Last Updated: July 2013

Federal Update: September 2012

NORTH CAROLINA INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

Womble Carlyle Sandridge & Rice, LLP

Foley Hoag LLP (Federal)

Julia Huston, Joshua S. Jarvis,

Jenevieve J. Maerker, and Philip C. Swain

Table of Contents

1. Overview

2. Copyrights

3. Trademarks & Service Marks

4. Trade Names

5. Trade Secrets

6. Patents

7. IP Resources

1. Overview

There is often a tradeoff between the widespread dissemination of solutions to intractable

social problems and the legal protection of intellectual property. On the one hand, if a social

sector organization uses the intellectual property laws to protect a process, technology,

invention or creative work essential to its social mission, others will be inhibited from

replicating the same or similar methods of accomplishing positive social change. On the

other hand, the protection of intellectual property can sometimes help social sector

organizations achieve scale and thus accomplish greater social good by, among other things,

generating revenues, minimizing confusion and maintaining quality control.

Every social sector organization should carefully assess and consider the importance of its

intellectual property to the success of its mission in order to select the appropriate level and

method of legal protection for these assets. To assist in this assessment, the following

provides an overview of federal and North Carolina laws protecting copyrights, trademarks,

trade names, trade secrets and patents.

1

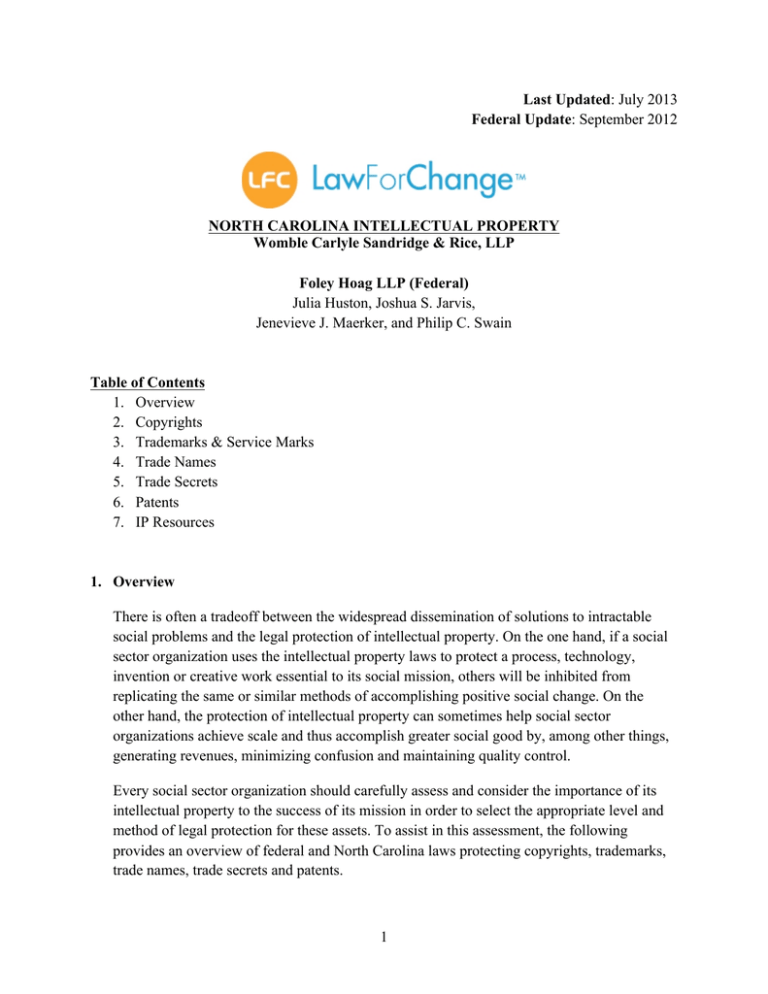

Copyright

Trademark

What it

commonly

protects

Literary and artistic

works; computer

software

Words, phrases,

symbols, logos, and

images associated with

a product or service

When might

this protection

be useful for a

social sector

organization?

1. Ability to license

literary and artistic

works with others

while retaining

ownership

2. Potential source

of revenue

Basic

Requirements

1. Work must be

original and

creative

2. Work must be

shown in a tangible

medium of

expression

1. Prevent others from

using your

product/service name

and causing confusion

2. Increase awareness

by consistently using

same brand names and

slogans

3. Help create a brand

1. Must act as an

identifier of source

2. Must be distinctive

3. Must not infringe any

existing trademark

rights

Patent

New and useful inventions

and processes

Trade Secret

Information that is

not generally known

1. Potential source of

revenue

2. Ability to license

inventions and technology

with others while retaining

ownership

1. Protect donor lists

and strategic plans

for fundraising

2. Protect formulas

and business

information or knowhow

1. Novelty – invention

cannot be "anticipated" or be

identical to a previous

invention

2. Non-Obviousness invention must be different

enough from previous

inventions so it is not

obvious to a person skilled

in the art

3. Utility - invention must

have a useful purpose.

Yes

1. Owner of the

information must

take reasonable

measures to maintain

secrecy

2. The information

must have some

value to the

organization

Is federal

protection

available?

Yes

Yes

Is state

protection

available?

No

Often, but not in every

state.

No

Yes

Not necessarily, but

it is advisable. A

work is protected as

soon as it is created,

but one must

register before suing

for infringement

Once a work is

created or

published, owner

can use © to

indicate copyright

claim. Not

necessary to file

before using this

symbol.

Not necessarily, but it is

advisable. Federal

registration is

presumptive evidence

of ownership and

validity of mark.

Yes

No

Necessary to

file with the

government to

receive

protection?

Symbols to

indicate claim

of right

If trademark is

unregistered or in the

process of registration:

After filing you can use:

“patent pending” to warn

others that you claim the

TM

right.

If trademark is federally “Patented” or “pat.” along

registered: ®

with the patent number

should be marked on the

product after the patent

issues.

2

Limited

There is no symbol to

indicate ownership of

a trade secret.

2. Copyrights

Copyrights are governed exclusively by federal law (17 U.S.C. § 101, et seq.). “Copyright”

refers to the rights an “author” obtains by creating original “works of authorship” such as

literary, musical, dramatic, and artistic works, and computer programs. A copyright enables

an author to protect his or her works of authorship from unauthorized use (copying,

distribution, performance, and display of the work and creation of translations and other

derivative works). Anyone who without authority exercises a right reserved exclusively to

the copyright owner is considered to infringe the copyright and may be liable for actual

damages (plaintiff's actual losses plus any profits of the infringer that were not taken into

account in calculating the plaintiff’s losses) or statutory damages (damage amounts provided

by the copyright statute) and may be subject to an injunction.

