"Inside-Out" Manual: Conducting Construction

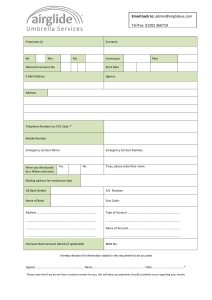

advertisement