HEP Overview

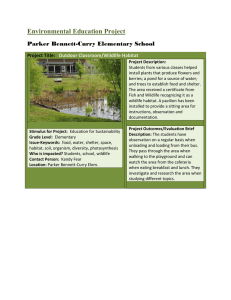

advertisement