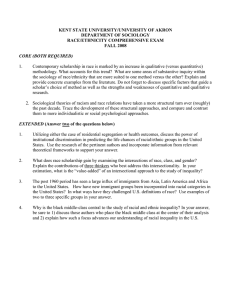

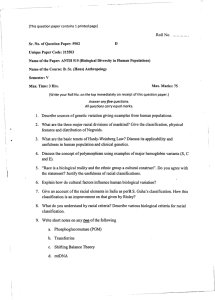

Chapter 14 -- Racial inequality-

advertisement