as a PDF

advertisement

Averaging lemmas without time Fourier transform

and application to discretized kinetic equations

F. Bouchut and L. Desvillettes

Universite d'Orleans et CNRS, UMR 6628

Departement de Mathematiques

BP 6759

45067 Orleans cedex 2, France

e-mail: fbouchut@labomath.univ-orleans.fr, desville@labomath.univ-orleans.fr

Abstract

We prove classical averaging lemmas in the L2 framework with the help of

the Fourier transform in variables x and v , but not t. Then, this method is used

in order to study discretized problems issued of the numerical analysis of kinetic

equations.

Key-words. Kinetic equations, discrete averaging lemmas, splitting method, implicit

methods.

Les lemmes de moyenne sans transformee de Fourier en temps et

application aux equations cinetiques discretes

Resume

Nous montrons les lemmes de moyenne classiques dans le contexte

par transformation de Fourier dans les variables x et v, mais pas t.

Nous appliquons cette methode a l'etude de problemes discrets issus de

l'analyse numerique des equations cinetiques.

Mots-cles. Equations cinetiques, lemmes de moyenne discrets, methode des pas fractionnaires, methodes implicites.

L2

1991 Mathematics Subject Classication. Primary 76P05, 35B35, 65M12.

1

1 Introduction

Averaging lemmas have been introduced in [8] and [7] for the study of kinetic equations,

and have been developed in the works of [3], [5], [6], [4], [1], [12], [10], and more recently

in [14].

Roughly speaking, they state that if f = f (x; v) (resp. f = f (t; x; v)) and v rxf

(resp. @tf + v rxf ) belong to a given space (typically L2), then for any smooth

function , the average quantity (f )(x) = v2RN f (x; v) (v) dv (resp. (f )(t; x) =

1=2

v2RN f (t; x; v ) (v ) dv ) lies in a "better" space (H in the previous example).

The proof of such a property usually requires to Fourier transform the equation in

the x variable (resp. in the t; x variables), but not in the v variable.

We propose here a slightly dierent proof, which makes sense only in the case when

f depends on the time variable t. This proof makes use of the Fourier transform in

both x and v, but not in t. Consequently, it is better adapted to the case of functions

only dened on [0; T ] RNx RNv , and not on the whole space Rt RNx RNv. However, it

only provides the regularity of in space (and not in time). This procedure was used

by F. Golse [6] and by P.-L. Lions and B. Perthame [11] in the case when no derivative

with respect to v occurs in the right-hand side, and when the transport operator is

@t + v r x .

In Sections 2 and 3 of this paper, we extend these results in the case when general

advection operators @t + a(v) rx are considered, and when derivatives with respect to

v are involved.

The interest of this method lies in the fact that it yields results when some discretization in time is in order. Such a situation is described in [2]. In this work, the

operator splitting technique between the free transport part and the collisional part of

the Boltzmann equation is studied, in the framework of renormalized solutions.

For example, we are able to prove that if both f and @tf + v rxf lie in L2, then

a Riemann sum of the type

T m (f )(n T ; x)

Rm (f )(x) = m

(1.1)

m

n=1

is of order O( p1m ) for large wavevectors. Such a result does not seem so easy to get

when a Fourier transform in the time variable is performed. In Sections 4 and 5, we

investigate averaging lemmas which involve such Riemann sums and also various time

discretizations issued of the numerical analysis of kinetic equations.

R

R

X

Throughout the paper, we shall denote by C (resp. CN , CN; , etc.) any absolute

constant (resp. any constant at most depending on N , N and , etc.).

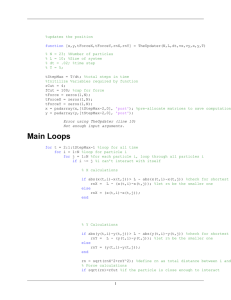

2 Linear coecient

Let us consider the standard averaging lemma with a derivative with respect to v in

the right-hand side, which was originally obtained in [3]. We give here a dierent proof,

2

with a slightly weaker conclusion.

Theorem 2.1 Let f 2 C ([0; T ]; L2(RNx RNv) ? w) solve the transport equation

@tf + v rxf = g + divv h in ]0; T [RNx RNv ;

(2.1)

for some g; h 2 L2(]0; T [RNx RNv ). Then, for any 2 Cc1 (RN ), the average quantity

Z

(t; x) = RN f (t; x; v) (v) dv

(2.2)

lies in L2 (]0; T [; H 1=4(RNx )), and

k kL2 (]0;T [;H 1=4(RNx)) C kf (0; )kL2 (RNxRNv) + kf kL2 (]0;T [RNxRNv)

+kgkL2(]0;T [RNxRNv) + khkL2 (]0;T [RNxRNv) :

(2.3)

Proof. First, notice that 2 C ([0; T ]; L2(RNx ) ? w), and for any t 2 [0; T ],

k (t; )kL2(RNx) k kL2(RNv) kf (t; )kL2(RNxRNv);

(2.4)

k kL2(]0;T [RNx) k kL2(RNv) kf kL2(]0;T [RNxRNv):

(2.5)

Let us denote f0 = f (0; ), f (t; ; v) the Fourier transform of f in the x variable, and

F f (t; ; ) the Fourier transform of f in the x; v variables. Then, (2.1) yields

@tf + i v f = g + divv h:

(2.6)

Next, we consider a strictly positive function = () 2 C 1(RN), which will be chosen

b

b

b

b

b

later on, and write (2.6) as

@tf + ( + i v )f = f + g + divv h:

Solving this equation in the sense of distributions, we get

b

b

b

b

(2.7)

b

Z t

?

