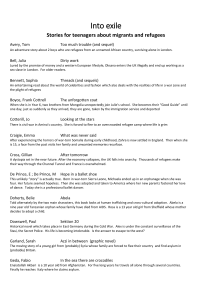

The move-on period: an ordeal for new refugees

advertisement