How Ideology Trumped Science - Council for Global Equality

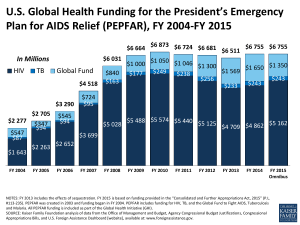

advertisement