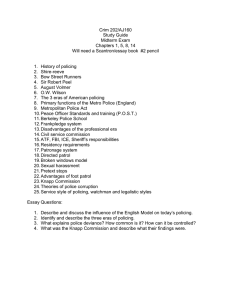

Guidelines on Charging for Police Services

advertisement