April 2014 - Park University

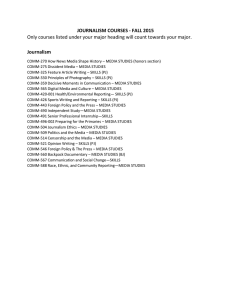

advertisement