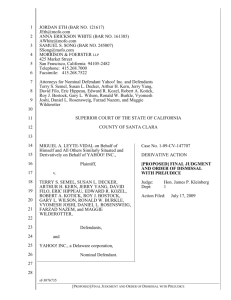

Example of Electronic Courtesy Copy - Ninth Judicial Circuit Court of

advertisement