Copyright law distinguishes between an idea and an expression of an idea. Only the

expression is protected. Thus, copyright law does not protect ideas, procedures, processes,

systems, methods of operation, concepts, principles or discoveries revealed by copyrighted

works.

To be eligible for copyright protection, all works must meet two basic requirements. First,

the work must be fixed in a copy or some other tangible form, e.g., book, audio CD,

photograph. Second, the work must be the result of original, creative, and independent

authorship.

Under limited circumstances, a copyright-protected work may be used without permission if

the use is considered “fair use.” Four factors, laid out in 17 U.S.C. § 107, are considered in

determining whether a particular use is a fair use: 1) the purpose and character of the use,

including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational

purposes; 2) the nature of the copyrighted work; 3) the amount and substantiality of the

portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and 4) the effect of the use upon

the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The difference between fair use and infringement is often difficult to determine. Generally,

using only a small portion of a work, for purposes of news reporting, parody, education,

scholarship, criticism, or commentary in a way that will not affect the value of the

copyrighted work may be considered fair use.

a. Copyright Registration

No publication, or registration in the Copyright Office, is required to secure copyright

protection. Copyright is secured automatically when the work is created, and a work is

“created” when it is fixed in a tangible medium for the first time. It is nevertheless

3

advisable to register a copyright with the Copyright Office. Registration provides

evidence of the owner’s title to the work and is a prerequisite to bringing a lawsuit for

copyright infringement. In addition, early registration (that is, registration that pre-dates

the alleged act of infringement) entitles the owner to seek statutory damages and

attorney’s fees. Because actual damages may be difficult to prove, the threat of statutory

damages adds strength to a claim for copyright infringement and may result in quick and

inexpensive resolution of the case. Registration can also provide actual notice of

copyright ownership and can therefore assist responsible content users in avoiding

inadvertent infringement.

The owner of copyright in a U.S. work must register or pre-register the copyright prior to

initiating a lawsuit for infringement. Federal copyright registration requires that a

copyright application be filed with the U.S. Copyright Office. There are three ways an

application may be submitted to the U.S. Copyright Office: (1) registration online; (2)

registration with a printable, fill-in form appropriate to the type of work (e.g., literary,

visual art, sound recording, etc.; these forms are processed more quickly than paper

forms); and (3) registration with paper forms. More information about these forms is

available at http://www.copyright.gov/eco. The fee for filing a copyright application is

$35 if it is submitted online. The fee for the two other methods discussed above is $65.

In addition to the application and fee, an applicant for copyright registration must submit

a complete, non-returnable copy of the work being registered (or acceptable identifying

information for certain types of works, such as unpublished fine art). For most published

textual works, the deposit requirement is two copies of the best edition. Because the

deposit is public information, registration of copyright in a work is generally inconsistent

with maintaining the work or its content as a trade secret. Note, however, that there are

special rules for depositing computer software, which may enable the copyright

owner to register copyright while continuing trade secret protection.

Registration may be made at any time within the life of the copyright. A copyright

registration is effective on the date the U.S. Copyright Office receives all required

application items notwithstanding how long it takes to process the application.

b. Copyright Notice

It is advisable but not required for copyright owners to affix a copyright notice to each

copy of their work. The copyright notice consists of three elements: the word

“copyright”, “copr.” or the copyright symbol “©”; the year of first publication; and the

copyright owner’s name. Notice can prevent inadvertent infringement and prevent an

infringer from mitigating damages by claiming innocent infringement.

c. Work Made For Hire

4

In most cases, the person who creates a work is presumed to be the owner of the work

and to hold copyright in the work; however, there is an exception when a work is “made

for hire.” A “work made for hire” arises in two situations. The first is in an employeremployee relationship. A work created by an employee within the scope of his or her

employment is considered a “work made for hire” and ownership of the work vests in the

employer. The employer may be a firm, an organization, or an individual. The second

situation in which a “work for hire” may be created is when all three of the following

conditions are met: 1) a work is specially ordered or commissioned, 2) the work falls into

one of the nine categories listed in the statute, 17 U.S.C. § 101 (e.g. a contribution to a

collective work, part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, a translation, etc.),

and 3) the parties have a signed written agreement stating that the work will be

considered a “work made for hire.”

Note that independent contractors “hired” to create a copyrightable work are not

“employees” for purposes of copyright law. Therefore, it is absolutely imperative that a

company engaging an independent contractor enter into a contract stating precisely who

will own the rights to the work. If the company is intended to be the owner, the parties

must set forth the assignment in writing. It is worth noting that the definition of

“employee” is not as clear cut as it might seem. So, regardless of whether the author is an

employee or an independent contractor, a written agreement is usually advisable to

clarify expectations between the parties and, where applicable, to vest ownership in the

company. For more information, please see “Works Made for Hire under the 1976

Copyright Act,” published by the United States Copyright Office.

d. Duration of Copyright Protection

Copyright protection remains vested in the author for the duration of the copyright unless

transferred by written assignment. The duration of copyright protection depends upon the

identity of the author or authors, when the work was created and when the federal

copyright protection was first obtained. Generally, for works created on or after

January 1, 1978, the following terms apply:

•

•

•

A work of an individual author is protected for the life of the author plus 70 years.

Joint works prepared by two or more authors are protected for the life of the last

surviving author plus 70 years.

Anonymous works, pseudonymous works and works made for hire are protected

for 95 years from the date of publication or 120 years from the date of creation,

whichever is shorter.

Additional information about copyrights and the registration process can be found at

http://www.copyright.gov.

5

3. Trademarks and Service Marks

A trademark may be any word, name, symbol, design or device or any combination thereof

used by a party to identify its goods or services and to distinguish them from those of other

providers. Trademarks and service marks are essentially identical, except that trademarks are

used to identify the source of goods sold, and service marks are used to identify the source of

services offered. Ownership of a mark begins when it is used in commerce in connection

with goods and services so that consumers begin to associate or identify it with a particular

source. Trademarks need not be registered with the United States Patent and Trademark

Office in order to be protected. A trademark may be protected under the common law or state

law. The benefits of registration will be discussed below.

a. Selection of a Trademark

The selection of a trademark should be carefully considered. The level of protection

against infringement of a trademark varies with the strength and uniqueness of the mark.