(

+

i

v

)

t

b

f0(; v) + e?(+i v)s(fb + gb + divv hb )(t ? s; ; v) ds:

f (t; ; v) = e

b

0

(2.8)

Multiplying (2.8) by (v), we obtain

f (t; ; v) (v) = e?(+i v)tf0 (; v)

t

(2.9)

+ e?(+i v)s f + g ? h r + divv h (t ? s; ; v) ds;

b

d

Z

0

d

c

b

d

and after integration in v,

b

Z

t ?s e F (f

)(t ? s; ; s)

)(; t) +

0

(2.10)

+ F (g ? h r )(t ? s; ; s) + is F (h )(t ? s; ; s) ds:

(t; ) = e?tF (f

0

3

This type of formula with double Fourier transform evaluated at (; t) was introduced

in [6]. For a.e. 2 RN, we estimate this quantity thanks to the Cauchy{Schwarz

inequality with weight e?s, and get

Z

t

Z

t

j (t; )j2 2e?2tjF (f0 )(; t)j2 + 6 0 e?s ds 0 e?s

(2.11)

2 jF (f )(t ? s; ; s)j2 + jF (g ? h r )(t ? s; ; s)j2

+ s2jj2 jF (h )(t ? s; ; s)j2 ds:

b

Integrating this estimate on ]0; T [, and using the variable = t ? s, we get

Z

T

0

j (t; )j2 dt 2 0 e?2tjF (f0 )(; t)j2 dt + 6 0 0 e?s

(2.12)

2 jF (f )(; ; s)j2 + jF (g ? h r )(; ; s)j2

+ s2jj2 jF (h )(; ; s)j2 dsd:

Z

b

T

Z

TZT

Then, using the estimates

sup e?s 1;

s0

sup s2e?s 1=2 ;

(2.13)

s0

we obtain

Z

0

T

b

+1

+1

jF

(f0 )(; t)j2 dt + 6

?1

=0 s=?1

2

2

jF (f )(; ; s)j + jF (g ? h r )(; ; s)j2

2

+ jj2 jF (h )(; ; s)j2 dsd

+1

T +1

(2.14)

= j2j

jF

(f0 )(; z jj )j2 dz + j6j

?1

=0 z=?1

2

2

jF (f )(; ; z jj )j + jF (g ? h r )(; ; z jj )j2

2

j

j

+ 2 jF (h )(; ; z jj )j2 dzd:

j (t; )j2 dt 2

Z

Z

T

Z

Z

Z

Z

Let us now state a very classical trace lemma.

Lemma 2.2 Let 2 H s(RN ) with s > (N ? 1)=2. Then, for any 2 RN such that

jj = 1,

k(z)kL2(z2R) CN;s k(Id ? )s=2kL2 (RN):

(2.15)

4

For each integral in z, we use this lemma and Plancherel's identity. We get for a.e. T

Z

0

j (t; )j2 dt

b

CjN;sj

Z

v2RN

f0 (; v) (1 + jvj2)s dv + CN;s

jj

2

d

Z

T

Z

=0 v2RN

2

2

2 f (; ; v) + (g ? h r )(; ; v) + jj2 h (; ; v) (1 + jvj2)s dvd

2

CN;s k (v) (1 + jvj2)s=2kL (RNv) + kr (v) (1 + jvj2)s=2kL (RNv)

T

j1j v2RN f0(; v) 2 dv + jj =0 v2RN f (; ; v) 2 dvd

T

2

2 + jhj2 (; ; v ) dvd + j j T

+ 1

j

g

j

dvd :

h

(

;

;

v

)

3

jj =0 v2RN

=0 v2RN

(2.16)

1

=

2

2

2

1

=

4

Finally, we choose = jj (take () = ( + jj ) and let go to 0). Integrating

this estimate on the set fjj > 1g, and using (2.5) for the set fjj 1g, we obtain the

result.

d

2

c

b

2

d

1

1

Z

b

Z

Z

Z

Z

b

b

b

Z

Z

b

Remark 2.3 If h = 0, we actually get 2 L2(]0; T [; H 1=2(RNx)) by choosing constant.

In this case, the above proof is very close to the higher moments lemmas, see [11], [13].

We could treat in the same way the case when a derivation of order larger than one in

v occurs in the right-hand side of the transport equation.

3 Nonlinear coecient

Let us now consider a nonlinear coecient a 2 L1loc(RM ; RN), and the associated transport operator @t +a(v)rx. It appears either in relativistic or quantum kinetic equations

[9], with M = N ; or in the kinetic formulation of scalar conservation laws [12], with

M = 1. In this situation, a non-degeneracy assumption on a is necessary to get the

regularity of averages in v. Namely, for any direction 2 S N ?1, a(v) has to be

non-constant, otherwise the averaging procedure would not give any regularity in x in

the direction (take f of the form f = '(x ? t a(v) )). With an estimate of

this non-degeneracy, the authors of [7], [4] and [12] were able to prove the regularity

in (t; x) of the averages with respect to v. We give here a new proof of this regularity,

in the same spirit as Theorem 2.1.

