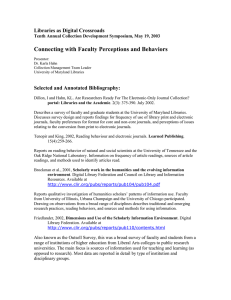

Do We Still Need Books? A Selected Annotated Bibliography

advertisement