Research report 102: Causes and motivations of hate crime

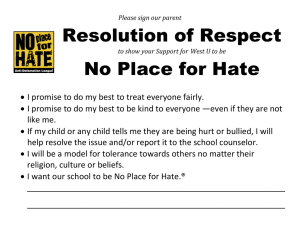

advertisement