Theorem 3.1 Let a 2 Liploc (RM; RN ) and 2 H 1(RM ), such that for some K 0

and 0 < 1, one has

8 2 S N ?1;

If

8u 2 R; 8" > 0;

Z

j (v)j2 + jr (v)j2 dv K":

u<a(v)<u+"

(3.1)

is not compactly supported, we assume moreover that ra is globally bounded.

5

Let f 2 C ([0; T ]; L2(RNx RM

v ) ? w) solve

@tf + divx[a(v)f ] = g + divv h in ]0; T [RNx RMv ;

(3.2)

for some g; h 2 L2 (]0; T [RNx RM

v ). Then the average

Z

(t; x) = RM f (t; x; v) (v) dv

belongs to L2 (]0; T [; H =4(RNx )), and

(3.3)

p

k kL2(]0;T [;H =4(RNx)) CN k kL2(RMv) + K kf (0; )kL2 (RNxRMv)

(3.4)

+ kf kL2 (]0;T [RNxRMv) + kgkL2(]0;T [RNxRMv)

+ khkL2(]0;T [RNxRMv) + kra(v) hkL2(]0;T [RNx supp ) :

Remark 3.2 The assumption (3.1) involves both the non-degeneracy of a and the decrease of at innity. Notice that even if M = N and a(v) = v (i.e. the case of

Theorem 2.1), this assumption is weaker than that used in Theorem 2.1 (namely a

decay of in (1 + jvj2)?s=2 with s > (N ? 1)=2). Notice also that if N = 1, one

essentially needs ; r 2 L1 .

Remark 3.3 The non-degeneracy condition (3.1) is very close to those of [7] and [12]

(see Proposition 3.11).

Before proving Theorem 3.1, let us introduce a preliminary estimate of an oscillatory

integral which replaces the Fourier transform in v which was used in the proof of

Theorem 2.1. This estimate treats a stationary phase with high order degeneracy, a

problem that was set in [6].

Lemma 3.4 Let b : RM ! R be a measurable (almost everywhere dened) function,

and 2 L2 (RM ). We assume that there exists a nondecreasing function such that

8u 2 R; 8" > 0;

Z

j (v)j2 dv ("):

u<b(v)<u+"

(3.5)

Then for any > 0 and f 2 L2 (RM),

2

1

p1 +1 2z2 RM e?izb(v) f (v) (v) dv

2 0 e?t(t) dt kf k2L2(RM):

L2 (z2R)

Z

Z

6

(3.6)

Proof. Let (u) = 1Iu>0 e?u, so that (z) = 1=(1 + iz). Consider the function

1 b(v) ? u f (v) (v) dv 2 L1(R):

(u) =

b

!

Z

RM We have

(z) = (?z)

b

b

Z

RM

e?izb(v) f (v) (v) dv;

(3.7)

(3.8)

and thus we have to estimate kk2L2(R) = 2kk2L2(R). For a.e. u, we get by using the

Cauchy-Schwarz inequality

(3.9)

j(u)j2 RM 1 b(v)? u j (v)j2 dv RM 1 b(v)? u jf (v)j2 dv:

Lemma 3.5 Let ' 2 C 1([0; 1[) be a nonnegative nonincreasing function such that

'!

1 0, (V; ) be a -nite measure space, and w : V ! [0; 1[ be a measurable function

dened a.e. Then

b

!

Z

Z

Z

!

Z

1

'(w(v)) (dv) = 0 ?'0(t) (fv 2 V ; w(v) < tg) dt:

V

(3.10)

This identity is easily obtained by applying Fubini's theorem to

ZZ

?1Iw(v)<t '0(t) dt(dv):

(3.11)

]0;1[V

End of the proof of Lemma 3.4. Choose '(t) = e?t, (dv) = 1Ib(v)>u j (v)j2dv and

w(v) = (b(v) ? u)= . We obtain thanks to Lemma 3.5, and according to assumption

(3.5)

b(v) ? u j (v)j2 dv

!

Z

= '(w(v)) (dv)

1

= ?'0(t) fv ; b(v) ? u < tg dt

01

0 ?'0(t) (t) dt:

Therefore, we deduce from (3.9) that for a.e. u,

1

j(u)j2 1 0 e?t(t) dt RM 1 b(v)? u jf (v)j2 dv;

and after integration in u,

1

kk2L2(R) 1 0 e?t (t) dt kf k2L2 (RM);

and the proof is complete.

RM

Z

Z

Z

!

Z

Z

Z

7

(3.12)

(3.13)

Remark 3.6 Under the assumptions of Lemma 3.4, and if 6 0, we must have

1

(3.14)

lim 1 e?t (t) dt > 0:

0

!0+

In particular, (") cannot tend to 0 faster than " when " ! 0.

Namely, if (3.14) were wrong, then there would exist a sequence n ! 0 such that

1 1e?t ( t) dt ! 0;

n

n 0

and thus for any f 2 L2(RM), the left-hand side of (3.6) would tend to 0. After

extraction of a subsequence, the convergence would hold almost everywhere, so that

for a.e. z 2 R

e?izb(v) f (v) (v) dv = 0:

M

R

But this function is continuous with respect to z, and taking z = 0, we obtain f = 0

for any f 2 L2. Thus 0.

