FIFO/DIDO Mental Health Research Report 2013

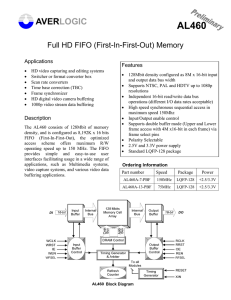

advertisement