Obstructive Sleep Apnea–Hypopnea and Related Clinical Features

advertisement

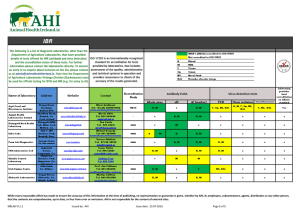

Obstructive Sleep Apnea–Hypopnea and Related Clinical Features in a Population-based Sample of Subjects Aged 30 to 70 Yr JOAQUIN DURÁN, SANTIAGO ESNAOLA, RAMÓN RUBIO, and ÁNGELES IZTUETA Sleep Unit, Service of Pneumology, Hospital Txagorritxu, Servicio Vasco de Salud—Osakidetza, José Achótegui s/n, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain; Research Unit, Department of Health, Basque Government, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain; and Basque Institute of Statistics, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain The prevalence and related clinical features of obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea (OSAH) in the general population were estimated in a two-phase cross-sectional study. The first phase, completed by 2,148 subjects (76.9%), included a home survey, blood pressure, and a portable respiratory recording, whereas in the second, subjects with suspected OSAH (n ⫽ 442) and a subgroup of those with normal results (n ⫽ 305) were invited to undergo polysomnography (555 accepted). Habitual snoring was found in 35% of the population and breathing pauses in 6%. Both features occurred more frequently in men, showed a trend to increase with age, and were significantly associated with OSAH. Daytime hypersomnolence occurred in 18% of the subjects and was not associated with OSAH. An apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) ⭓ 10 was found in 19% of men and 15% of women. The prevalence of OSAH (AHI ⭓ 5) increased with age in both sexes, with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.2 for each 10-yr increase. AHI was associated with hypertension after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, neck circumference, alcohol use, and smoking habit. This study adds evidence for a link between OSAH and hypertension. Underdiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea (OSAH) (1, 2) represents a major public health burden (3–9) and further data on the natural and pathophysiological importance of untreated OSAH or accompanying symptoms, particularly daytime hypersomnolence and functional impairment (OSAH syndrome) (10–12), are essential to rational clinical decisions about whom to treat. Epidemiological investigation of OSAH has been hampered by difficulties in obtaining valid data from adequate population-based samples whose diagnosis is based on a full sleep study (polysomnography). Moreover, differences in defining cutoff points for the apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) has contributed to variability in case finding and prevalence estimates of OSAH and OSAH syndrome (13, 14). We estimated the prevalence of OSAH among a representative sample of the general population of men and women 30 to 70 yr old from Vitoria-Gasteiz, Basque Country (Spain), and investigated the spectrum of clinical features including hypertension associated with sleep-disordered breathing. METHODS Sample Noninstitutionalized people aged 30–70 yr who were residents of Vitoria-Gasteiz (206,116 white population, 20% of people over 65 yr of age, life expectancy at birth 75 yr for men and 83 yr for women), Basque (Received in original form May 17, 2000 and in revised form November 17, 2000) This study was supported by grants from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS 93/0553 and 95/1176) of the Ministry of Health, Department of Health, Basque Government (1992 and 1995), Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) (1996), and Caja Vital-Kutxa (1994). Correspondence and requests for reprints should be addressed to Dr. Joaquin Durán, Sleep Unit, Service of Pneumology, Hospital Txagorritxu, Servicio Vasco de Salud—Osakidetza, José Achótegui s/n, E-01009 Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain. Am J Respir Crit Care Med Vol 163. pp 685–689, 2001 Internet address: www.atsjournals.org Country, Spain, were eligible to participate in a two-phase prevalence survey. A random stratified one-stage cluster sampling by census areas (n ⫽ 7) was drawn from the sampling frame of households using 1991 and 1995 census data for men and women, respectively. Subjects were recruited by mail and by telephone. All eligible participants in a household were invited to take part in the study. The criteria for exclusion were as follows: tracheostomy, serious physical or mental disability, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. The study was done between July 1993 and November 1997. