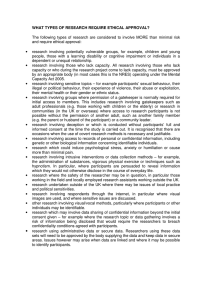

Ethical guidelines - Social Research Association

advertisement