Remark 3.7 If (") = K", with K 0 and 0 < 1, we obtain

Z

Z

Z

R

Z

0

1 ?t

e (t) dt = ?( + 1)K K :

Proof of Theorem 3.1. As in Theorem 2.1, 2 C ([0; T ]; L2(RNx ) ? w), with

k kL2(]0;T [RNx) k kL2(RMv) kf kL2(]0;T [RNxRMv):

(3.15)

We again consider a strictly positive function = () 2 C 1(RN ), and write (3.2) as

@tf + ( + i a(v) )f = f + g + divv h in ]0; T [RN RMv:

(3.16)

b

b

b

b

b

By approximating a by a smooth function, it is possible to justify that

@t e(+ia(v))tf = e(+ia(v))t(f + g)+divv e(+i a(v))th ? e(+ia(v))tit ra(v)h ;

(3.17)

and we obtain for any t 2 [0; T ]

b

b

b

b

Z

t

?

(

+

i

a

(

v

)

)

t

b

f (t; ; v) = e

f0(; v) + e?(+i a(v))s (fb + gb)(t ? s; ; v) ds

0

Z t

?

(

+

i

a

(

v

)

)

s

b

+ divv e

h(t ? s; ; v) ds

0

Z t

h

i

+ e?(+i a(v))s is ra(v)hb(t ? s; ; v) ds:

b

b

0

(3.18)

Let us now dene the operator G , which replaces the Fourier operator F of Theorem

2.1, by the formula

G '(; ) = M e?ia(v)'(; v) dv;

(3.19)

Z

b

R

8

where ' = '(x; v), x 2 RN , v 2 RM, and , 2 RN . Then we obtain

Z

(t; ) = M f (t; ; v) (v) dv

R

t

?

= e tG (f0 )(; t) + e?s G (f )(t ? s; ; s)

0

+ G (g ? h r )(t ? s; ; s) + is G (ra h )(t ? s; ; s) ds:

b

b

Z

(3.20)

Next, we use the same estimates as in Theorem 2.1, except that the estimates (2.13)

are strengthened in the following way

8s 0; e?s 1 +12s2 ; s2e?s 2 (1 +6 2s2) :

(3.21)

We obtain for a.e. 2 RN

+1

T

)j2 dz

1

jG

(

f

)(

;

z

j

(t; )j2 dt j2j

0

2

2

2

jj

?1 1 + z =j j

0

T +1

1

6

2

+ jj =0 z=?1 1 + 2z2=jj2 jG (f )(; ; z jj )j2

(3.22)

2

+ jG (g ? h r )(; ; z )j2 + 6 jj2 jG (ra h )(; ; z )j2 dzd:

jj

jj

Then, we set = =jj, b(v) = a(v) , = =jj, and for each integral in z in (3.22)

we apply Lemma 3.4. We get

Z

Z

b

Z

Z

Z

T

0

j (t; )j2 dt

b

?1

2

2

2

T

dvd

f

(

;

;

v

)

dv

+6

f

(

;

v

)

0

M

M

jj v2R T

jj =0 v2R

(3.23)

6

2

2

+

jj =0 v2RM jgj + jhj (; ; v) dvd

T

2

+ 36 j3j

r

a(v)h(; ; v) dvd :

=0 v2 supp

We conclude as in Theorem 2.1 by choosing () = jj1=2 and by integrating (3.23)

over jj > 1.

2K jj

!

Z

Z

Z

b

Z

b

b

Z

Z

Z

b

b

Remark 3.8 If h = 0 in Theorem 3.1, we actually only have to assume that a 2

L1loc (RM; RN ), 2 L2(RM ), and that (3.1) is satised for (not for r ). In that

case the result is 2 L2(]0; T [; H =2(RNx)). It is obtained by choosing constant in

(3.23). Indeed, by taking = 1=T and by using the explicit formula for the solution

to estimate the norm of f we obtain

p

p

k kL2(]0;T [;H_ =2(RNx)) CN KT (1?)=2 kf (0; )kL2 (RNxRMv) + T kgkL2(]0;T [RNxRMv) :

9

Remark 3.9 If the right-hand side of (3.1) is replaced by ("), with :]0; 1[! [0; 1[

nondecreasing, !0 0, then we obtain that for any R > 1

Z

T

Z

t=0 jj>R

j

b

Z 1

2

(t; )j ddt CN 0 e?t pt dt kf (0; :)k2L2 + kf k2L2 + kgk2L2

R

+khk2L2 + kra hk2L2 ;

!

t dt ?! 0, this provides a local compactness result.

p

and since

0

R R!1

Remark 3.10 The decomposition (3.18) is analogous to the usual one ([7],[4]) in which

the estimates for is performed in a dierent way depending whether ja(v) j < ()

or not. The advantage of (3.18) is that it has a time-space counterpart. Namely,

if () = 0jj , for some 0 > 0, > 0, then dening 1, 2 by 1() = e?jj ,

2() = jj e?jj (i.e. 2(x) = divx[x1(x)= ]), (3.18) yields for any t > 0

f (t; x; v) = ( t1)N= 1 ( tx)1= x f0(x ? ta(v); v)

0

0

t

1

+ ( s)N= 2 ( sx)1= x f (t ? s; x ? sa(v); v) ds

s

0 0

0

t

+ ( s1)N= 1 ( sx)1= x g(t ? s; x ? sa(v); v) ds

0 0

0

t

1

+ divv ( s)N= 1 ( sx)1= x h(t ? s; x ? sa(v); v) ds

0 0

0

t

s

+ divx ( s)N= 1 ( sx)1= x ra(v)h(t ? s; x ? sa(v); v) ds:

0 0

0

This formula should in theory provide the W s;p regularity in x for data in Lp, by

choosing = 1=2 ( = 1 ? 1=(m + 1) for a derivative of order m with respect to v

on the right-hand side). The above integrals appear actually as translation invariant

singular integrals in the variables (t; x). A similar formula is involved in [14] with

= 1.

