Member-State Principals, Supranational Agents, and

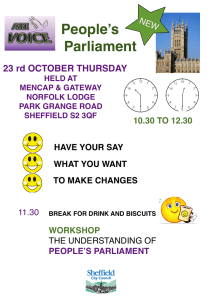

advertisement