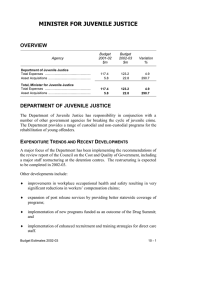

report - ohchr

advertisement