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Txagorritxu Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the first phase of the study as well as from those selected for overnight polysomnography (second phase). Procedure The first phase of the study included a home-structured interview and sleep recording for one night with the MESAM IV portable recording system. Questionnaires were administered by trained interviewers and included questions on sleep-related breathing disturbances from the Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (15), and questions about respiratory symptoms, medical history, medication use, alcohol consumption, smoking history, and demographic and anthropometric information (height and weight were self-reported). Copies of the interview questionnaire can be obtained from the authors. Habitual snoring was defined as snoring more than 5 d/wk. Information on snoring was primarily obtained from bedpartners (78% of cases), respondents living alone (17% of cases), or other persons living at home (5% of cases). Daytime hypersomnolence (synonymous with excessive daytime sleepiness) was defined as sleepiness at least 3 or more d/wk during the past 3 mo in one or more of the following: after awakening, during free time (leisure time), at work or driving, or during daytime in general. A limited physical examination was performed in which the neck circumference, the peak expiratory flow, and the blood pressure were measured. The neck circumference was measured with a tape measure. The peak expiratory flow was measured with a peak-flow meter (MiniWright; HS International, Clement Clarke International, Ltd, E Dinbur, UK). Blood pressure was measured before and after administration of the questionnaire with a mercury sphygmomanometer with the subject seated following the recommendations of the American Heart Association (16). The mean value of these two measures was used for analysis. All interviewers had successfully completed a control phase of 20 video-simulated situations with different degrees of difficulty without significant deviation in the results obtained. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ⭓ 140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (phase V) ⭓ 90 mm Hg in subjects not taking antihypertensive drugs or self-reporting on current antihypertensive medication. Among the subjects diagnosed as hypertensive, the proportion of cases with systolic blood pressure ⭓ 140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ⭓ 90 mm Hg in people not taking antihypertensive drugs was 75% (81% in men and 66% in women). The MESAM IV (Medizintechnik für Artz und Patient, Munich, Germany) is a four-channel digital recording system that has been previously validated (17, 18). The system records heart rate, snoring, oxygen saturation, and body position and allows both automatic and manual scoring of the recordings. In the second phase of the survey, all subjects tentatively diagnosed as having OSAH with the portable recording system and a random sample of subjects with negative findings were invited to attend the sleep laboratory for overnight polysomnography. The polysomnography consisted of continuous polygraphic recordings (Alice 3; Respironics Inc., Pittsburgh, OH) from surface leads for electroen- 686 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF RESPIRATORY AND CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE