THE EFFECTS OF VARIABLES IN ORAL HISTORY: PALM BEACH

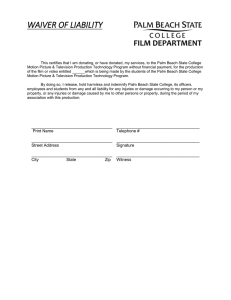

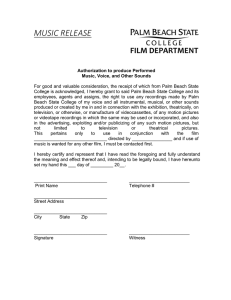

advertisement