Arbitrary or fanciful marks are the strongest type of marks because they bear no logical

relationship to the underlying product. Often they consist of a coined name that has no

dictionary definition. For example, “Texaco” for gas stations, “Apple” for computers,

and “Kodak” for film and cameras are arbitrary or fanciful marks.

Suggestive marks are weaker than arbitrary or fanciful marks because they convey

information about the ingredients, qualities or characteristic of the goods or services

provided. Examples of marks held to be suggestive are “Citibank” for banking services,

“Chicken of the Sea” for tuna, and “7-Eleven” for convenience stores.

Descriptive marks are weaker and less defensible than suggestive marks. A descriptive

trademark is a name that describes some characteristic, function, or quality of the goods.

For example, “Holiday Inn” for hotels, “All Bran” for bran cereal and “Chap Stick” for

lip balm are all examples of descriptive marks. Descriptive marks are not entitled to

trademark protection without showing that the public associates the term with a particular

provider of services, rather than just the services in general.

Generic “trademarks” are not trademarks at all and are not enforceable. Generic marks

actually denote the product itself. (i.e. “Visiting Nurses” for a visiting nurse service.) An

otherwise valid trademark can become generic if the consuming public continuously

misuses a trademark to identify a generic class of products. For example, the terms

“aspirin,” “cellophane,” and “Murphy bed” are all former trademarks that have become

generic through public use as generic terms. Genericism is a valid defense to a trademark

infringement claim.

6

Selection of a mark should be accompanied by a trademark search to determine whether

someone else has already adopted or used a mark that is the same or similar to the one

desired. Publications, both hardcopy and on-line, provide lists of existing trademarks,

registered and unregistered, and there are businesses that specialize in trademark

searches. These search resources are identified in the Resources section below.

Actual and potential trademark conflicts should be avoided, in order to avoid the

possibility of an expensive infringement lawsuit. Of even greater concern is the potential

loss of the right to use a mark after considerable expenditures in marketing and

advertising using the mark.

b. Advantages of Trademark Registration

The principal method of establishing rights in a trademark is actual use of the mark. In

the U.S. (but not in most other countries), both federal and state law provides for the

protection of unregistered “common law” trademarks. An individual or entity claiming

common law trademark rights in a term may wish to use the “” symbol. Use of this

symbol effectively alerts others to the user’s claim of trademark rights in the term.

Despite protection of common law trademark rights in the United States, registration of a

trademark under federal and/or state law can be extremely useful.

Federal registration of a mark is presumptive evidence of the ownership of the trademark

and of the registrant’s exclusive right to use the mark in interstate commerce, thus

strengthening the registrant’s ability to prevail in any infringement action. It also

provides public notice of the registrant’s claim of ownership as well as listing in the U.S.

Patent and Trademark Office database, which could deter the adoption and/or registration

of potentially infringing marks.

Federal registrations may also be recorded with the U.S. Customs and Border Protection

Service, which can aid registrants in preventing the importation into the U.S. of foreign

goods that bear an infringing trademark. There are also less tangible advantages of

registration, such as the goodwill arising out of the implied government approval of the

trademark.

While the advantages of state registration are not as extensive as federal registration,

there may be some cases where it is advisable. For example, in situations where sales or

services will occur only within a particular state, it would make sense to register at the

state level.

c. Federal Registration Process

7

Federal trademark registration requires that a trademark application be filed with the U.S.

Patent and Trademark Office. For a step-by-step description of the trademark selection

and registration process, see http://www.uspto.gov/web/trademarks/workflow/start.htm.

A federal application may be based on actual use of the mark, or on the applicant’s intent

to use the mark in the future. In general, the application must identify the mark and the

goods/services with which the mark is used or is proposed to be used, the date of the first

use, and the manner in which it is used. The application must be accompanied by

payment of the requisite fee, a drawing page depicting the mark, and, for a use-based

application, a specimen of the mark as it is actually used. The fee for filing depends on a

variety of factors but begins at $280 per class. A current list of trademark fees is

available at http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/qs/ope/fees.htm.

After the application is filed, it is reviewed by an examiner who evaluates among other

matters, the substantive ability of the mark to serve as a valid source identifier and the

possibility of confusion with existing marks. The examiner may ask questions to clarify

various aspects of the application. The applicant must timely respond to any questions.

Additionally, the examiner may reject the application and the applicant may respond with

reasons why the examiner should reconsider. If the examiner makes a final rejection of

the application, the examiner’s decision can be appealed to the Trademark Trial and

Appeals Board. An adverse decision by that body can be appealed to federal court.

If the application is approved, the mark is published in an official publication of the

Patent and Trademark Office (http://www.uspto.gov/web/trademarks/tmog/). Opponents

of the registration have thirty days after publication, or such additional time as may be

granted, to challenge the registration. If no opposition is raised, or if the opponent’s

claims are rejected, an applicant whose mark is already in use receives a “certificate of

registration.”

An applicant whose trademark is proposed for registration before actual use receives,

upon approval of the application, a “notice of allowance.” An applicant who receives a

notice of allowance must within six months of receipt of the notice furnish evidence of

the actual use of the trademark or file an extension, which will give the applicant another

six months to claim actual use. Up to five extensions may be filed. Once the applicant has

provided evidence of actual use, the applicant is then entitled to a certificate of

registration. Failure to furnish evidence of the actual use of the mark within the time

allowed results in rejection of the application.

An applicant using an unregistered mark should consider adding a trademark notice to its

mark consisting of “.” This notice will alert others that the user is asserting trademark

rights in the mark. Once the mark has achieved federal registration, the symbol “”

8

should be used. (The symbol “” cannot be used with common law or state-registered

marks.)

d. Post-Certificate Federal Procedure

A certificate of trademark registration, issued by the Patent and Trademark Office,

remains in effect for ten years. However, by the end of the sixth year after the date of

registration, the owner must file an “affidavit of use,” attesting to the fact that the mark is

still in use, and pay an additional fee to keep the registration alive. The owner must make

the same filing by the end of the tenth year after registration to renew the mark for an

additional ten-year term. The window during which both of these filings must be made

for the trademark to avoid cancellation is one year prior to the filing due date or during a

6-month grace period immediately after the filing due date. For example, if a trademark

was registered on January 1, 2009, the owner could file the 6-year filing between January

1, 2014 and June 30, 2015 and the 10-year filing between January 1, 2018 and June 30,

2019.