Let us end this section by a result of almost equivalence between the non-degeneracy

condition (2.2.1) and that of [12].

Z

!

1 ?t

e b

b

b

!

!

Z

!

Z

!

Z

!

Z

Let (V; ) be a nite measure space, and a : V ! RN a measurable function dened

almost everywhere. We introduce three conditions Ht;x, Hx and H on a, which correspond respectively to regularity in (t; x), regularity in x and compactness for averages

in v.

Condition Ht;x There exists :]0; 1[! [0; 1[ nondecreasing, !0 0, such that

8(!; ) 2 S N R RN ; 8" > 0; fv 2 V ; j! + a(v) j < "g ("):

10

Condition Hx There exists :]0; 1[! [0; 1[ nondecreasing, !0 0, such that

8 2 S N ?1; 8u 2 R; 8" > 0; fv 2 V ; u < a(v) < u + "g ("):

Condition H 8 2 S N ?1; 8u 2 R; fv 2 V ; a(v) = ug = 0:

Proposition 3.11 We have the following implications.

(i) Ht;x ) Hx , with the same ,

(ii) Hx ) H ,

(iii) H ) Ht;x for some .

p

p

Proof. (i) Let 2 S N ?1 and u 2 R, and dene = = 1 + u2, ! = ?u= 1 + u2.

Then by Ht;x we have

p

8" > 0; v 2 V ; ja(v) ? uj < " 1 + u2 ("):

p 2

n

o

Therefore, for any given " > 0, we get by setting " = "= 1 + u

fv 2 V ; ja(v) ? uj < "g p " 2 ("):

(3.24)

1+u

(ii) We have for any " > 0

fv 2 V ; a(v) = ug fv 2 V ; u ? "=2 < a(v) < u + "=2g (");

and the result follows.

(iii) That implication was proved in [12]. Condition H is obviously equivalent to

8(!; ) 2 R RN nf(0; 0)g; fv 2 V ; ! + a(v) = 0g = 0;

(3.25)

and also, since is nite, to

0:

(3.26)

8(!; ) 2 R RN nf(0; 0)g; fv 2 V ; j! + a(v) j < "g "?!

!0+

e

e

e

Let us dene

e

!

(") = sup N fv 2 V ; j! + a(v) j < "g :

(!;)2S

e

(3.27)

It only remains to prove that !0 0.

Let > 0. Since is nite, there exists R > 0 such that fv 2 V ; ja(v)j > Rg =2.

For any (!0; 0) 2 S N , thanks to (3.26), there exists !0;0 > 0 such that

(3.28)

80 < " < !0;0 ; fv 2 V ; j!0 + a(v) 0j < "g =2:

Then, for any (!; ) 2 S N such that j! ? !0j + R j ? 0j < !0;0 =2 and 0 < " < !0;0 =2,

we have fv ; ja(v)j R and j! + a(v) j < "g fv ; j!0 + a(v) 0j < " + !0;0 =2g,

and thus fv 2 V ; j! + a(v) j < "g . Finally, by taking a nite covering of S N

by neighborhoods of the form j! ? !0j + R j ? 0 j < !0;0 =2, we obtain that (") for " small enough.

11

4 The splitting method

We prove here the averaging lemma which allows to obtain the convergence of the

operator splitting method for the Boltzmann equation in the renormalized framework

(Cf. [2]). The proof is slightly dierent from that of [2], where Poisson's formula is

used. Let us mention that there exists another method to prove the convergence of the

splitting algorithm, which does not use averaging lemmas, see [15].

We denote by C(r) the space of functions which are right-continuous and bounded.

Theorem 4.1 Let f 2 C(r)([0; T ]; L2(RNx RNv ) ? w) satisfy

@t f + v r x f =

m

X

j =1

(t ? j t)

Z

j t

(j ?1)t

g(; x; v) d in ]0; T ] RNx RNv

(4.1)

for some g 2 L2 (]0; T [RNx RNv ), where t = T=m. Then, for any 2 Cc1 (RN), the

average

Z

(4.2)

(t; x) = N f (t; x; v) (v) dv

R

satises for any R > 0

t

m

X

Z

j (nt; )j2 d

b

n=1 jj>R CT; 1 + t kf (0; :)k2L2 (RNxRNv) + kgk2L2(]0;T [RNxRNv) :

(4.3)

R

Remark 4.2 Notice that the quantity estimated here is a Riemann sum instead of an L2

norm (in the time variable). It is well known that in the L2 context at least, no estimate

1=2

in spaces of the type L1

t (Hx ) can be obtained for . Therefore, the appearance of

a term of order t in (4.3) (which does not tend to 0 when R ! 1) is not surprising.

However, compactness is recovered asymptotically when t ! 0.

