2006). Measuringhealth McDowell,I.(2006).Measuringhealth:Aguidetoratingscalesandquestionnaires.New York:OxfordUniversityPress. Miles,M.B.&Huberman,A.M.(1994).Qualitativedataanalysis.BeverlyHills,CA:Sage. Nich,C.&Carroll,K.(1997).Nowyouseeit,nowyoudon’t:acomparisonoftraditional versusrandom-effectsregressionmodelsintheanalysisoflongitudinalfollow-up datafromaclinicaltrial.JournalofConsultingandClinicalPsychology,65,252–261. Perkins,R.(2006).Theeffectivenessofonesessionoftherapyusingasingle-session therapyapproachforchildrenandadolescentswithmentalhealthproblems. PsychologyandPsychotherapy:Theory,ResearchandPractice,79(2),215–227. 21 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL Price, C. (1994). Open days: Making family therapy accessible in working class suburbs. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 15(4), 191–196. Raudenbush,S.W.&Bryk,A.S.(2002).Hierarchicallinearmodels:Applicationsanddata analysismethods.ThousandOaks,Calif:Sage. Reid,G.I.,Toban,J.I.&Shanley,D.C.(2008)Whatisamentalhealthclinic?Howtoask parentsabouthelp-seekingcontactswithinthementalhealthsystem. AdministrationandPolicyinMentalHealth35,241–249. Shadish,W.R.,Cook,T.D.&Campbell,D.T.(2002).Experimentalandquasi-experimental designsforgeneralizedcausalinference.Boston:HoughtonMifflin. Singer,J.D.&Willett,J.B.(2003).Appliedlongitudinaldataanalysis:Modelingchangeand eventoccurrence.NewYork:OxfordUniversityPress. Stake,R.E.(1995).Theartofcasestudyresearch.ThousandOaks,California:Sage. Staines,G.L.&Cleland,C.M.(2007).Biasinmeta-analyticestimatesoftheabsoluteefficacy ofpsychotherapy.ReviewofGeneralPsychology,11(4)329-347. Yin,R.K.(2003).Casestudyresearch(3rded.).ThousandOaks,California:Sage. Young,K.(2011).Narrativepracticesatawalk-intherapyclinic.InSlive,A.&Bobele,M. (Eds.)Whenonehourisallyouhave:Effectivetherapyforwalk-inclients.pp.149166.Phoenix,AZ:Zeig,Tucker&TheisenInc. 22 WALK-INCOUNSELLINGVSTRADITIONAL Figure1 EstimatedGHQ-12ScoresforEachGroupOverTime(for35yearoldfemaleclientswithno priorserviceuse) 35 30 25 GHQ12Scores Transitionfromclinicalto normalrange 20 15 10 Comparison 5 Walk-In Treshold 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Weeks 23