SUBVERSION OF TRADITIONAL FRANCOIST HISTORIOGRAPHY

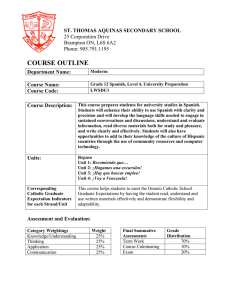

advertisement