For Simulation Use Only i - Bush School of Government and Public

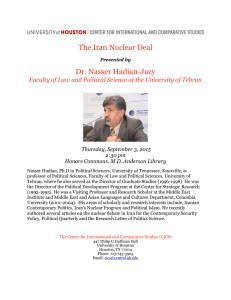

advertisement