Proof of Theorem 4.1. Taking the Fourier transform of (4.1) with respect to x, we

obtain

@tf + i (v ) f =

b

Therefore, for any t 2 [0; T ],

b

m

Z

j t

(t ? j t) (j?1)t g (; ; v) d:

j =1

X

b

(4.4)

Z j t

m Z

X

?

i

(

v

)(

t

?

s

)

?

i

(

v

)

t

b

b

(s?j t) (j?1)t g(; ; v) d ds

f (t; ; v) = e

f0(; v)+ ]0;t] e

j =1

Z j t

(4.5)

X

= e?i(v)tfb0(; v) +

gb(; ; v) d:

e?i(v)(t?jt)

(j ?1)t

0<j t=t

b

12

Then, proceeding as in the proof of Theorem 2.1, we get for n = 0; 1; ::; m

(nt; ) = F (f0 )(; nt ) +

b

n

X

+2nt

j t

j =1 (j ?1)t

j (nt; )j2 2jF (f0 )(; nt )j2

b

Z

n

X

j =1

Z

F (g )(; ; (n ? j )t ) d;

j t

jF

(g )(; ; (n ? j )t )j2 d:

(j ?1)t

(4.6)

Finally, denoting l = n ? j ,

t

m

X

j (nt; )j2

n=1m

b

Z j t

X

2

jF

(g )(; ; (n ? j )t )j2 d

2t jF (f0 )(; nt )j + 2T t

n=1

1j nm (j ?1)t

?j Z j t

m mX

m

X

X

jF (g )(; ; lt )j2 d

= 2t jF (f0 )(; nt )j2 + 2T t

(

j

?

1)

t

j =1 l=0

n=1

mX

?1 Z T

m

X

2

2t jF (f0 )(; nt )j + 2T t 0 jF (g )(; ; lt )j2 d:

n=1

l=0

X

(4.7)

Lemma 4.3 For any 2 C 1([0; T ]),

t

m

X

n=1

j(nt)j2 ?

T

Z

0

j(t)j2 dt 2 t

Z

0

T

j(t)j2 dt

1=2

1=2 Z T

0(t)j2 dt

j

:

0

(4.8)

Proof. We have, for some 0 m(t) t,

m

Z T

2

t j(nt)j = j(t + m(t))j2 dt:

0

n=1

X

Therefore,

m

Z T

2

2

t j(nt)j ? 0 j(t)j dt

=1

Z nZ

T m (t) @

2 ddt

= j

(

t

+

)

j

0 =0 @

Z T Z t

0 =0 2 j(t + )j j0(t + )j 1It+ T ddt

Z

1=2 Z

T

T 0 2 1=2

2

2 t 0 j(t)j dt

j (t)j dt :

0

(4.9)

X

(4.10)

We now come back to the proof of Theorem 4.1, and we use Lemma 4.3 in order to

compare the two Riemann sums of (4.7) with the corresponding integrals. We also use

13

the same inequality when the Riemann sum is taken from 0 to m ? 1. We get

t

m

X

n=1

T

j (nt; )j2

b

Z T Z T

2

2 0 jF (f0 )(; s)j ds + 2T 0 0 jF (g )(; ; s)j2 dsd

Z T

m

X

+ 2 t jF (f0 )(; nt )j2 ? jF (f0 )(; s)j2 ds

0

n=1 Z

Z

m

?

1

TZT

T

X

jF

(g )(; ; s)j2 dsd (4.11)

jF

(g )(; ; lt )j2 d ?

+ 2T t

0 0

l=0 0

Z

Z

Z

T

T

T

2 0 jF (f0 )(; s)j2 ds + 2T 0 0 jF (g )(; ; s)j2 dsd

Z

1=2

Z

T

T

2 ds 1=2

+ 4t

jF

(f0 )(; s)j2 ds jj

jr

F

(

f

)(

;

s

)

j

0

0 ZZ 0

1=2

1=2

Z Z

T T

2

2

jF (g )(; ; s)j dsd jj jrF (g )(; ; s)j dsd :

+4T t

0 0

Z

Using then Lemma 2.2, and proceeding as in Theorem 2.1, we obtain

t

m

X

n=1

CN;T

j (nt; )j2

b

1 + t k (v) (1 + jvj2)N=4+1=2k2

L (RNv)

jj

2 dv + T

j

f

(

;

v

)

j

0

N

(4.12)

1

Z

Z

b

v2R

Z

0

This yields the result by integration in .

v2RN

jg(; ; v)j2 dvd :

b

Remark 4.4 We have not been able to extend Theorem 4.1 to the case when

@tf + v rxf =

m

X

j =1

(t ? j t)

Z

j t

(j ?1)t

g(; x; v) + divv h(; x; v) d;

(4.13)

with g, h 2 L2(]0; T [RNx RNv ). We think that in this case, the conclusion of Theorem

4.1 (with kgk2L2 replaced by kf k2Lt (L2xv ) + kgk2L2 + khk2L2 , and smaller powers for 1=R

and t) might be false. The main reason is that an integral of the type

1

I () =

Z

0

T

j(tjj)j2 dt

(4.14)

obviously decays like 1=jj when 2 L2(R), whereas the discrete analogue satises

t

mX

?1

n=0

j(nt jj)j2 t j(0)j2;

(4.15)

and thus does not tend to 0 when jj ! 1. Therefore, it is not possible to estimate a

term containing such a sum multiplied by jj1=2.