VOL 163 2001 cephalography (C3/A2 and C4/A1 placements), electrooculography, tibialis electromyography, and electrocardiography, and from noninvasive sensors for nasal and oral airflow (thermistry), tracheal sounds (microphone), thoracic and abdominal respiratory effort (belt sensors, Healthdyne piezoelectric gauge), and oxyhemoglobin level (finger-pulse oximeter [model 340; Palco Laboratories]). The polysomnography records were manually scored using conventional criteria (19). Each 30s epoch of the recording was scored for sleep stage, breathing, oxygenation, and movement. An abnormal breathing event was defined according to the commonly used clinical criterion of a complete cessation of airflow for ⭓ 10 s (apnea) or a discernible 50% reduction in respiratory airflow accompanied by a decrease of ⭓ 4% in oxyhemoglobin saturation and/or an electroencephalographic arousal (hypopnea). An arousal was defined according to the American Sleep Disorders Association (20). The total number of scored apneas and hypopneas divided by the number of hours of sleep (AHI) was determined for each participant as the summary measure of sleep-disordered breathing. For descriptive analyses, AHI cutoff points of ⭓ 5, ⭓ 10, ⭓ 15, ⭓ 20, and ⭓ 30 were used. The percentage of subjects who had oxygen saturation (SaO2) ⬍ 90% at least 30% of the time was also calculated. The maximal allowable interval between nocturnal MESAM and polysomnography was 2 mo. Statistical Analysis Data analysis was done with common statistical software packages, such as Statistical Analysis Systems (Version 6.12; SAS, Cary, NC) and SUDAAN (Version 7.11). To account for the two-phase design, the analysis was weighted to give unbiased estimates, and the SUDAAN software was used to compute appropriate variances for the weighted analyses. Continuous variables were compared with the t test. Differences in proportions between groups were compared by means of the chi-square (2) test. The prevalence odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) calculated using the multiple logistic regression model (21) were used to estimate the association of age and the prevalence of OSAH adjusted by sex and body mass index (BMI). Logistic regression models were fitted to determine the association between AHI (categorized as 0.0, 0.1–4.9, 5.0–14.9, and ⭓ 15) and daytime hypersomnolence, breathing pauses during sleep, habitual snoring, percentage of subjects who had saturation ⬍ 90% at least 30% of the time, and hypertension. The crude OR and 95% CI for each variable by AHI category and the OR adjusted for confounders (age, sex, peak expiratory flow, BMI, neck circumference, alcohol use, and smoking habit) were calculated. RESULTS A flow-chart of the study population is shown in Figure 1. Of a total of 2,794 eligible subjects, 81% agreed to take part in the Figure 1. Flow chart of the study and number of persons that completed the first and second phases. study and 95% of these completed the first phase of the survey. Results of MESAM were suggestive of OSAH in 442 (21%) patients. A final sample of 390 patients with a tentative diagnosis of OSAH (255 men, 135 women) and 165 (69 men, TABLE 1. DATA OF 2,148 PATIENTS WHO COMPLETED THE FIRST PHASE OF THE STUDY ACCORDING TO RESULTS OBTAINED WITH THE PORTABLE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM (MESAM IV) STRATIFIED BY GENDER Men Data Age, yr Body mass index, kg/m2 Body mass index ⬎ 30 kg/m2, % Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg Hypertension, % Sleep during the week, h Sleep at weekend, h MESAM IV, manual scoring results Agreed to participate§ Did not agree to participate§ Women OSAH (n ⫽ 283) No OSAH (n ⫽ 767) OSAH (n ⫽ 159) No OSAH (n ⫽ 939) 52.0 (9.9)*,† 27.5 (3.4)† 22† 131.4 (17.1)‡ 82.5 (10.1)‡ 38‡ 7.0 (1.4) 7.8 (1.7) 23.5 (13.7) 23.8 (14.1) 21.3 (10.4) 47.4 (10.8) 25.7 (2.9) 8 129.0 (16.4) 81.2 (9.2) 31 7.1 (1.3) 7.9 (1.4) 4.7 (3.2) 5.4 (3.3) 4.7 (2.4) 55.5 (11.3)† 28.4 (6.0)† 32† 129.8 (19.1)† 80.0 (11.2)† 44† 7.0 (1.6) 7.5 (1.7) 22.5 (11.0) 21.9 (9.3) 22.5 (11.3) 46.9 (10.5) 24.5 (3.9) 18 120.8 (16.6) 76.4 (18.2) 18 7.1 (1.3) 7.8 (1.5) 4.3 (3.1) 6.2 (4.2) 5.4 (3.9) Definition of abbreviation: OSAH ⫽ obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea. * Data expressed as mean (SD). † OSAH versus no OSAH, p ⬍ 0.001. ‡ OSAH versus no OSAH, p ⬍ 0.05. § Data corresponding to the subsample of subjects invited to participate in the second phase of the study. 