After at least five years of continuous use of a trademark following receipt of a certificate

of registration, a registrant can seek to have the status of the mark declared

“incontestable.” This elevates the registration from “presumptive” evidence of the

registrant’s exclusive right to use of the mark to virtually conclusive evidence of

exclusive right. To do so, the registrant must furnish the Patent and Trademark Office

with a declaration attesting to continuous use of the mark for at least five years.

Additionally, there must not be any outstanding lawsuit or claim that challenges the

registrant’s right to use the mark.

e. State Law & State Registration Process

State trademark registration is typically less expensive and faster than federal registration.

It is also typically easier. At the federal level, each application is scrutinized by an

examining attorney for deficiencies and conflicts with other marks. Most states do not

have the resources to provide such a rigorous examination process. While the state

registration process offers certain advantages, the protections provided are relatively

limited in comparison to federal registration. State registration generally only protects a

mark in that state. Therefore, if an organization is operating solely within one state, state

trademark registration may be a useful alternative to federal registration. Also state

registration can help establish notice, meaning that others should be on notice that the

protected mark is in use.

Registered trademarks in North Carolina are protected through the North Carolina

General Statutes (“N.C.G.S.”) Chapter 80 Trademarks, Brands, etc. To register a mark,

the applicant must submit a trademark application that may be found on the state’s

9

website along with a fee to the Secretary of State. The fees start at $75 for a new

registration. The application may be found on the state’s website at:

http://www.secretary.state.nc.us/trademrk/.

After five years, a registrant must submit a form to the Secretary of State proving that the

use of the mark is within the standards set by North Carolina. Registrations are effective

for a period of ten years, and may be renewed in successive ten year terms by submission

of a form provided by the Secretary of State within 6 months of the expiration of the term

of registration. The renewal fee is $35.

f. Enforcement

Once a trademark is registered, some form of enforcement against infringers usually is

necessary because protection can be lost through acquiescence or longstanding

inattention. One protection strategy is to appoint a person or persons to monitor the

trademark registers (federal and state) and the Internet and to attend industry trade shows

to discover any infringing marks. In addition, periodic searches of similar marks can be

made, much like the search conducted when seeking to register or use a new name or

mark. The same search companies have “watch” services that they will perform for

trademark owners. (See Resources section below.)

If the owner of a mark identifies a potential infringer, the owner should carefully research

the nature and scope of the potential infringement. Not only could the potential

infringer’s use pre-date the owner’s own use (and possibly create rights superior to the

owner’s rights), but the use also may be distinct enough in terms of trade, market area, or

geography to preclude infringement. The ultimate test, made up of several factors, is

whether there is a likelihood of confusion between the two marks at issue.

If litigation does become necessary, the owner of the mark may have the following

remedies available to it: (1) an injunction against threatened or actual infringement; (2)

damages for lost profits and lost reputation or goodwill; (3) enhanced damages if the

infringer’s conduct was willful and malicious; and (4) costs and reasonable attorneys’

fees under exceptional circumstances. It is also possible to challenge federal applications

in the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office apart from an infringement action, the sole

remedy of which is the refusal of such applications.

Additional information about trademarks and the registration process can be found at

http://www.uspto.gov.

4. Trade Names

A trade name is distinguishable from a trademark in that a trade name may identify not only

goods and services, but also the business of and/or goodwill of an organization as a whole.

10

To the extent a trade name is also used as a trademark, it can be registered and protected as a

trademark at the federal and state levels.

Trade names are otherwise governed by state law and not covered by federal statutes.

Under state law, trade names are sometimes referred to as “DBAs” (doing business as) or

“fictitious business names.” Persons conducting business under a “fictitious business name”

typically must make one or more filings with the state and/or city in which they are doing

business.

a. North Carolina Filing Requirements

North Carolina protects trade names under the title of “doing business as.” N.C.G.S.

Chapters 66-68 require that before starting a business in North Carolina, the name must

be registered with the Secretary of State. A certificate must be presented that conveys the

name of the business and the names and addresses of the owners. Business names are

indexed in the registers of deeds across the state.

5. Trade Secrets

In disputes between private parties, the protection of trade secrets is largely a distinctly statecontrolled area. Trade secret protection can be of potentially infinite duration; it exists for as

long as the secrecy of the trade secret is maintained. State law varies as to whether a trade

secret owner is required to make continuous use of a trade secret in order to receive

protection. As detailed below, federal law provides criminal and civil penalties for

misappropriation of trade secrets in appropriate circumstances.

a. Definition of a Trade Secret

Many states (not including North Carolina) have adopted some variation of the Uniform

Trade Secrets Act, which protects information that (1) derives economic value from not

being known to the public and (2) is the subject of reasonable efforts to maintain its

secrecy. A trade secret can include a business formula, compilation, pattern, program,

device, method, technique, or process which, though neither copyrighted nor patented, is

used in the conduct of the owner’s business, is not disclosed to the public, and provides

the owner with some competitive advantage.

The following factors will likely be considered in determining whether a trade secret

exists:

•

•

The extent to which the information is known outside the owner’s organization;

The extent to which it is known by employees and others involved in the

organization;

11

•

•

•

•

The extent of measures taken by the owner to guard the secrecy of the information

(e.g., labeling the information “Trade Secret” or “Confidential,” advising

employees of the existence of a trade secret, limiting access to the information

within the company on a “need-to-know basis,” and controlling access to

company premises);

The economic value of the information to the owner and the owner’s competitors;

The amount of effort or money expended by the owner in developing the

information; and

The ease or difficulty with which the information could be independently

acquired or duplicated by others.

No one factor is dispositive. Some information does not qualify for trade secret

protection, including publicly available information, general industry skills and

knowledge, and abstract goals or ideas.

b. Misappropriation of Trade Secrets

Misappropriation of a trade secret occurs when a person acquires the trade secret of

another by means which the person knows or has reason to know constitute improper

means, or when a person discloses or uses the trade secret without the express or implied

consent of the trade secret owner.