14

5 Implicit methods

We now consider implicit methods for solving the free transport equation @tf +v rxf =

0. The distribution function f is approximated by f n at time nt (t > 0, n 2 N).

We treat the cases of the Euler implicit scheme

f n+1 ? f n + v r f n+1 = 0;

(5.1)

x

t

and of the second-order Crank-Nicolson scheme

f n+1 ? f n + v r f n + f n+1 = 0:

(5.2)

x

t

2

The initial datum f 0 is assumed to belong to L2(RNx RNv ). Then f n is uniformly

bounded in L2, kf n kL2(RNxRNv) kf 0kL2(RNxRNv). For any test function 2 Cc1(RNv ),

we dene the averages

n (x) =

Z

RN

f n (x; v) (v) dv 2 L2(RNx):

(5.3)

Theorem 5.1 For the Euler implicit scheme (5.1), n 2 H 1=2(RN ) for any n 1, and

for any s > (N ? 1)=2,

1

kn k2H_ 1=2(RN) CN;sk (v)(1 + jvj2)s=2k2L (RNv)kf 0k2L2(RNxRNv):

n=1

t

X

1

(5.4)

Theorem 5.2 For the Crank-Nicolson scheme (5.2), the following compactness esti-

mate for averages in time hold. For any R > 0,

Z

jj>R

t

m

X

n=0

n

bn ()

2

d C

t2A2 + AB

0 2

R kf kL2(RNxRNv);

(5.5)

where m 2 N, (n)0nm are arbitrary complex numbers, and

A=

mX

?1

n=0

jn ? n+1 j + jmj;

B = t

m

X

n=0

jnj

(5.6)

represent respectively the total variation and the L1 norm of .

Before proving these results, let us emphasize the big dierence between these

schemes. Using (5.1), we immediately see that for n 1, f n + t v rxf n 2 L2x;v .

Therefore, according to [7], n 2 Hx1=2. However, in general 0 2= H 1=2 (for example,

take for f 0 a tensor product). Then, in an estimate like (4.3) or (5.5), we only get a

term in 1=R (a term in t appears if the sum starts at n = 0).

15

For the Crank-Nicolson scheme (5.2), the situation is very dierent since there is

time reversibility, as in the continuous case (the L2 norm of f n is constant). When f 0

varies in L2, f n also varies in L2, and thus n only lies in L2x (for a given n). Compactness only occurs for averages in time, and we must have a term in t in (5.5). However,

the situation here is worse than in the continuous case, since we can only estimate an

average in time with respect to a smooth function (t) (of bounded variation), whereas

in the continuous case, an L2 function is enough.

Proof of Theorem 5.1. The solution f n+1 of (5.1) is given by

1

f n+1 (x; v) = e?sf n (x ? tsv; v) ds;

0

and we easily deduce that for any n 1,

Z

(5.7)

sn?1 f 0(x ? tsv; v) ds;

(n n??11)!

0

1

f n (; v) = e?s (ns? 1)! e?it s v f 0(; v) ds:

f n(x; v) =

1 ?s

e

Z

(5.8)

Z

b

b

0

Then, for a.e. 2 RN

n () =

Z

f n (; v) (v) dv

n?1

(5.9)

= e?s (ns? 1)! F (f 0 )(; ts) ds:

0

According to the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality,

1 ?s sn?1

1 ?s sn?1

n

2

j ()j 0 e (n ? 1)! ds 0 e (n ? 1)! jF (f 0 )(; ts)j2 ds;

(5.10)

and since the rst integral has value 1,

1

1 1 ?s sn?1

e (n ? 1)! jF (f 0 )(; ts)j2 ds

t jn ()j2 t

0

n=1

n=1

1

1

(5.11)

= jj jF (f 0 )(; z jj )j2 dz

0

CjN;sj v2RN jf 0(; v)j2 dv k (v)(1 + jvj2)s=2k2L (RNv)

by the same estimate as in Theorem 2.1. The result (5.4) follows by integration with

respect to the variable .

b

RN

Z 1

b

Z

Z

b

Z

X

!

X

b

Z

Z

b

1

Proof of Theorem 5.2. The solution f n+1 of (5.2) is given by

1

f n+1 (x; v) = 2 0 e?sf n (x ? 2t sv; v) ds ? f n (x; v);

t

f n+1 (; v) = 1 ? i 2t v f n (; v):

1+i 2 v

Z

b

b

16

(5.12)

Therefore, for any n 0

fbn (; v) =

and

1 ? i 2t v 1 + i 2t v n

!

f 0(; v);

(5.13)

b

Z

f n (; v) (v) dv

t v n

1

?

i

2

f 0(; v) (v) dv:

= N

R 1 + i 2t v Let us now introduce the angle 2] ? ; [ dened by

1 ? i 2t v = e?i ;

1 + i 2t v or equivalently = 2 Arctg( 2t v ). Then

n () =

b

RN

Z

b

(5.14)

!

b

t

m

X

n=0

nn () =

b

Z

'() = t

n=0

(5.16)

b

m

X

n=0

Using Abel's transform, we get

mX

?1

'()f 0(; v) (v) dv;

RN

'() = t

(5.15)

ne?in :

n

X

(n ? n+1)

l=0

e?il

tA j'()j j sin(

=2)j

(5.17)

+ tm

m

X

l=0

e?il ;

(5.18)

q

Now, since sin(=2) = 2t v = 1 + ( 2t v )2, we obtain

j'()j tA + jv2Aj (5.19)

But we can also use the trivial estimate j'()j B , and combined with (5.19) this

yields

j'()j tA + min jv2Aj ; B :

(5.20)

!