687 Durán, Esnaola, Rubio, et al.: OSAH and Related Clinical Features TABLE 2. AGE-SPECIFIC PREVALENCE RATES OF OSAH AT DIFFERENT SCORES OF THE APNEA–HYPOPNEA INDEX BASED ON POLYSOMNOGRAPHIC RESULTS FOR THE TOTAL SAMPLE OF 1,050 MEN AND 1,098 WOMEN Percentage of Subjects (95% Confidence Interval) ⭓5 ⭓ 10 ⭓ 15 ⭓ 20 ⭓ 30 26.2 (20–32) 9.0 (2–16) 25.6 (14–37) 27.9 (17–38) 52.1 (33–71) 19.0 (14–24) 7.6 (0–15) 18.2 (9–27) 24.1 (15–34) 32.2 (17–48) 14.2 (10–18) 2.7 (1–5) 15.5 (7–24) 19.4 (11–27) 24.2 (12–37) 9.6 (7–12) 2.1 (0–4) 10.1 (5–15) 14.7 (8–21) 15.0 (8–22) 6.8 (5–9) 2.1 (0–4) 7.0 (3–11) 11.4 (6–17) 8.6 (4–14) 28.0 (20–35) 3.4 (0–7) 14.5 (3–25) 35.0 (20–50) 46.9 (31–63) 14.9 (9–20) 1.7 (0–4) 9.7 (0–19) 16.2 (5–27) 25.6 (13–38) 7.0 (3–11) 0.9 (0–2) 6.0 (2–9) 2.9 (0–5) 8.6 (1–17) 15.9 (6–26) 8.3 (0–16) 13.0 (3–22) 4.3 (0–10) 5.9 (0–13) Data Men All ages, yr 30–39 40–49 50–59 60–70 Women All ages, yr 30–39 40–49 50–59 60–70 Definition of abbreviation: OSAH ⫽ obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea. 96 women) from a subsample of 305 diagnosed as not having OSAH underwent polysomnography. Subjects who agreed to undergo polysomnography and those who refused in both subsamples of patients with and without OSAH according to results of MESAM showed similar frequencies with regard to their responses to all questionnaire items on sleep characteristics, body habitus, sex, and age. Results of the 2,148 subjects who completed the first phase of the study stratified by sex are shown in Table 1. Both men and women tentatively diagnosed as having OSAH by MESAM were significantly older, had a higher BMI, and a higher prevalence of hypertension than subjects diagnosed as not having OSAH. Habitual snoring was found in 35% of the population, breathing pauses in 6%, and daytime hypersomnolence in 18%. According to sex, habitual snoring occurred in 46% of men and 25% of women and showed a significant trend to increase with age (from 35% and 11% in the 30–39 year age group to 49% and 41% in the 60–70 yr age group for men and women, respectively). Breathing pauses during sleep on at least 3 d/wk were reported by 10% of men and 2.5% of women and also increased with age. Daytime hypersomnolence found in 14% of men and 22% of women was not associated with age. A wide range of sleep-disordered breathing, ranging from AHI scores of 0 to 120 in men and of 0 to 59 in women, was found. Criteria of AHI values ⭓ 10 on polysomnography were not met by 45.1% of men and 65.4% of women diagnosed as having OSAH by MESAM, whereas 5.8% of men and 11.2% of women not suspected of having OSAH met criteria on polysomnography. The cumulative proportion of subjects with OSAH was similar in both sexes for AHI values ⬍ 8, but thereafter men had a greater prevalence of OSAH than women. Prevalence estimates for different cutoff points of AHI are shown in Table 2. Men had a higher prevalence of OSAH than women in all age groups and at all cutoff points for the AHI ⭓ 5 except for the stratum 50–59 yr at the ⭓ 5 cutoff point. The prevalence of OSAH increased with age in both sexes, with an OR of 2.2 (95% CI, 1.7 to 3.0) for a 10-yr increase and for an AHI ⭓ 5. The male/female OR adjusted by age and BMI increased from 1.2 (95% CI, 0.7 to 2.0) for a cutoff point of ⭓ 5 to 3.0 (95% CI, 1.1 to 8.2) for a cutoff point of ⭓ 30. The association between different scores of AHI and clinical features of OSAH adjusted by age, sex, and peak expiratory flow is shown in Table 3. Breathing pauses during sleep, habitual