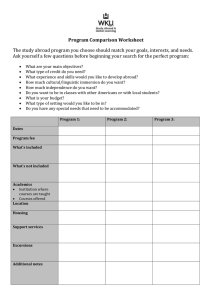

emerging technologies integrating technology into study abroad

advertisement