Now, coming back to (5.16) we get for a.e. 2 RN

t

m

X

n=0

n

bn ()

2

Z

jf 0(; v)j2 dv

Z

2j (v )j2 dv

RN

j

'

(

)

j

N

R

0

2

2 RN jf (; v)j dv t2A2 RN j (v)j2 dv

b

Z

Z

b

+

17

2 2A ; B j (v )j2 dv :

min

jv j

RN

Z

!

(5.21)

The last integral can be computed,

2A ; B j (v)j2 dv

jv j

RN

1

j

(u jj + v0)j2 dv0 du

min2 j2jjAuj ; B

=

v 2

u=?1

1

CN;sk (v)(1 + jvj2)s=2k2L (RNv) ?1 min2 j2jjAuj ; B du

= CN;sk (v)(1 + jvj2)s=2k2L (RNv) 8AB

jj Z

!

min2

!

Z

!

Z

0

?

(5.22)

!

Z

1

1

Finally, (5.21) gives for any s > (N ? 1)=2

t

m

X

n=0

n

bn ()

2

Z

2 RN

jf 0(; v)j2 dv

k k2L2(RN)t2A2

(5.23)

AB

2

s=

2

2

+CN;sk (v)(1 + jvj ) kL (RNv) jj ;

b

1

and (5.5) follows by integration in .

Remark 5.3 For the Crank-Nicolson scheme, the regularity of is really needed. There

is no inequality like (5.5) with the L2 norm in time instead of the average with respect

to . This can be seen by writing (5.14) as

n () =

b

Z

=?

e?in

Z

v 2

0

2

2

f 0 ; t2jj tan 2 jj + v0 dv0 1 +tan

tjj d:

d

?

(5.24)

Then by Parseval's formula

t

X

jbn ()j2

n2Z

= 2t

= 2

Z

Z

1

=?

Z

1 + tan2 2 2 d

2

0

0

0

f ; tjj tan 2 jj + v dv tjj

v 2

2 1 + ( t j ju)2

0

0

2

0

du;

f ; u jj + v dv

jj

Z

d

0

u=?1 v 2

0

?

d

?

and it is impossible to control the term in t2jj.

References

[1] M. Bezard, Regularite Lp precisee des moyennes dans les equations de transport,

Bull. Soc. Math. France, 122, (1994), 29{76.

[2] L. Desvillettes, S. Mischler, About the splitting algorithm for Boltzmann and

B.G.K. equations, Math. Mod. Meth. Appl. Sc., 6, (1996), 1079{1101.

18

[3] R.J. DiPerna, P.-L. Lions, Global weak solutions of Vlasov{Maxwell systems,

Comm. Pure Appl. Math., 42, (1989), 729{757.

[4] R.J. DiPerna, P.-L. Lions, Y. Meyer, Lp regularity of velocity averages, Ann. I.H.P.,

Analyse non{lineaire, 8, (1991), 271{287.

[5] P. Gerard, Microlocal defect measures, Comm. Partial Di. Eq., 16, (1991), 1761{

1794.

[6] F. Golse, Quelques resultats de moyennisation pour les equations aux derivees

partielles, Rend. Sem. Mat. Univ. Pol. Torino, Fascicolo Speciale 1988 "Hyperbolic

equations" (1987), 101-123.

[7] F. Golse, P.-L. Lions, B. Perthame, R. Sentis, Regularity of the moments of the

solution of a transport equation, J. Funct. Anal., 76, (1988), 110{125.

[8] F. Golse, B. Perthame, R. Sentis, Un resultat de compacite pour les equations de

transport et application au calcul de la limite de la valeur propre principale d'un

operateur de transport, C. R. Acad. Sc., Serie I, 301, (1985), 341{344.

[9] F. Golse, F. Poupaud, Limite uide des equations de Boltzmann des semiconducteurs pour une statistique de Fermi-Dirac, Asympt. Anal., 6, (1992), 135{

160.

[10] P.-L. Lions, Regularite optimale des moyennes en vitesses, C. R. Acad. Sc., Serie

I, 320, (1995), 911{915.

[11] P.-L. Lions, B. Perthame, Lemmes de moments, de moyenne et de dispersion, C.

R. Acad. Sc., Serie I, 314, (1992), 801{806.

[12] P.-L. Lions, B. Perthame, E. Tadmor, A kinetic formulation of multidimensional

scalar conservation laws and related equations, J. of the American Math. Soc., 7,

(1994), 169{191.

[13] B. Perthame, Higher moments for kinetic equations: the Vlasov-Poisson and

Fokker-Planck cases, Math. Methods in the Applied Sc., 13, (1990), 441{452.

[14] B. Perthame, P.E. Souganidis, A limiting case for velocity averaging, Ann. Scient.

Ecole Normale Superieure 4e serie, 31, (1998), 591{598.

[15] A. Vasseur, Convergence of a semi-discrete kinetic scheme for the system of isentropic gas dynamics with = 3, to appear in Indiana Univ. Math. J.

19