snoring, and the percentage of subjects who had satu- TABLE 3. ODDS RATIO (OR) AND 95% CONFIDENCE INTERVALS (95% CI) FOR CLINICAL FEATURES OF OSAH BY AHI CATEGORY BASED ON POLYSOMNOGRAPHIC RESULTS OR and 95% CI for Clinical Features of OSAH Daytime hypersomnolence Crude Adjusted for age and sex Breathing pauses during sleep Crude Adjusted for age and sex Habitual snoring Crude Adjusted for age and sex Percentage of subjects with SaO2 ⬍ 90% at least 30% of the total sleep time Crude Adjusted for age, sex, and peak expiratory flow AHI Category 5.0–14.9 ⭓ 15 0 0.1–4.9 1.0 1.0 0.81 (0.4 to 1.7) 0.98 (0.4 to 2.2) 1.37 (0.6 to 3.1) 1.37 (0.6 to 3.3) 1.0 1.0 0.54 (0.1 to 3.0) 0.42 (0.1 to 2.4)* 4.63 (0.8 to 28.4) 4.51 (0.8 to 26.4)* 1.0 1.0 2.88 (1.4 to 5.9) 2.63 (1.2 to 5.6)† 3.36 (1.5 to 7.7) 3.20 (1.4 to 7.5)† 5.45 (2.4 to 12.2) 4.72 (1.9 to 11.5)† 1.0 3.71 (1.4 to 9.6) 3.46 (1.5 to 8.3) 15.57 (7.31 to 34.3) 1.0 2.69 (1.0 to 7.3)† 3.35 (1.3 to 8.7)† 9.74 (4.1 to 23.0)† Definition of abbreviations: AHI ⫽ apnea–hypopnea index; OSAH ⫽ obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea. * p (trend): 0.0002. † p (trend): 0.0001. 1.05 (0.3 to 2.2) 1.05 (0.3 to 3.3) 13.40 (2.6 to 70.5) 9.74 (1.8 to 51.7)* 688 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF RESPIRATORY AND CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE VOL 163 2001 TABLE 4. ODDS RATIO (OR) AND 95% CONFIDENCE INTERVALS (95% CI) FOR HYPERTENSION BY AHI CATEGORY BASED ON POLYSOMNOGRAPHIC RESULTS AHI Category Hypertension* Odds ratio (95% CI) Crude Adjusted for age and sex Adjusted for BMI and neck circumference Adjusted for BMI, neck circumference, alcohol use, and smoking habit 0 (n ⫽ 117) 0.1–4.9 (n ⫽ 169) 5.0–14.9 (n ⫽ 115) ⭓ 15 (n ⫽ 151) 1.0 3.74 (1.69 to 8.31) 3.07 (1.26 to 7.51) 6.46 (2.79 to 14.95) 1.0 2.76 (1.19 to 6.41) 1.70 (0.68 to 4.29) 2.91 (1.19 to 7.07) 1.0 2.58 (1.09 to 6.09) 1.37 (0.56 to 3.36) 2.25 (0.90 to 5.63) 1.0 2.47 (1.06 to 5.76) 1.30 (0.54 to 4.14) 2.28 (0.92 to 5.66) Definition of abbreviations: AHI ⫽ apnea–hypopnea index; BMI ⫽ body mass index. * Age, BMI, neck circumference, and alcohol use taken as continuous variables. Smoking habit categorized as never smoker, ex-smoker, and current smoker. ration ⬍ 90% for at least 30% of the time were significantly associated with OSAH. By contrast, daytime hypersomnolence was not associated with OSAH. As shown in Table 4, AHI was associated with hypertension after adjustment for age, sex, BMI, neck circumference, alcohol use, and smoking habit. DISCUSSION This study confirms that OSAH is very prevalent in the general population and that the frequency of this disorder increases with age. The present results are strengthened by the very high response rate of 81%. Our findings of habitual snoring in 35% of the population, breathing pauses in 6%, and daytime hypersomnolence in 18% are consistent with those found by others (13, 22, 23) and indicate that symptoms of OSAH are common in the general population. In contrast, evidence on the prevalence of OSAH in the general population using conventional polysomnography is lacking. In a random sample of 1,255 employed people 30–60 yr old, Young and coworkers (13) found that 9% of women and 24% of men met minimal criteria for OSAH, and when results were extrapolated to the general population, it was estimated that 2% of women and 4% of men had OSAH syndrome. In a general random sample of 741 men aged 20–100 yr, Bixler and coworkers (14) reported AHI ⭓ 10 and daytime symptoms in 3.3% of the sample. Data on participation by census area for both men and women reveal that participation was lower for men in census area 1 and for women in census areas 1 and 2, but the estimated prevalence of OSAH for the different AHI cutoff points did not vary significantly when these areas were excluded from the calculations (data not shown). We found that the overall prevalence of OSAH of 26.7% was higher in our general population (26.2% in men and 28% in women with AHI ⭓ 