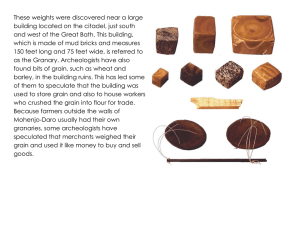

Grain Supply Chain Study

advertisement