The Uniform Trade Secrets Act provides for injunctive relief if a trade secret is

misappropriated or there is a threat that a trade secret will be misappropriated. The

Uniform Trade Secrets Act also provides for awards of monetary damages, covering both

actual loss and unjust enrichment caused by the misappropriation. Absent proof of actual

loss or unjust enrichment, a reasonable royalty may be awarded. If the misappropriation

is “willful and malicious,” the court may award punitive damages of up to twice the

above-mentioned damages and attorneys’ fees. If a misappropriation claim is made in

bad faith, a court may award attorneys’ fees to the accused misappropriator.

Pursuant to the Uniform Trade Secrets Act, misappropriation is not limited to the initial

act of improperly acquiring trade secrets. The use and continuing use of the trade secrets

is also misappropriation. It is also noteworthy that the Uniform Trade Secrets Act does

not require that the defendant gain any advantage from disclosure of a trade secret in

order for misappropriation to occur. It is sufficient to show disclosure of the trade secret

with actual or constructive knowledge that the secret was learned under circumstances

giving rise to a duty to maintain its secrecy.

It is important for organizations to take significant steps to keep sensitive information

secret; an organization may not claim misappropriation of a trade secret if there was no

effort taken to treat the information as secret. Some practical means by which a company

12

can help avoid misappropriation of its secrets include reminding employees about

confidential communications, asking employees to sign confidentiality agreements, and

marking sensitive communications with the word “secret” or “confidential.” A trade

secret owner can defeat its own rights by disclosing the trade secret without a

confidentiality obligation, losing knowledgeable employees without a confidentiality

obligation or non-compete agreement, lax security, or applying for a patent and allowing

the application to publish but not receiving the patent.

In some states and under the federal laws described below, one may also be criminally

liable for the intentional misappropriation of a trade secret.

Under the Uniform Trade Secrets Act, an action for misappropriation must be brought

within three years after the misappropriation is, or reasonably should have been,

discovered. The statute of limitations may vary by state.

A trade secret is not protected against discovery by fair and honest means, such as

independent invention or reverse engineering.

As a general principle, the more difficult the information is to obtain and the more time

and resources expended by the employer in gathering it, the more likely it is that a court

will find such information to be a “trade secret” under the Uniform Trade Secrets Act.

c. Protect Yourself Against Accusations of Misappropriation

Savvy companies take steps to proactively protect themselves from claims of trade secret

misappropriation. Such steps can include:

•

•

•

•

•

Screening incoming employees for confidentiality obligations;

Responding (internally and externally) to cautionary letters from the former

employer of a new employee;

Researching state law concerning enforceability of non-compete agreements

before hiring;

Keeping documentation of the company’s scientific knowledge and independent

development; and

Limiting the amount of third-party information that the company agrees to keep

confidential.

Companies should think ahead about how they acquire information, who owns the

information, and what duties they have to the information’s owners.

d. Federal Trade Secrets Law

13

Two federal laws may help protect against misappropriation of trade secrets: the

Economic Espionage Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1831-39, and the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act,

18 U.S.C. § 1030.

The Economic Espionage Act (EEA) makes it a federal crime to misappropriate trade

secrets and provides protection against both domestic and foreign conduct. The EEA

criminalizes misappropriation of trade secrets in two main areas based upon who benefits

from the conduct. Section 1831 criminalizes conduct that will benefit a foreign

government, foreign entity, or agent of either. Section 1832 criminalizes trade secret

misappropriation for the economic benefit of anyone other than the owner, provided the

misappropriation is related to a product placed in interstate or international commerce.

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) provides another federal means for

protecting trade secret rights by criminalizing certain activity where a computer is used.

As it can be applied to trade secret information, the CFAA makes it a crime to

intentionally access a computer without authorization or exceed authorized access and

obtain information from any protected computer (a computer used in interstate or foreign

commerce or communication). The CFAA also makes it a crime to intentionally access a

protected computer without authorization and cause damage or loss. Since computers are

used everywhere in business today, with a substantial number connected to the Internet,

the CFAA covers most computers. Notably, the CFAA places no restriction on what

constitutes “information.” Therefore, the sometimes difficult issue of proving the

existence of a trade secret does not arise. Damage includes any impairment to the

integrity of information, and this has been interpreted to include conduct that

compromises the secret nature of information.

e. North Carolina Trade Secrets Law

N.C.G.S. Chapter 66 Article 24 is the Trade Secrets Protection Act. North Carolina

protects trade secrets by allowing courts to stop misappropriation through a court order.

Courts are generally required to preserve the secrecy of trade secrets. To prove

misappropriation, one must show that a person 1) knew or should have known that the

information was a trade secret, and 2) “had a specific opportunity to acquire it for

disclosure or use or has acquired, disclosed, or used it without the express or implied

consent or authority of the owner.”

6. Patent Protection

A patent is an intellectual property right granted by the United States government to an

inventor. In exchange for public disclosure of the invention, the U.S. government conveys to

the inventor certain property rights concerning the invention for a limited time period. The

property rights include the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing

14

the invention. Patent rights are not affirmative rights to make, use, sell, and import their

inventions, but rather the right to exclude all others from doing so. A valid patent forecloses

use of the patented invention by any other party, even if another party independently

conceives of the identical invention.

a. United States Patents

Patents are governed exclusively by Federal law (Title 35, U.S.C.), although any

agreement to license a particular patented invention is a contract and will be governed by

state law. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is the federal agency

that promulgates rules, grants patents and through which filing and prosecution of patent

applications occurs. Patent rights conveyed by the USPTO are only enforceable within

the borders of the United States; therefore, a patent owner may consider filing foreign

patent applications if patent protection outside the United States is desired. Other

countries have similar processes and an inventor can obtain similar rights in other

countries.

b. Foreign Patents

Patents are generally applied for on a country by country basis. Under the Paris

Convention, which has been signed by almost every industrialized country, a foreign

patent application corresponding to a United States patent application will be treated as if

it were filed on the same day as the United States application, so long as the foreign

counterpart is filed within one year.

There are several options for filing a foreign patent application, including filing the

foreign application directly with the patent office of the country in which protection is

desired, or filing through a regional patent office (such as the European Patent Office,

which can issue a bundle of patents that can be enforced in any member country that is

designated in the filing). Another option is filing through the Patent Cooperation Treaty

(PCT), which came into force in 1978. The PCT is the international treaty allowing an

inventor to file a single international application. This application may be used

subsequently to obtain a national patent in one or more countries as long as they are

members to the treaty. As of 2012, 146 countries adhere to the treaty, including the

United States. To find out more consult World Intellectual Property Organization

(WIPO) website: http://www.wipo.int/.

c. Types of Patents

There are three types of patents issued by the United States Patent Office: utility, design,

and plant. Although the procedures for each are similar, each type has specific

requirements. For example, both plant and design patents are limited to one claim,

whereas, utility patents may have an unlimited number of claims.