5) than that reported by Young and coworkers (13) in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. This may be explained by differences in the health status of the population (healthy worker effect in Young’s study), in the age span (30 to 60 yr in the study of Young and coworkers (13) versus 30 to 70 yr in our study), in the definition of hypopnea (arousal criterion was not applied in the study of Young and coworkers), or in the ethnic characteristics of the populations (only white people in our sample) (24). Discrepancies encountered were more relevant for women than for men. In the Wisconsin study (13), men were 2.0 to 3.7 times as likely as women to have sleep-disordered breathing, whereas when data in our study were adjusted by age and BMI, the male/female OR were 1.2 and 3.0 for an AHI ⭓ 5 and ⭓ 30, respectively. Most studies had shown how the prevalence of OSAH increases with age (13, 14, 25, 26). Redline and coworkers (25) carried out a study on 390 community residents of the Cleveland Family Study, from children to older aged people, and found that prevalence rates for an AHI ⭓ 5 increased close to fivefold for the group younger than 25 yr of age to subjects over 60 yr of age and that this increase was also consistent for higher AHI cutoff values. In the Wisconsin study (13), there was a pattern of increasing prevalence with age for AHI ⭓ 5 being less evident for AHI ⭓ 10 or ⭓ 15. We found a strong association between AHI and age in the logistic regression model adjusted by sex and BMI, suggesting that factors other than obesity play a role in the presence of OSAH. The definition of OSAH is arbitrary and it has been suggested than an AHI ⭓ 5 is a too low cutoff value, especially for elderly people (27, 28). Recently, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) (29) proposed a consensus definition for OSAH syndrome based on an AHI ⭓ 5 plus symptoms. The prevalence of OSAH syndrome of 4% in men and 2% in women estimated by Young and coworkers (13) was based on AHI score of 5 or higher and moderate to severe daytime hypersomnolence. In a sample of a male population using a definition of OSAH syndrome of AHI ⭓ 10 plus daytime sleepiness, hypertension, or another cardiovascular complications, Bixler and coworkers (14) found a prevalence of 3.3%. According to an AHI ⭓ 10 plus excessive daytime sleepiness, the prevalence of OSAH syndrome in our population was 3.4% in men and 3% in women. In our study, daytime hypersomnolence was found in 21% of men and 26% of women with AHI ⭓ 5, but excessive sleepiness was also found in 12% of the men and 28% of the women with AHI ⬍ 5. Thus, excessive daytime hypersomnolence is highly prevalent both in patients with and without OSAH. Moreover, a significant association between daytime hypersomnolence and OSAH was not found. On the other hand, self-reported sleepiness is not an objective measure and it underestimates the physiological state of sleepiness (30). Thus, it seems difficult to accurately define OSAH syndrome in the general population according to a low AHI score and excessive daytime sleepiness. In contrast to a systematic review in which no firm evidence for the contribution of OSAH to hypertension was demonstrated (31), it has been recently shown that sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension are clearly linked (32–35). In agree- Durán, Esnaola, Rubio, et al.: OSAH and Related Clinical Features ment with these findings, a significant association of AHI with hypertension was found after adjusting for demographics (age, sex) and anthropometric variables (including BMI and neck circumference), as well as for alcohol intake and smoking. In our study, however, the odds ratio of hypertension did not increase by AHI category, which is in contrast to data found in patients referred to the sleep clinic with suspected sleep apnea syndrome (33). In this study, Lavie and coworkers (33) showed that each additional apneic event per hour of sleep increased the odds