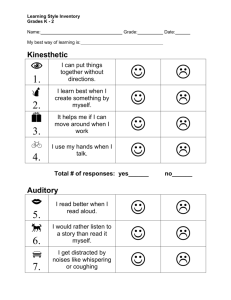

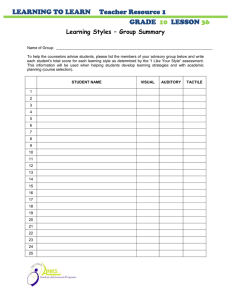

Using Technology in an ESL Course to Accommodate Visual

advertisement