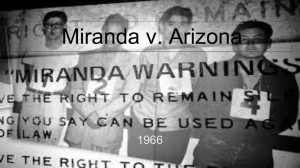

The Impact of Miranda Revisited

advertisement