15

i.

Utility patents include patents granted for inventions relating to any useful and

new process, article of manufacture, machine, or composition of matter, or

any useful and new improvement thereof. It generally governs the functional

aspects of a machine, manufacturing process, article made, method of use, or

composition of matter. The term of protection for a utility patent is 20 years

from the date the patent application is filed.

ii.

Design patents cover ornamental features of a manufactured item and may be

granted to any person who creates a new, non-obvious, original, and

ornamental design for an article of manufacture. This is separate and distinct

from the functioning parts and features of a manufactured item, which would

instead be covered by a utility patent. Design patents contain only one claim,

which itself describes the ornamental design or appearance of an article. The

term of protection for a design patent is 14 years from the grant date. The

numbers of all design patents begin with “D” to designate them as design

patents.

iii.

Plant patents encompass asexually reproducing plants and may be conveyed to

any person who invents or discovers and reproduces asexually a new and

distinct type of plant. (Sexually reproduced varieties are also entitled to

certain legal protection upon certification, pursuant to the Plant Variety

Protection Act of 1970.) Plant patents have only one claim and their term is

20 years from the date of filing.

d. Who can file for a patent

Any natural person who invents a machine, composition of matter, a process, an article of

manufacture or an improvement thereof can file a patent application. The person filing

must be the inventor, with certain specific exceptions. Corporations are not natural

persons; therefore, they cannot file for an invention, even if it was created by an

employee.

e. Patent Professionals

To obtain a patent an inventor may file and prosecute his own application, pro se, or be

represented by a registered patent professional. Registered patent professionals who are

attorneys are referred to as patent attorneys, while registered patent professionals who are

not attorneys are referred to as patent agents. The United States Patent Office maintains a

listing of registered patent professionals (https://oedci.uspto.gov/OEDCI/). No person

other than a registered patent professional may represent an inventor before the USPTO.

To become a registered patent professional one must have a requisite amount of scientific

or engineering education and pass a USPTO-administered examination. The reasoning is

that to effectively establish and protect an inventor’s property rights the professional must

16

have a sound knowledge of science or engineering (and have a minimum level of skill in

patent law). Importantly, a patent professional who is not a lawyer cannot represent an

inventor in other legal matters even regarding the patented invention. For example, a

patent agent (a patent professional who is not an attorney) may not represent an inventor

during licensing negotiations, license drafting and/or any litigation even if it involves the

same patented invention.

f. Ownership of the Patent (and/or Patent Application)

In general, an inventor owns all rights to a patent application on which they are listed as

an inventor as well as to any resulting patents which issue from the patent application.

Patent rights are freely alienable and therefore patent rights may be sold, purchased, or

licensed as if they were any other property right. An assignment (sale) of a patent

transfers all rights, title and interest in the patent for the full life of the patent to the

assignee (new owner). This means that the assignee has the right to exclude all others

from making, using, importing, or offering to sell the patented invention. Patent

applications may also be assigned.

With respect to inventions made by an employee, the employer may claim ownership in

the invention, depending on the circumstances of its conception and development, the

employment agreement and whether the invention was within the scope of the

employee’s employment. To avoid any uncertainty, however, employees should be

required to sign an employment agreement that includes a covenant to assign all

inventions to the employer and/or a prospective assignment of any and all inventions

which are made within the scope of employment. Usually, this covenant and/or

prospective assignment will result in the employer being the sole owner of the patent.

g. Patentability

i.

Subject Matter

Patentable subject matter is specified in 35 USC § 101. According to the statute,

patents may be granted to anyone who “invents or discovers any new and useful

process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful

improvement thereof.” The United States Supreme Court has stated further that

Congress intended patentable subject matter to include “anything under the sun

that is made by man.” Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303 (1980).

However, certain things are not patentable such as laws of nature (laws of

relativity or gravity), things that occur naturally, and ideas or suggestions.

Patent law has been developed to reward the invention of new machines,

processes, and compositions of matter, not just the idea or suggestion of one.

17

Patentable subject matter includes new and useful machines, compositions of

matter and processes. Machines include, for example, a flat screen TV or a copy

machine. Compositions of matter may be a new drug or a new type of plastic.

Processes include both the method of making something (e.g., a drug, a plastic, or

a baseball bat) and the method of using something (e.g., a drug for the treatment

of asthma or a plastic to make a sturdier window). An improvement falling

within any of these classes may also be patentable. Taken together these

categories of subject matter include practically all things that can be made by man

and the methods for making the products.

One may seek to obtain patent protection on computer software as a “machine,”

“computer program product,” or “process.” Similarly, one may obtain patent

protection on new and non-obvious business methods, particularly if implemented

as a computer-related invention. It should be noted, however, that the question of

what is or is not patentable, particularly with respect to computer software,

business methods, and computer-related inventions in general, is a difficult one

and the standard for what is patentable subject matter has been the subject of

several recent cases in the United States Supreme Court.

ii.

Novelty, Non-obviousness, and Usefulness

The patent law specifies that an invention must be “new” and “useful.” Therefore,

even if an invention fits into one of the appropriate subject matter categories, it

must meet the novelty, non-obviousness, and usefulness requirements. The “new”

prong of the analysis is met if the invention is novel and not obvious. In practice,

determining novelty and non-obviousness can be very challenging and is best

done by patent counsel.

