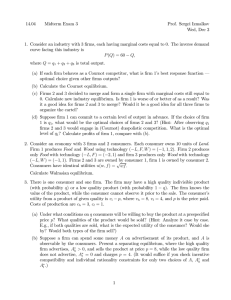

Zenger et al - University at Albany

advertisement