ECTS – European Credit Transfer and Accumulation system:

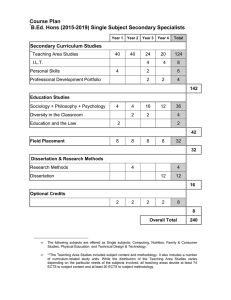

advertisement