The “useful” prong of the analysis is met if the invention has utility, actually

works, and is not frivolous or immoral. That is, the claimed invention as a whole

must accomplish a practical application; it must have a concrete and tangible

purpose.

h. Determining Patentability

In order to determine novelty and non-obviousness, and hence, patentability of an

invention, it is often useful to search the records of the United States Patent Office,

WIPO and Google Patents. On these websites, one may examine all U.S. patents,

published applications, many foreign patents, and a large number of technical

publications often referred to as “references.” A patent search is customarily performed

by a patent professional. A patent attorney or patent agent may be asked to render an

opinion regarding the patentability of a particular invention. In this way, an inventor can

then make an informed decision as to whether to proceed with the cost of an actual patent

18

application. Note that any reference determined to materially affect patentability must be

disclosed to the USPTO.

i. Patent Application Process

The patenting process can be broken down into two parts: 1) filing the application; and 2)

prosecuting the application.

i. Filing of the application

Patent applications must be filed with the United States Patent Office and may be

filed either as a provisional application or a non-provisional application. Filing a

provisional application is a quick, simple, and cost effective method to officially

file an application with the Patent Office and thereby obtain a filing date

(discussed below). Provisional applications are not examined; instead they act

simply as a place holder for one year. Provisional patent application requirements

are less stringent than those for a regular patent application. The oath or

declaration of the inventor and claims are not required and the application is held

for the 12-month period without examination.

At the end of one year, the provisional application expires, and if a nonprovisional application has not been filed prior to the expiration of the provisional

application, then the filing date of the provisional application is lost. In order not

to “lose” the filing date of a provisional application, when filing a subsequent

non-provisional application an applicant “claims priority” back to the filing date

of the original provisional application. (Note that in order to file a design patent

which claims priority to a non-provisional application, the design patent must be

filed within six months of the filing of the non-provisional application.)

Non-provisional applications are subject to examination by the USPTO. To file a

complete non-provisional patent application one must file a specification,

including at least one claim, an oath or declaration and appropriate fees. The

specification is a description of what the invention is and what it does. The

specification can be filed in a foreign language provided that an English

translation, verified by a certified translator, is filed within a prescribed period.

The oath or declaration can be filed with the specification or within a prescribed

period thereafter. The oath or declaration certifies that the inventor believes

himself or herself to be the first and original inventor. If the inventor does not

understand English, the oath or declaration must be in a language that the inventor

understands. The application must include drawings if drawings are essential to

understanding of the invention. Lastly, the appropriate fees must be included or

paid within a prescribed period. The fees for filing a standard utility application

range from approximately $500 to $1,000 depending upon whether the filing

19

entity is a small or large entity. The fees can increase substantially depending on

number of claims and other specifics.

ii. Prosecution of the application

The process of the application being examined by the United States Patent Office

is called prosecution. After a proper application is filed, the application is

assigned to an examiner with knowledge of the particular subject matter. The

examiner makes a thorough review of the application, reviews the known art in

that subject matter, and the status of existing concepts in the relevant area to

determine whether the invention meets the requirements of patentability. Due to a

backlog of patent application filings, it is not uncommon for the United States

Patent Office to take several years before beginning the examination of a patent

application. Rejection of a patent application by the examiner may be appealed to

the Board of Patent Appeals. Decisions of the Board of Patent Appeals may be

appealed to the federal courts.

Once the examiner has determined that the invention is patentable, and that other

statutory requirements for the issuance of a patent have been met, a patent is

issued on the invention. Patents have a presumption of validity, because they

have (in theory) undergone rigorous analysis as to patentability.

iii. Importance of the filing date

The filing date of a patent application is critical because an Examiner may only

cite during examination that which was in the public domain prior to the filing

date. An application must follow certain mandated rules and procedures to obtain

the filing date. Once an application is filed in the United States, international

treaties allow one year to file corresponding applications in most foreign

countries.

iv. First inventor to file

Until the enactment of the America Invents Act in 2011, the United States

followed a “first to invent” patent system, whereas most foreign countries use

“first to file” system. In first to invent systems, the person to obtain patent rights

is that person who first “invented” (or “conceived”) the machine, composition of

matter, or process. In first to file systems, those who file their patent application

first are granted patent rights, irrespective of whether or not they truly invented

first.

In the event that there was a question as to who invented first (both inventors

having filed patent applications), the USPTO may have declared an interference

20

proceeding to determine the actual first inventor. Generally, the first to conceive

an invention and actually reduce (that invention) to practice (by making the

product or performing the process) or constructively reduce the invention to

practice (by filing a patent application disclosing the invention) would have been

awarded priority in an interference.

The AIA, which was passed and signed into law in 2011, was intended to, among

other things, conform the United States patent laws to international patent laws.

One of its provisions, which will take effect in March, 2013, will change the law

on so that the inventor with the earliest-filed application will be entitled to own

the patent for an invention, over another inventor, regardless of who invented the

claimed subject matter first. As that change comes into effect, the practice of

awarding patents to the first actual inventors through interferences will end.

These changes are intended to begin to harmonize United States patent law with

that of most other industrialized countries.

Unlike most foreign countries, however, the United States first inventor to file

system will not be an absolute novelty system. It will still allow a limited “grace

period” for inventors to file patent applications within one year after publicly

disclosing the invention, without having the disclosure be available as prior art.

v. Loss of Patent Rights

Nevertheless, waiting to file a patent application might very well result in the loss

of all patent rights in the United States and abroad. In the United States, one must

file a patent application within one year of the first public use, disclosure, or

commercial exploitation of an invention. Moreover, any public use, sale, or offer

to sell in the United States, or disclosure anywhere in the world prior to filing a

patent application could bar patenting in foreign countries. The rules regarding

these matters and the deadlines for filing can be very complicated. Patent counsel

should be consulted well in advance of any potential public disclosures.

vi. Maintenance Fees

In most countries, including the United States, periodic maintenance fees are

required to keep a patent in force. For a United States patent, maintenance fees

are due 3 1/2, 7 1/2 and 11 1/2 years from the date of the original patent grant, or

the patent will become abandoned.

j. Patent Marking

After a patent application has been filed, the product made in accordance with the

invention may be marked with the legend “patent pending” or “patent applied for.” After

21

a patent is issued, products should be marked “patented” or “pat.”, together with the U.S.

patent number. If the device cannot be marked, the package or label should be so marked.

It may also be advisable to mark advertisements for the product and product brochures

and inserts.

Although patent marking is not required to obtain an injunction against an infringer, if a

patent owner fails to mark a patented article, the owner cannot recover damages for any

infringement that pre-dated actual notice of infringement. Therefore, marking is critical

in order to maximize recovery of damages.

Before marking an article with a patent number, the patent owner must be certain that the

article being marked is covered by the patent. False marking can result in liability for

damages. Before enactment of the America Invents Act in 2011, damages could be

awarded up to $500 for each article falsely marked. The AIA generally limited damages

for false marking to circumstances where there was competitive injury, although the

United States government can still bring claims for statutory damages of up to $500 for

each article falsely marked.

k. Post-Issuance Matters

i.

