Immigration and the Czech Republic (with Special Respect to the

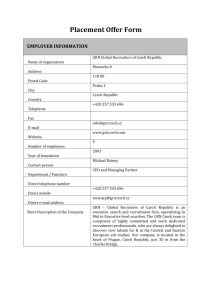

advertisement