of hypertension by 1%. Young and coworkers (32), also showed that the prevalence of hypertension trended to increase with increasing severity of sleep-disordered breathing. A dose–reponse association between sleepdisordered breathing at baseline and the presence of hypertension 4 yr later that was independent of known confounding factors was found in the prospective, population-based study of Peppard and coworkers (34). The relatively small sample size in our study compared with the large number of participants in studies reported by other authors (32–35) may account for our observation of a nonincreasing trend in the odds ratios for the presence of hypertension comparing the highest and the lowest category of AHI. In summary, we found that the prevalence of OSAH in the general population was high and increased with age in both sexes. Habitual snoring and breathing pauses were significantly associated with OSAH. This study adds evidence for a link between OSAH and hypertension. Acknowledgment : Joaquín Durán and Santiago Esnaola were the principal investigators, designed the protocol, collected data, and wrote the paper. Ramón Rubio and Joaquín Durán analyzed polysomnographic and polygraphic recordings. Santiago Esnaola performed the statistical analysis. Ángeles Iztueta designed the sampling plan. The final draft was revised and approved by all authors. The authors are grateful to Dr. E. Gorostiza for training the interviewers in the blood pressure measurement, to J. M. Montserrat, E. Ballester, and D. Rodenstein for reading the draft and for helpful comments on the manuscript, to M. Partinen for the use of the Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire, to T. Calleja, G. De La Torre, B. Larrauri, and I. Toña for technical contributions to the study, and to Marta Pulido for editing the manuscript and editorial assistance. The MESAM IV devices used for nocturnal respiratory polygraphic recordings were kindly lent by Medizintechnik für Arz und Patient from Munich, Germany. References 1. Guilleminault C. Clinical features and evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea. In: Krieger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1989. p. 552–558. 2. Diagnostic Classification Steering Committee of the American Sleep Disorders Association. The international classification of sleep disorders: diagnostic and coding manual. Rochester, MN: American Sleep Disorders Association; 1990. 3. Hung J, Whitford EG, Parsons RW, Hillman DR. Association of sleep apnea with myocardial infarction in men. Lancet 1990;336:261–264. 4. Partinen M, Guilleminault C. Daytime sleepiness and vascular morbidity at seven-year follow-up in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Chest 1990; 97:27–32. 5. Redline S, Strauss ME, Adams N, Winters M, Roebuck T, Spry K, Rosenberg C, Adams K. Neuropsychological function in mild sleepdisordered breathing. Sleep 1997;20:160–167. 6. He J, Kryger MH, Zorick FJ, Conway W, Roth T. Mortality an apnea index in obstructive sleep apnea: experience in 385 male patients. Chest 1988;94:9–14. 7. Bliwise DL, Bliwise NG, Partinen M, Pursley AM, Dement WC. Sleep apnea and mortality in an aged cohort. Am J Public Health 1988;78:544–547. 8. Lavie P, Herer P, Peled R, Berger I, Yoffe N, Zomer J, Rubin AE. Mortality in sleep apnea patients: a multivariate analysis of risk factors. Sleep 1995;18:149–157. 9. Young T, Blustein J, Finn L, Palta M. Sleep-disordered breathing and motor vehicle accidents in a population-based sample of employed adults. Sleep 1997;20:6081–613. 10. Terán-Santos J, Jiménez-Gómez A, Cordero-Guevara J, and the Cooperative Group Burgos–Santander. The association between sleep ap- 689 nea and the risk of traffic accidents. N Engl J Med 1999;340:847–851. 11. Barbé F, Pericás J, Muñoz A, Findley L, Antó JM, Agustí AGN. Automobile accidents in patients with sleep apnea syndrome: an epidemiological and mechanistic study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158: 18–22. 