Patent litigation

Once a patent is issued, some form of enforcement against infringers may be

necessary. Anyone without authority from the patent holder who makes, uses,

imports, offers to sell, or sells the patented invention in the U.S. during the life of

the patent is considered to “infringe” the patent and may be liable for damages.

Patents can be enforced through infringement actions in the United States federal

district courts. Patent litigation typically takes at least two years from the filing of

a complaint until trial. Patent cases can be and usually are tried to a jury. Many

federal district courts in localities that have a high concentration of patent owners

or are popular patent litigation venues, such as the United States District Courts in

the Northern District of California, the District of Massachusetts, the District of

Delaware, and the Eastern District of Texas, have enacted “local” rules for patent

cases. These rules typically require certain additional disclosures that are

intended to force the parties to disclose their contentions concerning the patent

claims asserted and their defenses, and result in an early ruling by the judge on the

scope of the of the patent claims, which will guide the jury in its deliberations.

Because of the extensive pre-trial proceedings, the need for discovery, and

consultation of technical and economic experts, patent litigation is very expensive

and time-consuming for both plaintiffs and defendants.

Patents (as well as other intellectual property rights, such as trademarks,

copyrights, and trade secrets) can also be enforced through actions seeking

22

injunctions (called exclusion orders) in the United States International Trade

Commission. An exclusion order from the ITC will block infringing products

from being imported into the United States. The International Trade Commission

cannot award damages. However, it has become an increasingly popular venue

for enforcing patents, because it is required by law to complete infringement cases

within 12 to 18 months, and the administrative law judges who handle the

intellectual property cases at the International Trade Commission have developed

a great deal of expertise in patent litigation. Also, unlike in federal district court

litigation, a patent owner can bring a single case against multiple unrelated

infringers in the International Trade Commission.

If it becomes necessary to file a lawsuit against an infringer, the patent owner may

attempt to obtain an injunction against continued infringing activity, as well as

damages. Damages may be based on lost profits caused by the infringing activity

or a reasonable royalty. A patent owner may also be awarded treble damages

(triple the amount of compensatory damages) if the infringer is found to have

willfully infringed. The patent owner may also seek its costs and attorneys’ fees in

exceptional circumstances.

It should be noted that, although issued patents are presumed to be valid, a patent

may be invalidated in a lawsuit if there are grounds to establish that the patent

was somehow wrongfully obtained (e.g., not novel).

Patents may also be challenged and revoked through post-grant proceedings in the

United States Patent Office. These include ex parte reexamination, inter partes

reexamination (which will be phased out as of September 15, 2012), inter partes

review (which will replace inter partes reexamination and become available on

September 16, 2012), and post grant review (which will become available for

patents having a priority date on or after March 16, 2013).

ii. Patent Monetization

a. Licensing

A patent owner is often able to generate revenues by licensing patents to

others. If the owner of a patent is unable to satisfy the needs of the entire

market for the patent, for example, the owner may license the patent to

others to fully exploit the value of the patent. Standard contract law

governs these agreements. One strategy when potential infringers are

identified is to notify the potential infringers and offer them a license in

exchange for royalties.

23

In licensing agreements, the licensor is granting the licensee the right to

make, use, sell, import, and/or offer to sell the patented invention without

any possibility of being sued for that activity which would otherwise be

considered infringing activity. Often times licensing agreements transfer

less than the entire patent rights. For example, a license may be for a

particular development, economic sector, geographic region, or specific

duration which is less than or equal to the life of patent. In addition, some

licenses are “exclusive,” that is, the patent owner promises not to make,

use, sell, import or offer to sell the patented invention and promises not to

license anyone other than the exclusive licensee to do any of the

foregoing; some licenses are “sole,” that is, only the licensee and the

patent owner are permitted to practice the invention.

A social sector organization may decide that in order to advance its social

mission it does not want to maintain exclusive rights to their inventions.

Some social sector organizations would rather make their invention(s)

available to everyone, with the goal of getting the invention into the hands

of as many people as possible who can benefit from it. Other social sector

organizations decide to provide a royalty-free license of their invention to

other social sector organizations and to provide commercial licenses to

businesses in order to raise revenue for their social missions.

b. Patent sales and transfers

In addition to licensing, a patent or a bundle of patents may be sold. In

recent years, a number of new entities have arisen to assist in these

transactions, which have come to be known as patent “licensing

companies” or investment funds; patent “aggregators”; patent “pools”;

patent “brokers”; and patent auctions. These entities may acquire patents

or portfolios of patents, or provide capital to assist in the acquisition of

patents, provide auctions for patents or portfolios of patents, or advise

companies in these transactions.

l. Rights to Patented Inventions

Disputes sometimes arise between employers and employees over the rights to inventions

made by employees during the course of employment. Because of this, employers often

require employees to execute formal agreements under which each signing employee

agrees that all rights to any invention made by the employee during the term of

employment will belong to the employer.

Additional information about patents can be found at http://www.uspto.gov.

24

7.

Intellectual Property Resources

a.

Federal

i. Public Agencies

• U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, http://www.uspto.gov

• U.S. Copyright Office, http://www.copyright.gov

• U.S. Department of Justice, Computer Crime and Intellectual Property

Section, http://www.usdoj.gov/criminal/cybercrime/

• U.S. Federal Trade Commission, www.ftc.gov

• U.S. Customs and Border Protection, http://www.cbp.gov

ii. Private Websites

• Stanford Copyright and Fair Use Center, http://fairuse.stanford.edu/

• World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), http://www.wipo.int/

• Google Patents, http://www.google.com/patents

• Berkman Center for Internet and Society,

http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/metaschool/fisher/domain/tm.htm

iii. Treatises

• McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition

• Nimmer on Copyright

• Chisum on Patents

iv. Trademark Search Services

The following is a sample list of trademark search services. It is not intended

to include all search services, nor is it intended as a recommendation or

endorsement of any of these services.

• Thomson Compumark, http://compumark.thomson.com/do/cache/off/pid/1

• TradeMark Express, http://www.tmexpress.com/services3.php

• Trademark Center, http://tmcenter.com/

• Creative Trademark Services, http://www.creativetrademark.com/

• Allmark Trademark, http://allmarktrademark.com/

b. State

•

North Carolina Secretary of State http://www.secstate.state.nc.us/

25