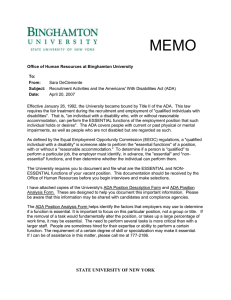

ADA AMENDMENTS ACT OF 2008: Implications

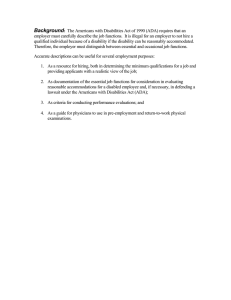

advertisement