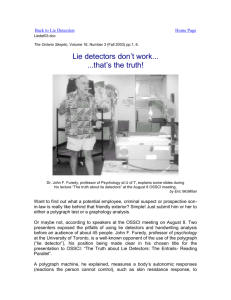

The Legal Implications of Graphology

advertisement