12. Phillipson EA. Sleep apnea—a major public health problem. N Engl J Med 1999;328:1271–1273. 13. Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med 1993;328:1230–1235. 14. Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Ten Have T, Tyson K, Kales A. Effects of age on sleep apnea in men: I. Prevalence and severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:144–148. 15. Partinen M, Gislason T. Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ): a quantitated measure of subjective sleep complaints. J Sleep Res 1995; 4(Suppl 1):150–155. 16. Perloff D, Grim C, Flack J, Frohlich ED, Hill M, McDonald M, Morgenstern BZ. Human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometry. Circulation 1993;88:2460–2470. 17. Stoohs R, Guilleminault C. Mesam 4: an ambulatory device for the detection of patients at risk for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS). Chest 1992;101:1221–1227. 18. Esnaola S, Durán J, Infante-Rivard C, Rubio R, Fernández A. Diagnostic accuracy of a portable recording device (Mesam IV) in suspected obstructive sleep apnea. Eur Respir J 1996;9:2597–2605. 19. Rechtschaffen, A, Kales, A.A. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1968. NIH Publication No. 204. 20. American Sleep Disorders Association—The Atlas Task Force. EEG arousals: scoring rules and examples. Sleep 1992;15:174–184. 21. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: John Wiley; 1989. 22. Ohayon MM, Guilleminault C, Priest RG, Caulet M. Snoring and breathing pauses during sleep: telephone interview survey of a United Kingdom population sample. BMJ 1997;314:860–863. 23. Olson LG, King MT, Hensley MJ, Saunders NA. A community study of snoring and sleep-disordered breathing: symptoms. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152:707–710. 24. Redline S, Tishler PV, Hans MG, Tosteson TD, Strohl KP, Spry K. Racial differences in sleep-disordered breathing in African-Americans and caucasians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:186–192. 25. Redline S, Tishler PV, Avlor J, Clark K, Burant C, Winters J. Prevalence and risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in children [abstract]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:A843. 26. Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, Mason WJ, Fell R, Kaplan O. Sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep 1991; 14:486–495. 27. Phillips BA, Berry DTR, Lipke-Molby TC. Sleep-disordered breathing in healthy, aged persons: fifth and final year follow-up. Chest 1996; 110:654–658. 28. Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, Fell R, Stepnowsky C, Estline E, Khazeni N, Chinn A. Morbidity, mortality and sleep-disordered breathing in community dwelling elderly. Sleep 1996;19:277–282. 29. American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. Sleep 1999;22:667–689. 30. Thorpy MJ. The clinical use of the multiple sleep latency test: the standards of Practice Committee of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Sleep 1992;15:268–276 [Erratum. Sleep 1992;15:381]. 31. Wright J, Jonhs R, Watt I, Melville A, Sheldon T. The health effects of obstructive sleep apnea and the effectiveness of continuous positive airways pressure: a systematic review of the research evidence. BMJ 1997;314:851–860. 32. Young T, Peppard P, Palta M, Hla KM, Finn L, Morgan B, Skatrud J. Population-based study of sleep-disordered breathing as a risk factor for hypertension. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:1746–1752. 33. Lavie P, Herer P, Hofstein V. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome as a risk factor for hypertension: population study. BMJ 2000;320:479–482. 34. Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1378–1384. 35. Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, Shahar E, Samet JM, Redline S, D’Agostino RB, Newman AB, Lebowitz MD, Pickering TG. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study: Sleep Hearth Health Study. JAMA 2000;283: 1829–1836.